Table of Contents

The recent issue about the forceful repatriation or “pushback” of Indian citizens alleged to be illegal Bangladeshi migrants has rekindled a multifaceted discourse on immigration regulation, national security, and constitutional protections. The case, in which citizens from West Bengal and Assam were unjustly removed and subsequently reinstated after verification, highlights the delicate equilibrium between state sovereignty and individual rights. This matter also highlights issues of procedural fairness, due process, and the humanitarian responsibilities of a democratic state.

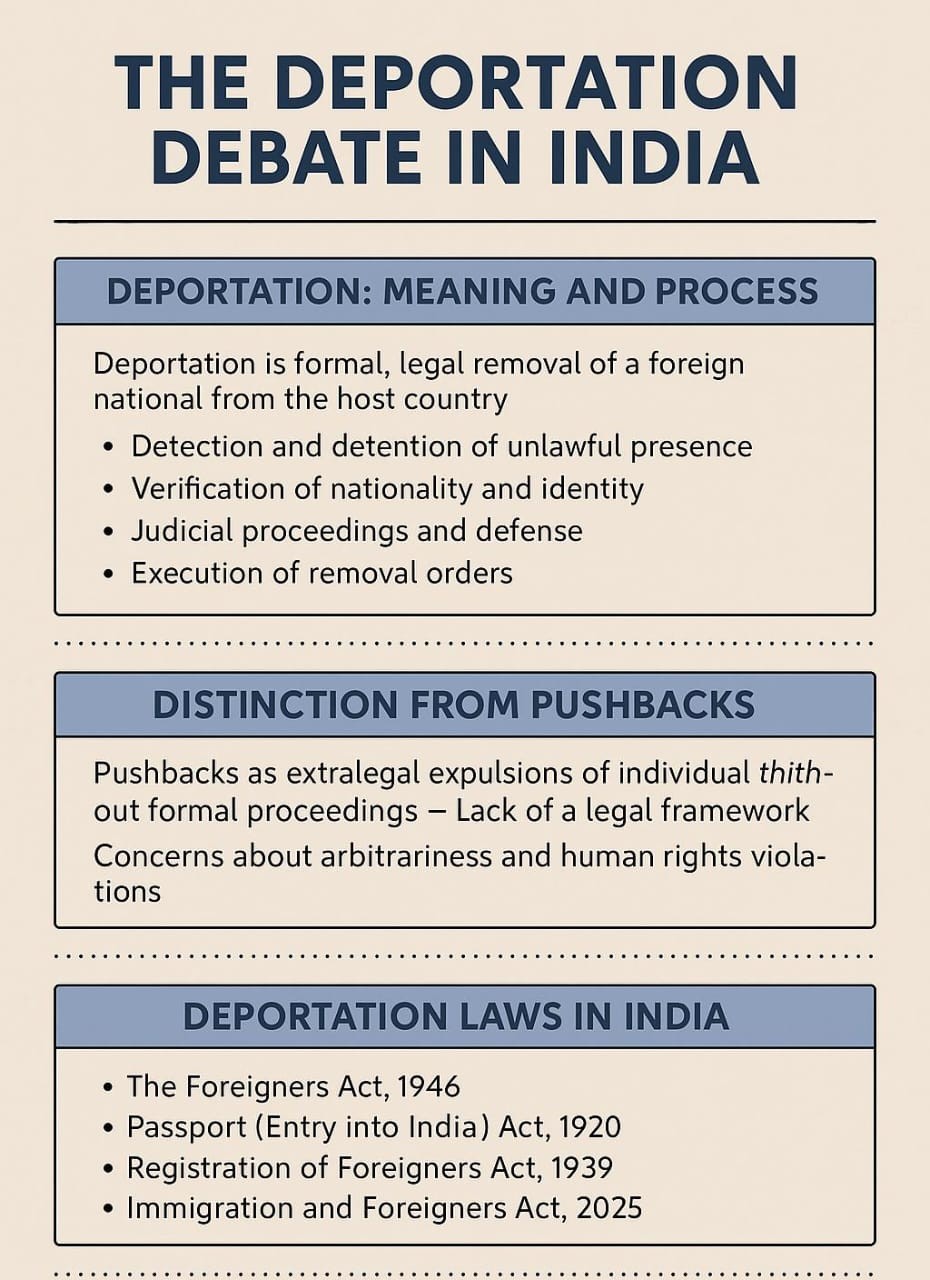

Understanding Deportation: Meaning and Process

- Deportation is the official, legal removal of a foreign individual from a host nation due to causes such as unauthorised admission, visa overstay, or engagement in illicit activities. In India, deportation is a legal procedure that often entails:

-

- Identification and apprehension of an unlawfully present foreign national.

- Authentication of nationality and identity via consular access or diplomatic avenues.

- Judicial proceedings in which the individual is afforded the opportunity to provide a defence.

- Implementation of removal orders after the exhaustion of all legal remedies.

- Deportation must adhere to due process of law, as stipulated by Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees the right to life and personal liberty to “all persons,” including non-citizens.

Distinguishing Deportation from Pushbacks

- In contrast to deportation, pushback is an extralegal administrative action in which persons are swiftly ejected from the border without formal procedures.

- In India, pushbacks lack a formal legal foundation and depend on the discretionary authority of the Border Security Force (BSF).

- The absence of a legal framework renders pushbacks susceptible to capricious actions, human rights infringements, and misidentification, as seen by the recent episode in West Bengal.

- Pushbacks, although presented as strategies to mitigate illegal migration, contravene the principle of non-refoulement, a customary international rule that forbids the return of individuals to regions where they encounter threats to their life or liberty.

Constitutional Provisions and Citizenship Safeguards

- Article 21: Ensures the right to life and liberty for all individuals, not exclusively citizens. Any expulsion lacking due process violates this protection.

- Article 14: Ensures equality before the law. Arbitrary deportations or pushbacks contravene the concept of equal treatment under the law.

- Article 19: The misuse of identification systems or erroneous labelling based on language or region (e.g., Bengali-speaking individuals), although restricted to citizens, presents constitutional issues under Article 15 (prohibition of discrimination).

- The federal framework designates immigration and citizenship as Union subjects in List I (Entry 17) of the Seventh Schedule. Nonetheless, enforcement is frequently assigned to state police agencies, resulting in inconsistencies and a deficiency of due process.

- The centralisation of immigration issues restricts the ability of states like Mizoram, Manipur, and Nagaland to autonomously address refugee influxes, like as the Chin migrants from Myanmar, hence questioning federal autonomy and responsibility.

Legal Framework Governing Deportation in India

- The Foreigners Act of 1946 (Repealed by the Act of 2025)– This Act empowered the Central Government to oversee the admission, residency, and expulsion of foreigners. It conferred broad authority to hold and deport anyone suspected of unlawful residency.

- Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920– It mandated that foreigners possess legitimate travel documents and imposed penalties for illegal admission.

- Registration of Foreigners Act of 1939– Required foreigners to notify authorities, facilitating monitoring and enforcement.

- Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025– Enacted in April 2025, this Act consolidates previous legislation and modernises immigration administration. It seeks to optimise deportation processes and improve collaboration between Central and State authorities. The operational specifics and protections under this Act are still being revealed.

- Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act, 1950– This specific Act authorises the Union Government to mandate the expulsion of individuals from Assam if they are considered detrimental to the public interest or tribal well-being. The Act, recently referenced by Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, raises concerns as it empowers District Commissioners to designate individuals as illegal immigrants, a capability susceptible to exploitation in the absence of judicial scrutiny.

Relevant Case Laws

- Sarbananda Sonowal v. Union of India (2005)- The Supreme Court annulled the Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunals) Act, 1983, finding that it obstructed the identification and expulsion of illegal migrants in Assam. The Court upheld the State’s authority to control immigration in the interest of national interest.

- Mohammad Salimullah v. Union of India (2021)– The Supreme Court permitted the repatriation of Rohingya refugees held in Jammu, asserting that India is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention. Nonetheless, it did not explicitly negate non-refoulement.

- National Human Rights Commission v. State of Arunachal Pradesh (1996)– The Court determined that even undocumented migrants had the right to dignified treatment and could not be forcibly removed without due process as stipulated in Article 21.

- These instances illustrate the judiciary’s intricate balancing act between national security and human rights.

Recent Governmental Drives and Human Rights Concerns

- After the April 2025 terrorist assault in Pahalgam, the Home Ministry commenced Operation Sindoor to identify and deport unauthorised migrants.

- Many individuals were transported to Tripura and purportedly forced across the border without due process or proof.

- The BSF has not recognised these operations, and biometric data was allegedly gathered without consent.

- There is apprehension that Bengali-speaking Indian residents, especially Muslims and Adivasis, are being profiled and targeted on suspicion of being Bangladeshis.

- This presents significant constitutional and ethical concerns regarding discrimination, due process, and governmental overreach.

International Perspective and Non-Refoulement Obligations

- Although India is not a member of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, the concept of non-refoulement, which prohibits returning refugees to nations where they face danger, is recognised as customary international law.

- The pertinent international legal frameworks include:

-

- Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) acknowledges the right to seek refuge.

- India, as a member of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), is obligated to uphold rights, including the right to a fair trial and protection against arbitrary imprisonment, as stipulated in Articles 9 and 13.

- The Convention Against Torture (CAT)– Despite India’s non-ratification, international courts regard deportation without safeguards as a possible violation of human rights.

- India’s pushback policy may thus subject it to scrutiny in international human rights forums, particularly if expulsions occur without consular verification, legal assistance, or oversight.

Way Forward

- Institutionalise Pushback Protocols: Develop a legislative structure incorporating human rights protections to govern border operations.

- Guarantee Due Process: Compulsory court review prior to any expulsion, including provision for legal counsel.

- Biometric and Identity Protections: Utilise Aadhaar judiciously and refrain from categorising persons on “negative lists” without avenues for redress.

- Refugee Law Framework: Consider implementing a national refugee statute to address stateless individuals and those escaping persecution.

- Community Engagement: Mitigate erroneous profiling by educating law enforcement about diversity, linguistics, and cultural awareness.

- The current deportation and pushback initiatives, particularly in states like Assam and West Bengal, provoke significant inquiries on the rule of law, procedural equity, and individual rights within a constitutional democracy.

- Although national security and border integrity are valid issues, they must not supersede the fundamental constitutional principles of equality, liberty, and justice.

- An equitable, legally compliant, and rights-respecting strategy for immigration enforcement is crucial for both domestic stability and the preservation of India’s adherence to international humanitarian norms.

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...