Table of Contents

Why in the news?

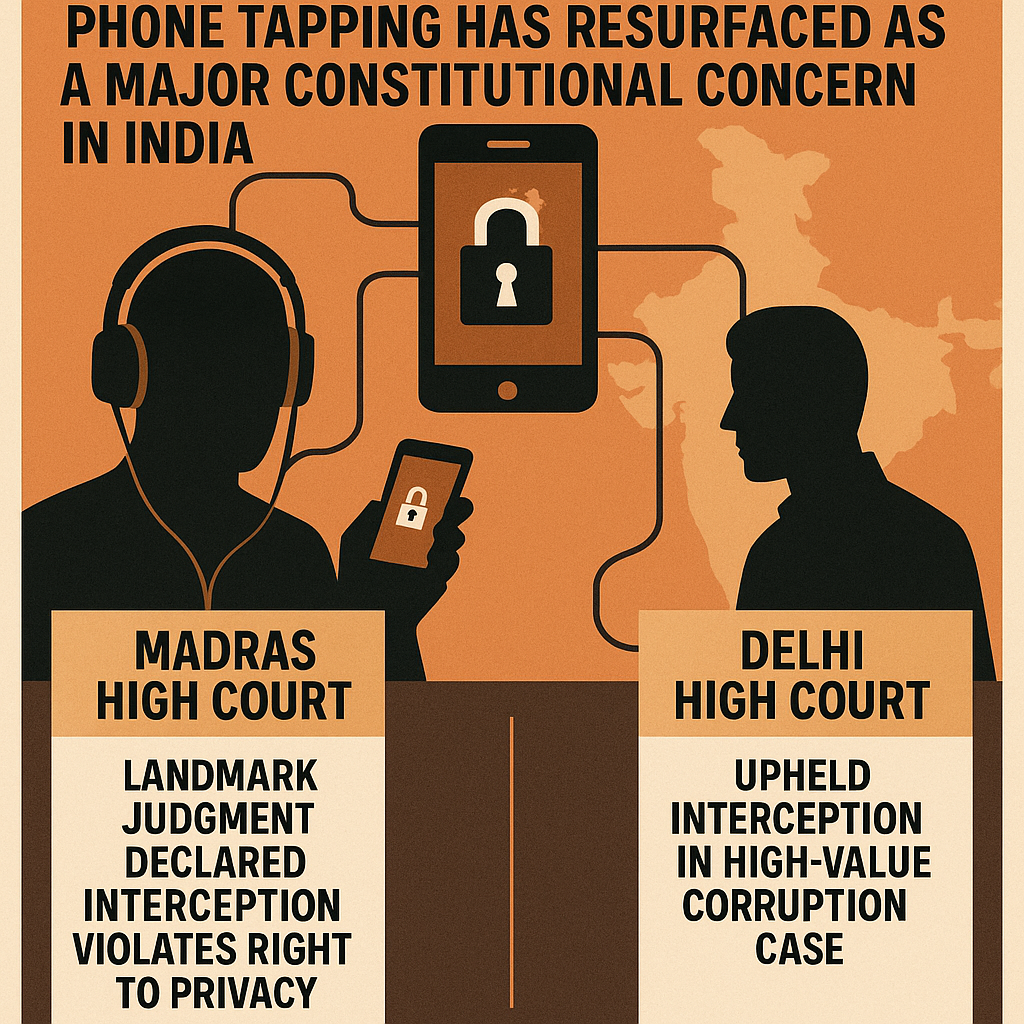

In 2025, the issue of government-authorised phone tapping resurfaced as a major constitutional concern in India. This renewed scrutiny stems from two divergent High Court rulings by the Madras High Court and the Delhi High Court, which have sparked national debate over the legality of intercepting private communications before any crime has occurred.

Madras High Court has stated in a landmark judgment, the court ruled that phone interception cannot be justified solely for detecting ordinary crimes, such as bribery or tax evasion, unless there is a public emergency or a threat to public safety. It emphasised that covert surveillance violates the fundamental right to privacy under Article 21 unless backed by strict legal safeguards and procedural compliance.

In contrast, the Delhi High Court upheld interception in a high-value corruption case, arguing that the economic scale of the offence posed a serious threat to public safety and governance. It interpreted “public safety” broadly to include large-scale financial crimes, thereby validating pre-crime surveillance under Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885.

These conflicting decisions underscore the legal and ethical tension between the state’s duty to maintain security and the citizen’s right to privacy. They also highlight the evolving judicial interpretations of surveillance laws, especially in light of the Telecommunications Act, 2023, which carries forward older provisions but defers key safeguards to future rule-making.

Legal Framework for Government-Sanctioned Phone Tapping in India

The legal framework for government-sanctioned phone tapping in India is primarily built on three significant statutes, each intertwined with constitutional safeguards that regulate the interception of private communications. The Indian Telegraph Act of 1885 was originally enacted to manage telegrams, but its scope was later expanded through judicial interpretation and executive notification to encompass telephone calls. Section 5(2) of this act empowers the central or state government to intercept messages only in situations deemed as a “public emergency” or where there is a threat to “public safety.”

Alongside this, the Indian Post Office Act of 1898 governs postal and courier services and includes provisions for the interception of letters and parcels under circumstances similar to those outlined in the Telegraph Act. While this act is less frequently invoked concerning phone calls, it reinforces the notion that private correspondence may be subject to official surveillance but only under narrowly defined conditions.

The Information Technology Act of 2000 further addresses the interception, monitoring, and decryption of electronic data, including voice-over-IP calls and text messages. Under Section 69, this legislation grants the government the authority to order interception for reasons resembling those of the Telegraph Act—namely, sovereignty, security, public order, and the prevention of crime.

A vital constitutional check comes from Article 19(2) of the Constitution, stipulating that any restriction on free speech or privacy through these laws must meet the “reasonable restrictions” test. Valid grounds for such restrictions include the sovereignty and integrity of India, security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, and preventing incitement to an offence. Surveillance measures are mandated to be proportionate, prescribed by law, and subject to periodic review to ensure that they do not infringe upon fundamental rights.

In terms of authorisation and oversight, only the Union Home Secretary or the respective State Home Secretary, or an officer designated by them, can sanction interception orders. The initial approval for such interception usually lasts up to 30 days, with extensions permitted only after a fresh review of necessity. Furthermore, every interception order and its justification must be thoroughly logged and subjected to periodic audits by an oversight authority to prevent any potential misuse.

When examining these provisions, a comparative snapshot reveals how these statutes interact with each other. The Indian Telegraph Act, enacted in 1885, encompasses telegrams and telephone calls under Section 5(2), allowing interception during public emergencies or for public safety reasons. Similarly, the Indian Post Office Act of 1898 covers postal and courier communications under Section 7, with similar grounds for interception. Meanwhile, the Information Technology Act of 2000 extends its scope to electronic data, VOIP, and SMS under Section 69, justified by concerns for sovereignty, security, public order, and crime prevention.

This intricate matrix of laws ensures that the executive power to monitor communications is tightly bound by procedural checks and constitutional norms, with the overarching aim of making the interception of a citizen’s private messages an extraordinary measure rather than a routine practice.

High Court Rulings on Pre-Crime Phone Interception

In 2025, two High Courts delivered contrasting judgments concerning the legality of state interception of phone conversations before any crime has occurred. These rulings not only highlight the legal complexities surrounding preemptive surveillance but also reflect the ongoing struggle to find an appropriate balance between proactive law enforcement and the fundamental right to privacy.

Delhi High Court Ruling

The Delhi High Court evaluated a significant corruption investigation linked to a government contract valued at over ₹2,000 crore. In its ruling, the court recognised that the staggering financial implications of this offence posed a serious threat to both public safety and effective governance.

By underscoring the extensive repercussions of corruption on the economy, administrative integrity, and the trust of citizens, the court affirmed that preemptive interception of communications was justified under Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act. This decision underscores the court’s stance that maintaining public order and safety can sometimes necessitate infringing on individual privacy rights, especially in cases involving high-stakes financial misconduct.

Madras High Court Ruling

Conversely, the Madras High Court approached a different case involving allegations of bribery and tax evasion totaling around ₹50 lakh. In this instance, the court struck down the interception order, concluding that routine tax fraud, despite being illegal, did not rise to the level of a “public emergency” or significantly threaten public safety as defined by law.

The court’s judgment also emphasised procedural inadequacies in the government’s sanctioning process, reinforcing the necessity for rigorous compliance with statutory safeguards to protect individual rights. This ruling illustrates a more cautious and restrained interpretation of preemptive surveillance, prioritising the enforcement of procedural norms over broad assertions of public safety.

Together, these rulings illustrate a judicial divide on the subject of preemptive surveillance. The Delhi High Court adopts a broad, impact-oriented view of threats where significant economic offences warrant greater scrutiny and intervention.

In contrast, the Madras High Court maintains a narrow, procedural interpretation, emphasising the necessity of clear criteria for what constitutes a “public emergency.” This divergence not only shapes the legal landscape surrounding surveillance but also sparks a broader dialogue about the implications for privacy rights in an era where public safety and crime prevention are paramount concerns.

Constitutional Safeguards and Procedural Norms: A Closer Look

In 1997, the Supreme Court delivered a landmark judgment in People’s Union of Civil Liberties vs Union of India that laid down a rigorous framework for government interception of private communications. The Court recognised the tension between state security needs and citizens’ right to privacy and free speech. By prescribing clear procedural steps, it sought to ensure that any order for telephone or telegraphic tapping would not be arbitrary or open to abuse.

Stringent Authorization Requirements

Only the Home Secretary, either at the state or the central level, has the legal authority to approve any interception request. This concentration of power at a very senior rank guarantees political accountability for decisions that intrude on personal privacy.

Non-Delegable Authority

The Supreme Court emphasised that this authorising power cannot be passed down to officials ranked below a Joint Secretary. In practice, this means no undersecretary or deputy secretary can green-light tapping orders, preserving a high threshold of senior-level scrutiny.

Mandate of Necessity Verification

Before signing off on any interception, the Home Secretary must be satisfied that:

- The intelligence sought cannot be obtained by alternative, less invasive methods.

- Surveillance is strictly confined to the scope and duration essential for that purpose.

This “last resort” principle ensures that tapping is used sparingly and only when it is genuinely indispensable.

Structured Review Mechanism

To guard against prolonged or unwarranted surveillance, the ruling requires a periodic assessment by a specially constituted review committee. Within two months of the interception order:

- A panel headed by the Cabinet Secretary at the centre (or the Chief Secretary in a state)

- Includes senior officials from the Home and Law Departments

- Examines the legality and continued necessity of the tapping

If the committee finds deficiencies or a lack of justification, it can recommend revocation of the order.

Protecting Fundamental Rights

Together, these safeguards create a multi-tiered check on executive power. By demanding senior-level sign-off, a clear demonstration of necessity, and regular independent review, the Supreme Court’s framework aims to shield citizens from arbitrary state intrusion and uphold their constitutional liberties.

Divergent High Court Interpretations

Two recent High Court decisions illustrate the fundamental tension between safeguarding personal privacy and advancing national security objectives. The Delhi High Court adopted a broad interpretation of “public safety,” extending it to cover significant economic offences.

In contrast, the Madras High Court insisted on a tighter reading, requiring that any surveillance strictly comply with existing statutory and procedural safeguards. These conflicting views shape the legal boundaries within which interception powers can operate.

Delhi’s Broader Public Safety Doctrine

The Delhi ruling expands the concept of public safety to include crimes that threaten economic stability on a large scale. Under this view, serious financial fraud or systemic market manipulation could justify government-authorised tapping, even before a crime is committed. By treating economic offences as potential threats to society’s well-being, the decision opens the door for more proactive intervention in the interest of public order.

Key takeaways:

- Economic offences classified as “public safety” concerns

- Allows pre-emptive surveillance to disrupt complex financial crimes

- Lowers the threshold for invoking interception in non-violent but socially disruptive offences

Madras’s Procedural Rigidity

The Madras High Court’s approach pulls in the opposite direction, insisting that privacy safeguards are not to be diluted for vague notions of security. It emphasised that interception orders must follow the letter of the law, with stringent adherence to eligibility criteria, authorisation hierarchy, and necessity checks. Any deviation or extension beyond clearly defined offences risks invalidating the entire surveillance process.

Key takeaways:

- Rejects expansion of “public safety” beyond explicitly listed threats

- Upholds strict compliance with procedural norms laid down by statute and precedent

- Protects against broad or anticipatory use of interception powers

Pre-emptive Interception: A Legal Frontier

These divergent rulings directly impact the question of whether authorities can tap communications before an offence is fully formed. The Delhi approach legitimises pre-emptive monitoring when there is credible evidence of looming large-scale economic crime. The Madras stance, however, would reserve interception for situations in which the offence has materialised or is imminent within the narrowly defined categories.

Going forward, these contrasting judgments will influence both policymaking and judicial review of interception orders. Legislators may feel pressure to clarify or amend the law to settle the scope of “public safety.” Courts, meanwhile, will likely grapple with reconciling competing interests, balancing the state’s duty to prevent harm against the individual’s right to secrecy of communication. This evolving landscape will define the permissible reach of surveillance in an era where technology makes pre-emptive intervention ever more feasible.

A Choice Before India: Rule of Law or Ru...

A Choice Before India: Rule of Law or Ru...

The Right to Speedy Trial Under Article ...

The Right to Speedy Trial Under Article ...

Making Forest Conservation Work for Fore...

Making Forest Conservation Work for Fore...