Table of Contents

Context: ASI will host a global conference in August to discuss decoding the script of the Indus Valley Civilization.

Indus Valley Civilization (IVC)

- Timeline: Existed from 3300 to 1300 BCE.

- Indus Valley Civilization spanned over 800,000 sq km across modern-day Pakistan and parts of northwestern India.

- It was discovered by John Marshall in 1924.

- Major sites: Harappa, Lothal, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi (largest site in the Indian Subcontinent), Kalibangan etc.

$1 Million Prize for Deciphering Indus Valley Script

Tamil Nadu Chief Minister has announced a $1 million prize for deciphering the script of the Indus Valley Civilisation.

About Indus Valley Script

- Indus Valley Script is a collection of symbols created by the Indus Valley Civilization. It is one of the oldest writing systems in the Indian subcontinent. It is also known as the Harappan Script.

- Script: Boustrophedon, is written right to left in one line and then left to right in the next line.

- Time Period: It was used from about 2,500 BC to about 1,900 BC.

- The earliest known writing system in the Indian subcontinent.

- Still undeciphered, presenting a major challenge to researchers.

- Language: It is unknown, and there are no known bilingual inscriptions to help decipher it.

- The script has been found on many objects, including pottery, seals, bronze and copper tablets, bronze tools, bones, and clay tablets.

- Symbols: About 400 symbols are known.

Features

- Inscribed on seals, pottery, tools, tablets, ornaments, etc.

- Written in pictorial and boustrophedon (alternate left-to-right and right-to-left) styles.

- Found on artefacts from Pakistan and northwest India.

- No inscriptions longer than 26 symbols.

Material Forms

- Inscribed on: Seals, pottery, bronze tools, stoneware, bones, shells, ivory, steatite, copper tablets.

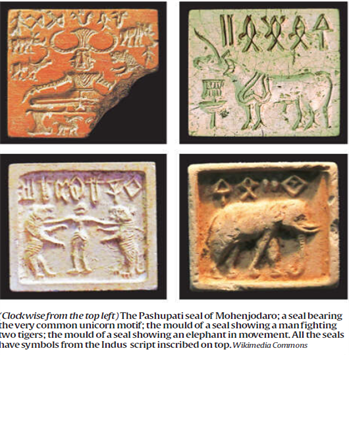

- Seals:

- Square, ~2.5 cm².

- Usually feature animal motifs with script on top.

- Made of steatite, silver, faience, calcite, often glazed.

- Functionality:

- Used for trade, identification, and administration.

- Some seals were used as amulets/talismans.

- Clay tags found in Mesopotamia show evidence of long-distance trade.

- Combined text + narrative imagery → possible religious or mythological significance.

Major Challenges in Deciphering the Indus Valley Script

- Lack of Multilingual Inscriptions

- Multilingual inscriptions are necessary for decipherment as they enable comparisons with known scripts.

- Despite robust trade links with Mesopotamia, no multilingual inscriptions from the Indus Valley have been found, unlike the Mesopotamian cuneiform script.

- Unknown Script and Language

- According to Andrew Robinson, undeciphered scripts fall into three categories:

- An unknown script is written in a known language.

- Known script writing in an unknown language.

- Unknown script writing in an unknown language (most challenging).

- The Indus script falls in the third category, with no certainty about the language it represents, making phonetic interpretation difficult.

- According to Andrew Robinson, undeciphered scripts fall into three categories:

- Limited Artefacts and Contextual Evidence

- Only 3,500 seals have been identified, each with an average of five characters.

- Insufficient material evidence makes analysis challenging compared.

- Many Indus sites remain undiscovered or underexplored, limiting insights into the civilisation’s context.

- Limited Knowledge of the Civilisation

- Compared to Mesopotamia and Egypt, far less is known about the social, cultural and economic systems of the Indus Valley Civilisation.

- Artefacts like the Pashupati Seal and seals with unicorn motifs provide clues but insufficient evidence.

- Archaeological Gaps

- Many sites may still be buried or uninvestigated.

- Greater archaeological efforts are needed to uncover material evidence for further research.

Indus Valley Cities and Sites: Important Findings

The urban centres of the Indus Valley Civilization had well-designed and organized infrastructure, architecture, and governmental structures.

The little Early Harappan villages had grown into huge cities by 2600 BCE. In modern Pakistan, these cities are Harappa, Ganeriwala, and Mohenjo-Daro; in contemporary India, these cities are Dholavira, Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Rupar, and Lothal. In total, more than 1,052 cities and settlements have been found, primarily near the Indus River and its tributaries. There may have once been five million people living in the Indus Valley Civilization.

| Site | Excavated by | Location | Important Findings |

| Harappa | Daya Ram Sahini in 1921 | Situated on the bank of river Ravi in Montgomery district of Punjab (Pakistan). |

|

| Mohenjodaro (Mound of Dead) | R.D Banerjee in 1922 | Situated on the Bank of river Indus in Larkana district of Punjab (Pakistan). |

|

| Sutkagendor | Stein in 1929 | In southwestern Balochistan province, Pakistan on Dast river |

|

| Chanhudaro | N.G Majumdar in 1931 | Sindh on the Indus river |

|

| Amri | N.G Majumdar in 1935 | On the bank of Indus river |

|

| Kalibangan | Ghose in 1953 | Rajasthan on the bank of Ghaggar river |

|

| Lothal | R.Rao in 1953 | Gujarat on Bhogva river near Gulf of Cambay |

|

| Surkotada | J.P Joshi in 1964 | Gujarat |

|

| Banawali | R.S Bisht in 1974 | Hisar district of Haryana |

|

| Dholavira | R.S Bisht in 1985 | Gujarat in the Rann of Kachchh |

|

Indus Valley Civilization: Phases

Early Harappan Phase From 3300 to 2600 BCE

The Early Harappan Phase, spanning 3300 to 2600 BCE, witnessed the emergence of settlements with rudimentary urban features in the Indus Valley. These early communities displayed initial signs of craftsmanship and trade.

Mature Harappan Phase From 2600 to 1900 BCE

The Mature Harappan Phase, lasting from 2600 to 1900 BCE, marked the apex of the Indus Valley Civilization. Flourishing cities, advanced urban planning, sophisticated trade networks, and intricate craftsmanship characterized this period.

Late Harappan Phase From 1900 to 1300 BCE

The Late Harappan Phase, spanning 1900 to 1300 BCE, saw a decline in urbanism and centralized authority in the Indus Valley. The disintegration of major cities, shifts in settlement patterns, and changes in trade routes marked this phase, signifying the civilization’s gradual decline.

Town Planning in Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization, flourishing from around 3300 to 1300 BCE, exhibited advanced town planning that reflected a high level of urban sophistication. Major cities such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa showcased meticulous urban layouts.

- Grid System: Cities were planned on a grid pattern with well-defined streets that intersected at right angles, indicating a remarkable sense of geometric planning.

- Citadel and Lower Towns: Cities often featured a citadel, elevated and fortified, alongside a lower town. The citadel housed important structures, possibly administrative or religious, while the lower town accommodated residential and commercial areas.

- Well-Planned Streets: Streets were wide and laid out in a north-south and east-west orientation. They were equipped with a sophisticated drainage system, including covered drains that ran beneath the streets.

- Brick Construction: Buildings were constructed using standardized, kiln-fired bricks, showcasing uniformity in size and shape. This standardization suggests centralized planning and construction methods.

- Residential Structures: Houses were typically two or more stories high, with rooms arranged around a central courtyard. They often included features like private wells and bathing areas, emphasizing a focus on hygiene.

- Great Bath: In Mohenjo-daro, the Great Bath is a significant structure believed to have had ritualistic or religious importance. It had a sophisticated water drainage system, showcasing engineering prowess.

- Public Buildings: Cities had public structures, possibly assembly halls or marketplaces, indicating a level of central authority and organized civic life.

- Trade and Commerce: The presence of granaries and warehouses suggests organized economic activities, with evidence of trade networks extending to Mesopotamia.

Despite the advancements in town planning, many aspects of the Indus Valley Civilization remain enigmatic, as the script used by its inhabitants remains undeciphered, limiting our understanding of their governance and societal structure.

Great Bath of Indus Valley Civilization

The “first public water tank in the ancient world” is another name for Mohenjo-Great Daro’s Bath. Mostly and exclusively utilised for religious rituals, the Great Bath was also occasionally used for bathing. There is no indication of a temple around, therefore they may have utilized this for religious rituals. Due to their poverty or perceived lack of purity, some people were not even permitted to attend the Great Bath.

The Great Bath, one of the most important Indus cultural centres, is a part of a massive citadel complex that was unearthed at Mohenjo-Daro during excavations in the 1920s. A thick layer of natural tar, also known as bitumen, which is utilized to hold water, and fine baked waterproof mud bricks are used to construct the huge bath. A large, rectangular tank encircled on all sides by hallways, with flights of stairs leading into the tank on the north and south.

Indus Valley Civilization: Society & Political System

- Regarding a centre of power or representations of the powerful in Harappan civilization, archaeological evidence do not immediately offer any answers. Pottery, seals, weights, and bricks with regulated sizes and weights are among the artefacts of the Harappan culture that exhibit an amazing degree of consistency, indicating some kind of authority or system of government. Regarding the Harappan system of rule or governance, three significant hypotheses have emerged over time.

- The first is that, given the uniformity of the artefacts, the indication of planned colonies, the standardization of brick size, and the apparent placement of towns close to raw material sources, there was a single state that included all the communities of the civilization.

- According to the second theory, each of the urban centres, including Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa, and other settlements, had a number of rulers who represented them. Finally, researchers have proposed that there were no rulers in the Indus Valley Civilization in the traditional sense of the word; instead, everyone lived in equality.

Agriculture in Indus Valley Civilization

- Food grain production was adequate in the Harappan communities, which were primarily located close to the river plains. It was possible to grow wheat, barley, rai, peas, sesame, lentil, chickpea, and mustard. Additionally, Gujarati places have millets. While rice was only occasionally used.

- Cotton was first produced by the Indus civilization. Grain findings suggest the presence of agriculture, but it is more challenging to recreate actual agricultural operations.

- Bulls have been depicted on seals and in clay art and extrapolation by archaeologists suggest that oxen were also utilized for ploughing. The majority of Harappan sites are found in semi-arid regions, where irrigation was probably necessary for farming. Canal remnants have been discovered at the Afghani Harappan site at Shortughai, but not in Punjab or Sindh. Despite engaging in agriculture, the Harappans also raised animals on a massive scale.

- Mohenjodaro’s surface level and a dubious ceramic statue from Lothal both include evidence of the horse. In any event, horses were not central to the Harappan civilization.

Indus Valley Civilization: Technology

- The Indus Valley inhabitants made numerous important technological advancements, including very accurate systems and tools for measuring length and mass.

- One of the first civilizations to create a system of standard weights and measurements that followed a scale was Harappa. On an ivory scale that was discovered at Lothal, a significant Indus Valley city in the contemporary Indian state of Gujarat, the smallest division, measuring roughly 1.6 mm, was written. It is the tiniest division of a Bronze Age scale that has ever been identified. The regular size of the bricks used to construct the Indus towns is another sign of an advanced measurement system.

- Dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick platforms, and defense walls built by the Harappans served as examples of sophisticated building. The sewer and drainage systems utilized in ancient Indus cities were far more sophisticated and effective than any seen in modern-day Middle Eastern cities, and they are being used in many parts of Pakistan and India today.

- It was thought that the Harappans were skilled carvers of patterns into the underside of seals. To mark their properties and impress clay on trade products, they used several seals. A seal decorated with elephant, tiger, and water buffalo patterns has been one of the objects discovered in Indus Valley towns the most frequently.

- The Harappans also executed elaborate handicrafts employing items made of the semi-precious gemstone, Carnelian, and created new methods for working with metallurgy, the science of working with copper, bronze, lead, and tin.

Indus Valley Civilization: Art and Culture

- Many different works of art from the Indus Valley culture have been discovered at excavation sites, including sculptures, seals, ceramics, gold jewellery, and anatomically accurate figurines made of terracotta, bronze, and soapstone.

- One of the many figurines made of gold, terracotta, and stone depicted a “Priest-King” with a beard and patterned robe. Another bronze figurine, the “Dancing Girl,” stands just 11 cm tall and depicts a female figure in a stance that might indicate the existence of a choreographed dance style that was practised by people in the civilization.

- There were also terracotta works of cows, bears, monkeys, and dogs. In addition to figurines, it is thought that the inhabitants of the Indus River Valley also produced necklaces, bangles, and other decorations.

Indus Valley Civilization: Crafts

- The largest of the four ancient civilizations—which also included Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China—the Indus Valley Civilization is the earliest known example of the type of culture on the Indian subcontinent that is generally referred to as “urban” (or focused on large communities).

- It has been determined that the Indus River Valley’s civilization existed during the Bronze Age, or roughly 3300–1300 BCE. It was situated in what is now Pakistan and India, and it encompassed a region the size of Western Europe.

- The two most important towns of the Indus Valley Civilization, Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, appeared in the Sindh and Punjab provinces of Pakistan approximately 2600 BCE along the Indus River Valley.

- Important archaeological information about the civilization’s technology, art, trade, transportation, writing, and religion was uncovered and uncovered during their discovery and excavation in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Indus Valley Civilization: Religion

- The religion of Harappa is still up for debate. There is widespread speculation that the Harappans revered a mother deity who represented fertility.

- Indus Valley Civilization appears to have lacked any temples or palaces that would have provided indisputable proof of religious rites or particular deities, in contrast to Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations. A swastika emblem, used in later Indian religions including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, is depicted on some Indus Valley seals.

- Numerous Indus Valley seals also feature animal forms; some represent animals being carried in processions, while others show chimaera creations. This has led academics to theories about the significance of animals in Indus Valley religions. One Mohenjo-Daro seal depicts a tiger being attacked by a half-human, half-buffalo creature.

- This may be a reference to the Sumerian narrative about a monster that Aruru—the goddess of the ground and fertility in that culture—created to battle Gilgamesh, the protagonist of an old Mesopotamian epic poem. This is yet another indication of Harappan culture being traded internationally.

Trade & Economy during Indus Valley Civilization

Harappan city workshops utilized raw materials imported from Iran and Afghanistan, as well as lead and copper from other regions of India, jade from China, and cedar wood that had been carried down rivers from the Himalayas and Kashmir. Trade was centered on acquiring these resources. Terracotta pots, gold, silver, metals, beads, flints for creating tools, seashells, pearls, and colored gemstones like lapis lazuli and turquoise were among the additional trade items.

The Harappan and Mesopotamian civilizations had a robust maritime trading network in place. At archaeological sites in Mesopotamia, which covers the majority of contemporary Iraq, Kuwait, and parts of Syria, Harappan seals and jewellery have been discovered. The creation of plank boats with a single central mast bearing a sail made of woven rushes or fabric may have made long-distance sea trade over waterways like the Arabian Sea, Red Sea, and Persian Gulf possible.

The presence of multiple seals, standardized writing, and standardized weights and measures throughout a large area attests to the significance of trade in the lives of the Indus people. The Harappans engaged in extensive trading in goods including shells, metal, and stone. Trade was conducted using the barter system rather than metal money. On the Arabian Sea’s coast, they practised navigation. In the north of Afghanistan, they had established a commercial colony that, presumably, enabled trade with Central Asia.

Additionally, they conducted business with people living in the Tigris and Euphrates region. The long-distance lapis lazuli trade that the Harappans engaged in may have boosted the social standing of the governing class.

Decline Indus Valley Civilization

Although the precise causes of the Indus Valley Civilization’s decline are still up for debate, it happened approximately 1800 BCE. According to one version, the Indus Valley Civilization was invaded and subjugated by the Indo-European tribe known as the Aryans. Different pieces of the Indus Valley Civilization have been discovered in later societies, suggesting that civilization did not abruptly end owing to an invasion.

On the other side, a lot of academics think that the fall of the Indus Valley Civilization was caused by natural reasons:

- Geological and climatic elements may constitute the natural factors.

- It is thought that the Indus Valley region had a number of tectonic disturbances that resulted in earthquakes and altered the paths of rivers or caused them to dry up.

- Changes in rainfall patterns could be another natural cause.

There could also be dramatic shifts in the river courses, which might have brought floods to the food-producing areas. Due to a combination of these natural causes, there was a slow but inevitable collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization.

Nagari Pracharini Sabha Revival: Backgro...

Nagari Pracharini Sabha Revival: Backgro...

Ryotwari System in India, Features, Impa...

Ryotwari System in India, Features, Impa...

Battle of Plassey, History, Causes, Impa...

Battle of Plassey, History, Causes, Impa...