Table of Contents

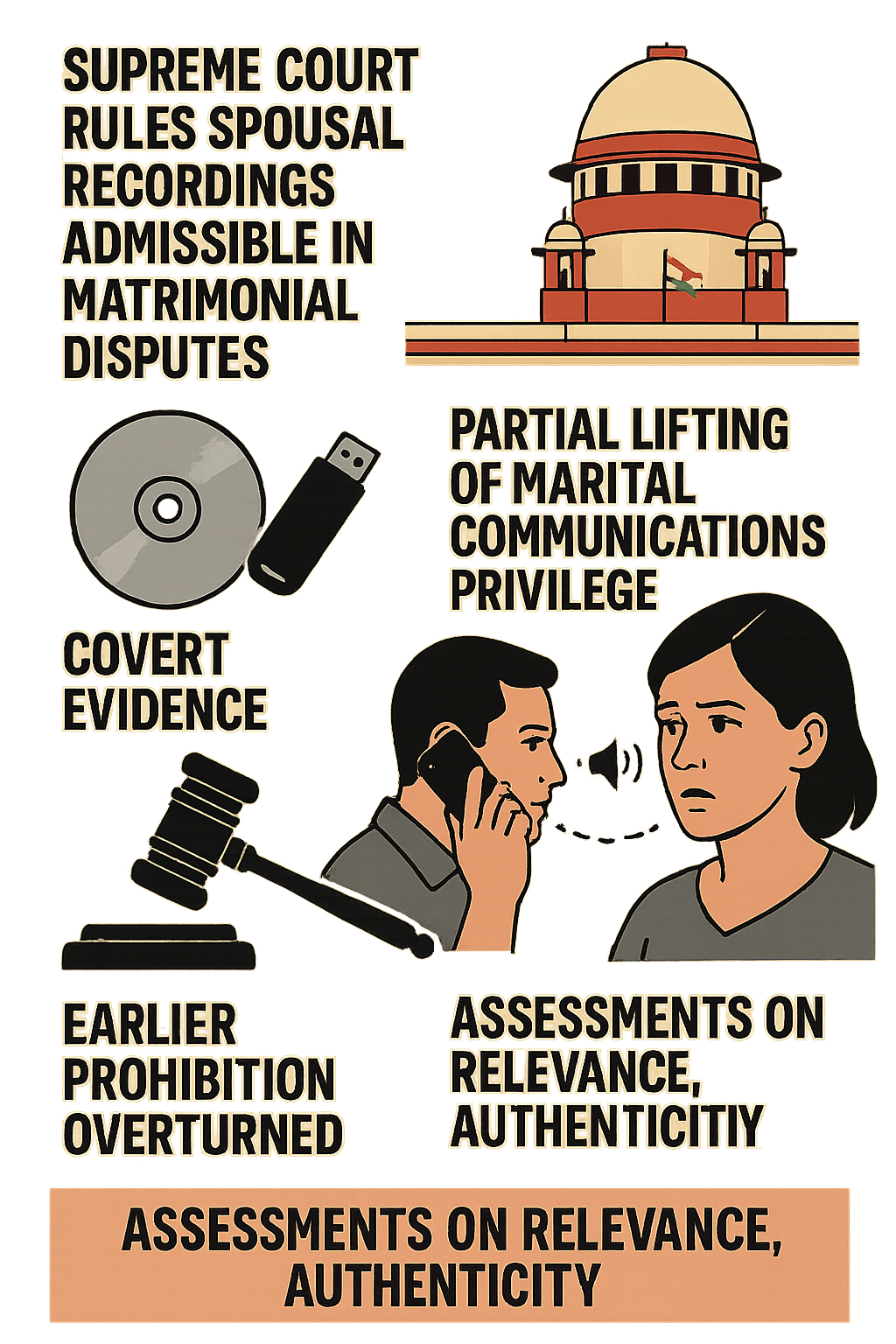

On Monday, the Supreme Court ruled that conversations secretly recorded by one spouse can be admitted as evidence in matrimonial disputes, including divorce proceedings. This decision overturns the earlier prohibition on such recordings and marks the first time the apex court has squarely addressed the admissibility of covert electronic evidence in family law.

Previous SC Judgement on Spousal Conversations in Matrimonial Cases

The bench set aside a 2021 judgment of the Punjab and Haryana High Court, which had barred a husband from relying on secretly recorded telephone conversations with his wife to support his cruelty petition. By restoring the trial court’s order, the Supreme Court allowed the husband to produce compact discs and digital storage devices containing these recordings, subject to verification of authenticity and compliance with evidentiary standards.

Traditionally, Section 122 of the Indian Evidence Act protected private marital communications from disclosure, even post-marriage. The Supreme Court’s ruling clarifies that this protection is not absolute in matrimonial suits: where relevant, independently verifiable recordings may be admitted under the very exception carved out by the same provision for suits between married persons.

This judgment recalibrates the balance between the right to privacy and the right to a fair trial. It signals that technological evidence from phone taps to voice recordings cannot be excluded solely because it was obtained in secret. Going forward, family courts will have to assess covert recordings on criteria of relevance, authenticity, and reliability rather than dismiss them outright.

Vibhor Garg v. Neha SLP(C) No. 21195/2021: Recent Matrimonial Case

On July 14, the Supreme Court overturned a Punjab & Haryana High Court decision, allowing undisclosed recordings of phone conversations between spouses to be admissible as evidence in family court. Justices B.V. Nagarathna and Satish Chandra Sharma stated that while Section 122 of the Indian Evidence Act protects marital communications, it includes exceptions for legal disputes between spouses.

The Court emphasised that privacy rights under Section 122 are not absolute and must be balanced with the right to a fair trial. They dismissed concerns that such recordings might harm domestic harmony, noting that secret monitoring indicates underlying trust issues that courts must address.

Background

In a divorce case under Section 13 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, Justice Lisa Gill of the Punjab & Haryana High Court delivered a significant ruling. The dispute arose when the Family Court in Bathinda permitted the husband to submit a compact disc containing secretly recorded phone conversations with his wife, aiming to substantiate his allegations of cruelty.

The wife contested this decision before the High Court, arguing that the recordings were made without her knowledge or consent, thereby violating her fundamental right to privacy under Article 21 of the Constitution. She contended that admitting such evidence would set a dangerous precedent, encouraging covert surveillance within marriages.

The High Court agreed with her position and overturned the Family Court’s order. It emphasised that the recordings were obtained surreptitiously, and the context in which the wife’s responses were elicited could not be reliably determined—even through cross-examination. The Court observed that it cannot be said or ascertained as to the circumstances in which the conversations were held or how response was elicited by a person who was recording the conversations, because it is evident that these conversations would necessarily have been recorded surreptitiously by one of the parties.”

To reinforce its reasoning, the High Court cited Deepinder Singh Mann v. Ranjit Kaur, where it was held that spouses often speak candidly in private, unaware that their words might later be dissected in court. It also relied on Smt. Rayala M. Bhuvaneswari v. Napaphander Rayala, a landmark judgment from the Andhra Pradesh High Court, which declared that recording a spouse’s conversation without consent is unlawful and constitutes a breach of privacy, rendering such evidence inadmissible.

In response, the husband escalated the matter to the Supreme Court via a Special Leave Petition (SLP). On January 12, 2022, a bench comprising Justices Vineet Saran and B.V. Nagarathna issued notice in the case.

Representing the husband, Advocate-on-Record Ankit Swarup argued that the right to privacy is not absolute and must be weighed against competing rights, particularly the right to a fair trial. He invoked the exception under Section 122 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, which allows disclosure of marital communications in legal proceedings between spouses.

The petition elaborated that in cases involving mental cruelty, the incidents often occur in private spaces such as the matrimonial home or bedroom where no third-party witnesses are present. In such scenarios, technological tools like audio recordings may be the only viable means to recreate and present evidence before the court. However, the petition also acknowledged the need for judicial caution, urging courts to verify the authenticity and reliability of such electronic evidence before relying on it.

Additionally, the husband cited Sections 14 and 20 of the Family Courts Act, 1984, which empower Family Courts to adopt flexible evidentiary standards and prioritize the discovery of truth over rigid procedural constraints. He argued that the recorded conversations were not just relevant but essential to prove the cruelty alleged, and without them, he would be unable to secure a divorce decree.

Spousal Privilege

Spousal privilege is a legal concept designed to protect the confidentiality of communications between married partners, ensuring that one spouse cannot be compelled to testify against the other in criminal proceedings. This principle is rooted in the belief that marital trust should receive special legal protection.

Under Section 122 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, it is outlined that no individual who is or has been married can be forced to disclose any communication made to them during their marriage. This statutory provision underscores the importance of safeguarding private dialogues exchanged between spouses, reflecting society’s recognition of the sanctity of the marriage bond.

The scope of spousal privilege encompasses all confidential discussions that occur between spouses during their marriage. However, there are notable exceptions to this rule. If the spouse from whom testimony is sought provides explicit consent, that communication may be admissible as evidence in court. Similarly, if a spouse shares details of a private marital conversation with a third party, the privilege may be waived, and that third party can be called to testify about the disclosed information.

The practical implications of spousal privilege are significant. By allowing spouses to communicate freely without the fear that their words could be used against them in criminal trials, it reinforces the sanctity of private marital discourse. While it protects individuals’ privacy, it also balances this with the needs of justice by permitting the introduction of evidence if both parties agree or if confidentiality is breached through the involvement of an outside witness.

It is also essential to consider related aspects of spousal privilege. For instance, it is distinct from the witness incompetency rule, which may prevent a spouse from testifying altogether in certain jurisdictions. Additionally, spousal privilege continues to exist even after a divorce; communications made during the marriage remain protected despite the dissolution of the marital relationship.

In cases where both spouses are co-accused in a joint criminal case, the application of spousal privilege can become complex, and courts typically assess the validity of the privilege on a case-by-case basis. Overall, spousal privilege serves a crucial role in preserving the integrity of marital communications while navigating the legal frameworks of justice.

Judiciary weighs covert recordings against constitutional rights and evidentiary relevance in divorce litigation.

When spouses part ways in divorce proceedings, the usual rule that protects private communications between them spousal privilege, no longer shields one from having to testify against the other. When one spouse levels charges, their testimony enters the record alongside corroborating materials: traditional items like personal letters, photos, and third-party statements, and, increasingly, digital traces such as text messages, voice or video recordings, and emails.

High Courts have generally balked at admitting covert audio or video captures, citing two core concerns. First, recordings made without consent can involve dubious or heavy-handed methods of collection. Judges must sift through each piece of material to see whether it genuinely bears on the issues and was gathered in a legally acceptable way a process known as appreciation of evidence. Second, clandestine recordings breach the reasonable expectation of privacy spouses enjoy, transforming intimate domestic life into a realm of unwelcome surveillance.

Yet India’s Supreme Court has recently signalled a shift. It drew on a 1973 precedent in which secretly tapped telephone conversations helped secure a corruption conviction against a public official. At that time, the court overlooked how the state-authorised tap was arranged, focusing instead on the importance of the evidence itself. That same logic now extends to private marital disputes: if secretly recorded material is directly relevant, capable of independent verification, and aligns with statutory exceptions on admissibility, it may be received in court despite its furtive origins.

In reaching this conclusion, the Supreme Court has stressed the need to reconcile two fundamental rights, i.e., the right to privacy and the right to a fair trial. While acknowledging that secret recordings intrude upon personal privacy, the justices likened a recording device to an “eavesdropper” who overhears a privileged conversation. If that eavesdropper’s testimony illuminates the truth and fits within the legal framework, it can be admitted much like the testimony of any witness.

This decision has far-reaching implications for how marital privacy and marital trust are balanced. In interpreting Section 122 of the Evidence Act, the court underscored that the provision was meant to uphold the sanctity of marriage, not to freeze spousal confidentiality in the face of serious allegations. At the same time, the Supreme Court’s landmark 2017 judgment in Puttaswamy enshrined privacy as a fundamental right, meaning any encroachment must rest on a valid legal foundation.

Critics worry that sanctioning secret recordings within divorce battles may fuel a climate of constant monitoring between spouses. The Supreme Court, however, observed that such surreptitious surveillance often signals a relationship already bereft of trust. Another concern is the stark gender gap in smartphone ownership: with women less likely to possess recording-capable devices, men could enjoy a decisive advantage when gathering evidence in matrimonial disputes.

By threading the needle between privacy and probative value, the Supreme Court has pivoted the law towards a more evidence-centric approach in divorce litigation one that eggs on litigants to produce proof, secret or otherwise, as long as it is relevant, verifiable, and statutorily permissible.

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...