Table of Contents

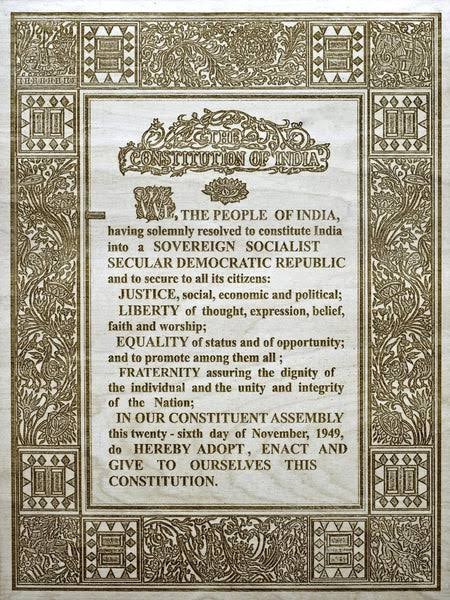

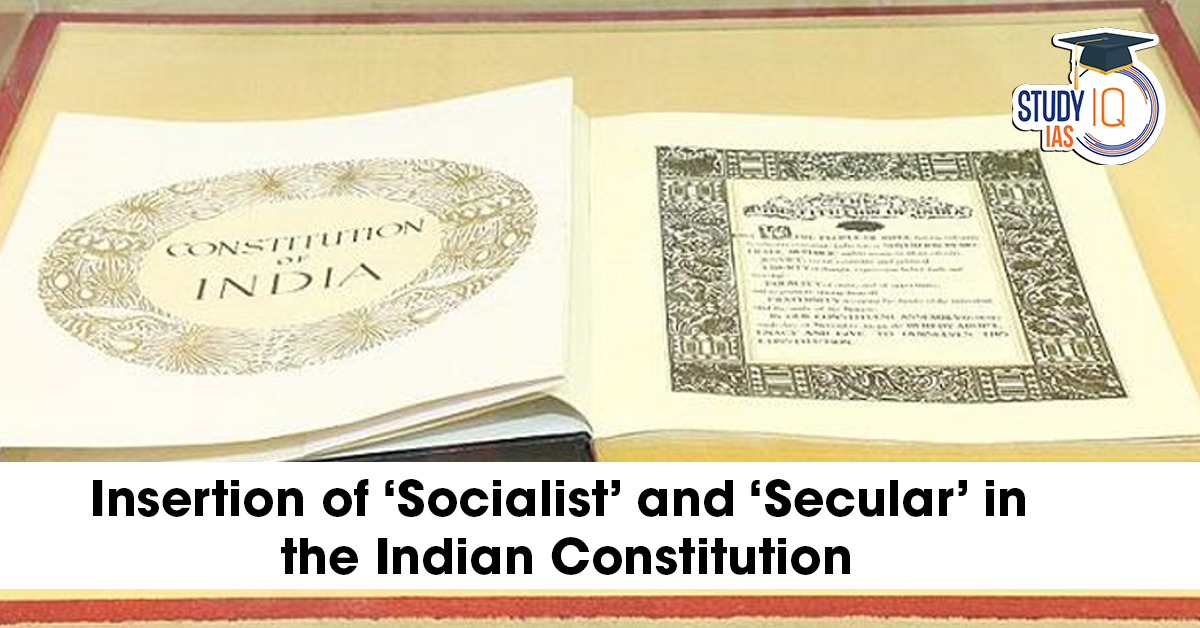

Since its adoption in 1950, the Indian Constitution has functioned as a dynamic text, capable of adapting to the evolving political, social, and economic requirements of the nation. One of the most controversial constitutional modifications occurred during the Emergency period when the 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act of 1976 incorporated the terms “socialist” and “secular” into the Preamble.

The evolution of India’s self-conception as a “sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic” persists in provoking political, intellectual, and legal discourse. Critics condemn the context and technique of insertion, while defenders argue that the language embodies principles already ingrained in the constitutional framework.

Historical Context: The Emergency and the 42nd Amendment

- The Emergency (1975–1977), proclaimed under Article 352 by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, was characterised by the suspension of civil liberties, censorship of the press, and widespread arrests.

- During this era of centralised authoritarianism, the 42nd Amendment, commonly known as the “Mini-Constitution”, was enacted, substantially modifying the power dynamics between the administration and the judiciary, augmenting the Directive Principles, and revising the Preamble.

- Significant Enhancements to the Preamble:

a. “Socialist”

b. “Secular”

c. “Integrity of the Nation”

- These additions, particularly under undemocratic conditions, epitomised the overextension of governmental authority.

The Ideological Intent: Socialist and Secular

Socialist

- The term “socialist“ emphasised the Indira Gandhi administration’s populist and redistributive goal, reflected in slogans such as Garibi Hatao and policies such as bank nationalisation, the abolition of privy purses, and the enhancement of state welfare systems.

- This iteration of socialism was not synonymous with Marxist socialism or Soviet-style central planning.

- The Constituent Assembly deliberately opted to exclude the term “socialist,” apprehensive that it might impose ideological rigidity and impede future democratic options.

- The socialism implemented after 1976 has evolved into democratic socialism, permitting private property and enterprise while mandating state accountability for welfare and equal distribution.

Secular

- India’s secularism, unlike Western approaches, prioritises equal reverence for all religions above a rigid separation of state and religion.

- Articles 25–28 of the Constitution ensure the freedom of conscience and religious practice while prohibiting religious education in state-funded institutions.

- The formal incorporation of “secular” into the Preamble in 1976 was to mitigate sectarian discord and confirm the state’s impartiality in religious affairs, notably as a challenge to Hindu nationalist discourses and to reaffirm India’s pluralistic identity.

Criticism and Counterarguments

RSS and Right-Wing Ideology

- The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its affiliated organisations have persistently contended that the inclusion of “socialist” and “secular” was undemocratic, implemented during a period of institutional fragility and repression of dissent.

- Dattatreya Hosabale, the RSS general secretary, and others assert that Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and the original framers did not anticipate such terminology, hence contending that its retroactive inclusion undermines the Constitution’s original spirit.

- The RSS contends that the prevailing interpretation of secularism has transformed into a mechanism for political appeasement, whereas socialism is an antiquated economic doctrine that constrains free entrepreneurship.

Constitutional and Judicial Perspective

- Conversely, legal and constitutional scholars contend that these expressions, even if introduced during the Emergency, only articulated what was always implied in the constitutional language.

- The Supreme Court of India has validated their legitimacy and strengthened its position as integral to the Constitution’s basic structure, exempt from amendment or deletion.

Constitutional and Judicial Significance

A. Fundamental Constitutional Provisions

- Article 14: Equality Before the Law

- Article 15: Prohibition of Discrimination

- Articles 25-28: Freedom of Religion

- Article 39(b) and (c): Equal distribution of resources and prevention of concentration of wealth

- Directive Principles of State Policy: Clearly embody socialist principles

B. Case Law

- Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) established the Basic Structure Doctrine, arguing that essential constitutional principles, such as secularism and judicial review, are immutable even by parliamentary amendment.

- Minerva Mills v. Union of India (1980); Invalidated sections of the 42nd Amendment that prioritised Directive Principles over Fundamental Rights. The Court determined that socialism and secularism, as currently articulated in the Preamble, were integral components of the Constitution’s fundamental framework.

- S.R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994): A pivotal lawsuit that established secularism as an essential element of the Constitution. It asserted that States are required to comply with secular norms and that activities fostering communalism may warrant the dismissal of State administrations.

- Dr. Balram Singh versus Union of India (2024): The Court affirmed the legitimacy of altering the Preamble under Article 368 and emphasised that India’s form of socialism is unique, permitting private property and a mixed economy. It also emphasised that secularism requires state neutrality, rather than antagonism, towards religion.

International Relevance and Comparative Perspective

- India’s constitutional identity as a secular and socialist democratic republic resonates on the world stage.

- In contrast to the United States, where secularism entails a total separation of church and state, India permits religious pluralism while upholding state neutrality.

- India’s socialist stance, however, has weakened since the 1991 economic liberalisation, paralleling the models of Scandinavian democracies that integrate market economies with robust social safety systems.

- India is not unique in its constitutional secularism; France (laïcité) and Turkey serve as other examples. However, the Indian approach integrates religion into public life while attempting to avert majoritarianism.

- India’s global reputation as the largest democracy is closely linked to its dedication to secularism and inclusive development.

- Any erosion or symbolic regression of these norms poses diplomatic and reputational repercussions, especially in international human rights arenas.

Political Stakes and Contemporary Debates

- The language of the Preamble has evolved into a symbolic battleground for competing ideological factions:

- The RSS-BJP framework aims to reaffirm cultural nationalism, frequently criticising the distortions of the Emergency period and challenging the conceptual permanence of socialism and secularism.

- The Congress and other secular parties accept the 1976 amendment as a valid reaffirmation of India’s pluralistic and equitable principles.

- Proposals to eliminate these phrases encounter legal obstacles (stemming from the basic structure theory) and political opposition from civil society and legislative dissent.

- Any effort to remove them is likely to rekindle past grievances and incite constitutional difficulties.

Reflection Over Revision

- Although it is legitimate to scrutinise the context and methodologies behind the 1976 incorporation of “socialist” and “secular,” the constitutional dedication to these ideals extends beyond their simple textual inclusion in the Preamble.

- They invigorate India’s judicial interpretations, governance frameworks, and ethical conception of democracy.

- As India progresses, the genuine challenge resides not in the retention of the words within the Preamble, but in the fidelity of their application in government, legislation, and societal practices.

- The discussion over removal should therefore shift from symbolic elimination to tangible implementation.

- According to Justice P.B. Gajendragadkar: “Secularism is more than a passive attitude of religious tolerance. It is a positive concept of equal treatment of all religions.”

- To preserve the constitutional essence of India, contemplation, not elimination, should direct our engagement with these fundamental principles.

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...