Table of Contents

Context: Despite being the world’s second-largest producer and consumer of fertilisers, India remains heavily dependent on imports for key raw materials and finished products. This dependence is both an economic vulnerability and an environmental concern.

| Data |

|

Why India is Heavily Dependent on Fertiliser Imports

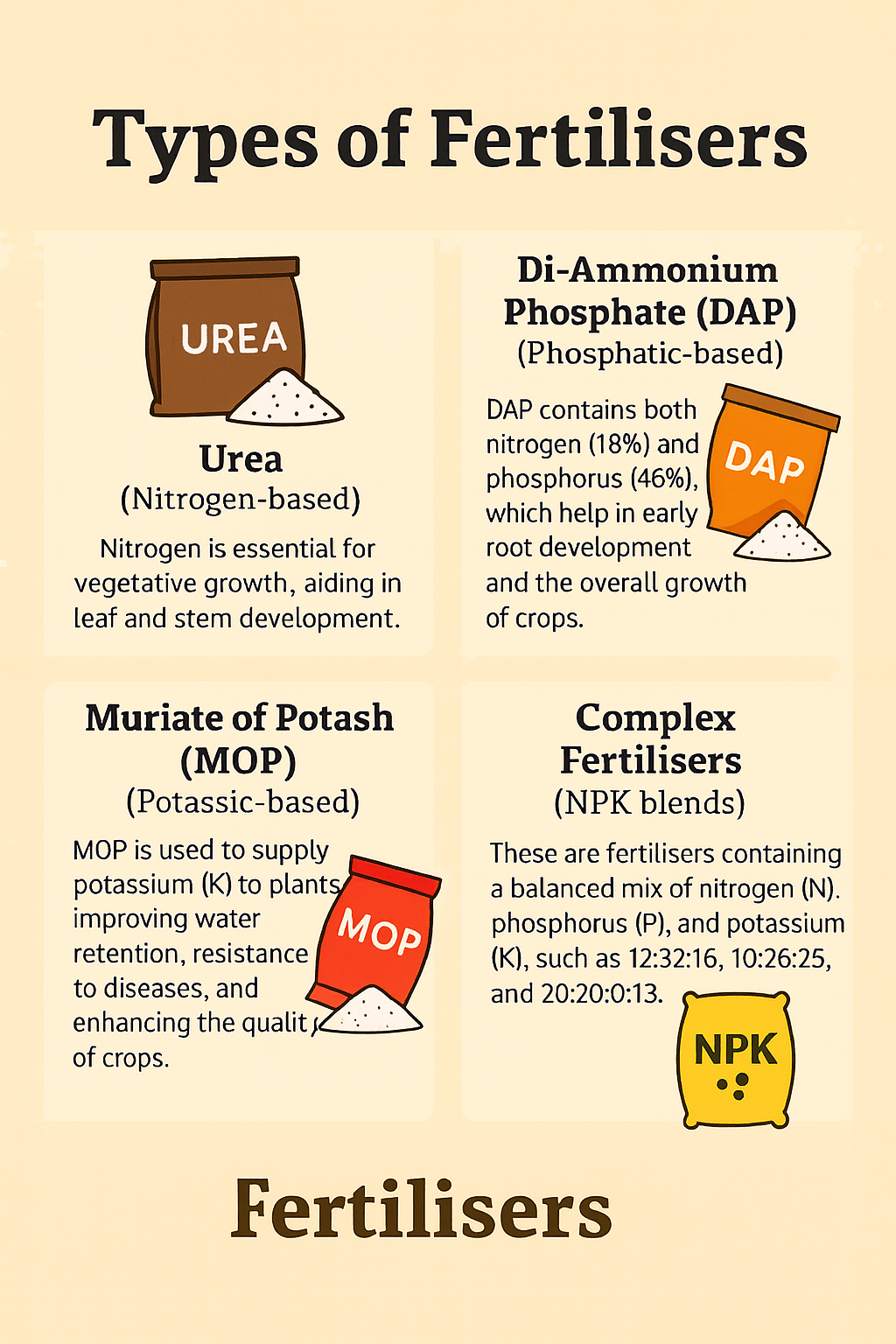

- Geological Constraints: India lacks significant reserves of phosphate rock and potash.

- Eg: the Entire Muriate of Potash (MOP) demand and 80% of phosphatic raw materials are imported.

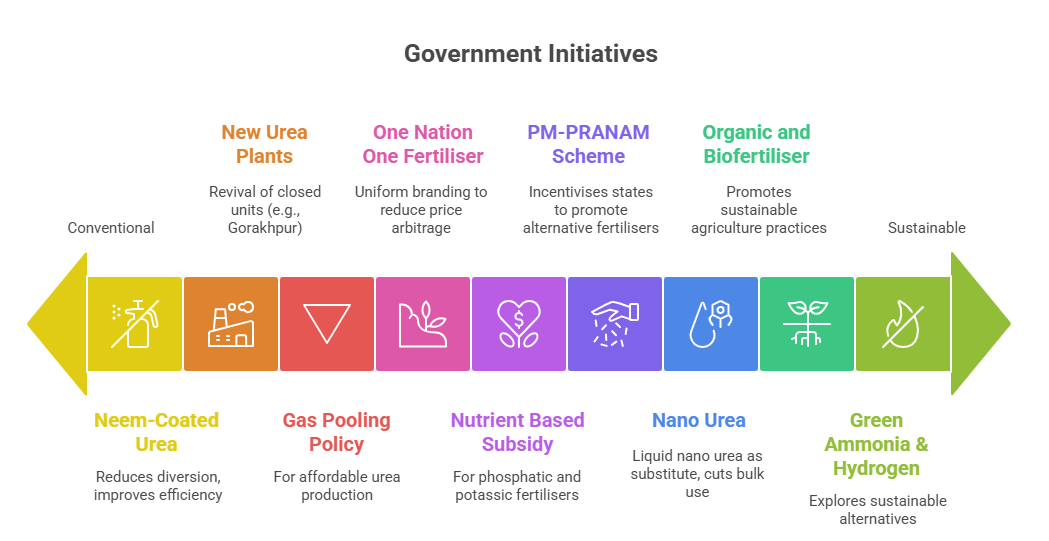

- Energy Dependence for Urea: Urea production depends on natural gas as feedstock.

- Eg: India imports 77% of its gas requirement for urea production (vs. 24% in 2012–13).

- Rising Domestic Demand: Fertiliser consumption has more than doubled since 2012-13.

- Eg: FY25-Total sales reached a record 655.94 lakh tonnes (lt) vs. 600.79 lt in FY24 (+9.2%).

- Insufficient Domestic Production Capacity: Despite being a major producer, India’s capacity is insufficient to meet demand.

- Subsidy-Driven Demand: Heavy subsidies, particularly on urea, encourage overuse and inefficiency, raising import needs.

Challenges in Fertiliser Production and Self-Sufficiency

Structural Challenges

- Raw Material Shortages: Lack of potash and phosphate reserves.

- Import-Linked Urea: Dependent on volatile international gas prices.

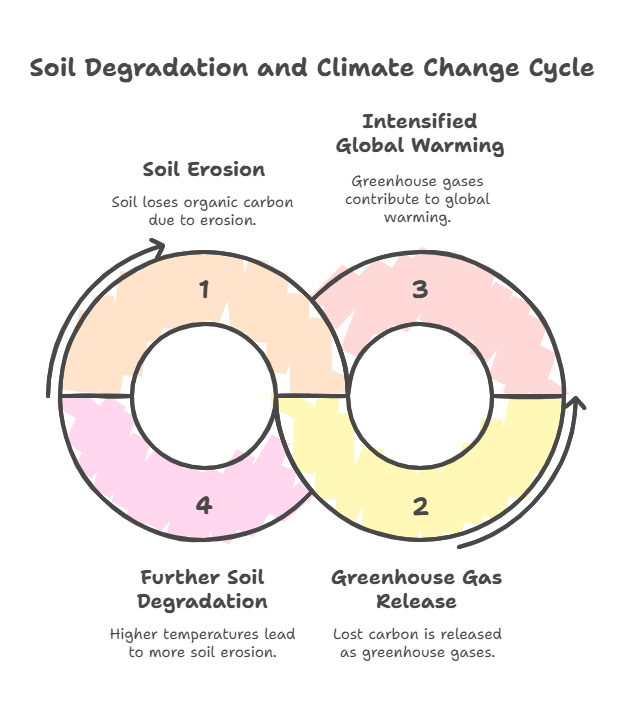

- Skewed Nutrient Use: Farmers in India use too much urea (nitrogen) and very little phosphorus (P) and potassium (K). This creates an unhealthy nutrient balance in the soil (current ratio 7:2.7:1 instead of the ideal 4:2:1)

Economic Challenges

- Rising Subsidy Burden: Fertiliser subsidies crossed ₹2 lakh crore in 2022–23, straining fiscal space.

- Rising fertiliser subsidies reduce the government’s fiscal space, distort domestic production, increase import dependence, and delay structural reforms

- Price Volatility: Geopolitical tensions (Russia-Ukraine war, West Asia) disrupt supplies and raise costs.

Governance Challenges

- Fragmented Administration: Fertilisers under a separate ministry; agriculture under another → inefficiency.

- Distribution Issues: Rationing, farmer queues, and diversion to non-agricultural use.

Technological Challenges

- Low Productivity of Plants: Many plants are old, energy-intensive, and uncompetitive compared to global producers.

- Slow adoption of alternatives: Nano Urea has promise (1 bottle = 1 bag of urea), but scaling up adoption and ensuring farmer acceptance remain challenges.

Alternatives & Missed Opportunities

- Organic manure, bio-fertilisers, and green ammonia could replace up to 30% of chemical fertiliser use, but lack a policy push.

- Subsidies remain skewed towards chemical fertilisers; organic alternatives cover <8% of sown area.

- India produces green ammonia, but exports it, as it isn’t yet approved for farm use.

| The Rising Soil Crisis |

|

Way Forward

- Diversify Sources & Secure Imports: Long-term contracts with multiple countries (e.g., Jordan, Morocco for phosphates; Canada, Russia for potash).

- Boost Domestic Alternatives: Scale up nano urea, nano DAP, and biofertilisers.

- Approve green ammonia for domestic farm use.

- Rationalise Subsidies: Balance subsidies between chemical and organic fertilisers.

- Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) to farmers instead of producers.

- Correct Nutrient Imbalance: Promote customised fertiliser blends based on soil health cards.

- Institutional Reform: Merge the fertiliser ministry with the agriculture ministry to align production, policy, and use.

- Encourage Private Sector & Innovation: Liberalise pricing and allow private players to invest in organics, biofertilisers, and new technologies.

World Wetlands Day 2026: Theme, History,...

World Wetlands Day 2026: Theme, History,...

Geological Heritage Sites of India: Sign...

Geological Heritage Sites of India: Sign...

Wildlife Sanctuaries of India 2026: List...

Wildlife Sanctuaries of India 2026: List...