Table of Contents

Why in the news?

On December 3, the Supreme Court issued comprehensive directives to enhance the implementation of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 (POSH Act). These measures aim to fortify compliance, particularly in sectors with inconsistent enforcement. The Court emphasised the need for effective POSH Act implementation in the private sector, which has historically been slow to comply. A notable issue is the reluctance of many organizations to establish Internal Complaints Committees (ICCs) essential for addressing workplace harassment.

All States and Union Territories were ordered to submit affidavits confirming compliance with the Act, detailing efforts to form Local Complaints Committees (LCCs) and appoint District Officers responsible for managing complaints in workplaces lacking ICCs.

The Court mandated that District Officers be appointed by December 31, 2024, to ensure oversight of POSH Act compliance in every district. Additionally, Local Committees must be reconstituted by January 31, 2025, to guarantee formal complaint mechanisms are available, especially in smaller workplaces.

The Supreme Court directed that the list of District Officers be published on the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) website and encouraged States to display this information on their Department of Women and Child Development websites for greater transparency.

The Union Government expressed concerns about private sector non-compliance, as many organizations have not set up ICCs as required by law. Several States, including Delhi, Haryana, Jharkhand, and Kerala, submitted incomplete compliance reports, prompting the Court to request further affidavits for verification. Although some States conducted surveys on compliance, issues with data accuracy and completeness persist. These directives represent a significant move toward improving workplace safety and accountability, highlighting the critical role of institutional mechanisms in effectively addressing sexual harassment.

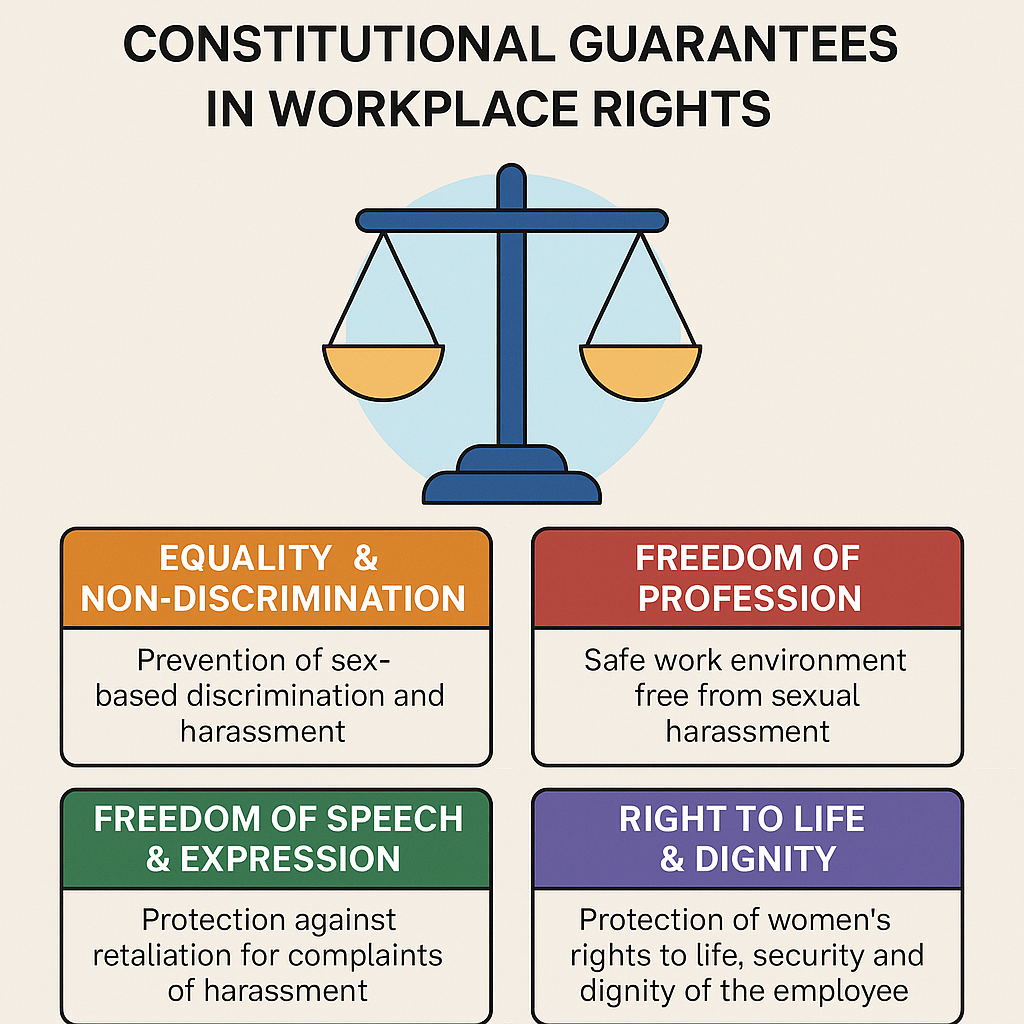

Constitutional Guarantees in Workplace Rights in India

Constitutional guarantees in workplace rights refer to the protections embedded within a country’s fundamental legal framework that safeguard employees’ rights, ensuring fair treatment, equality, and access to essential benefits. These guarantees often intersect with labour laws, which regulate employer-employee relationships, working conditions, and entitlements. One particularly important area of discussion is reproductive healthcare policies, which encompass maternity benefits, workplace accommodations for pregnant employees, and protections against discrimination based on reproductive choices.

Labour laws provide specific provisions for workers’ rights, but constitutional principles such as equality before the law, non-discrimination, and the right to dignity enhance their effectiveness. Some key intersections include:

- Right to Equality (Article 14 in India) ensures that employees are not discriminated against on the basis of gender, pregnancy, or reproductive choices. The right supports affirmative action policies for women, such as reservation in government jobs or targeted workplace benefits.

- Right Against Discrimination (Article 15) prohibits discrimination based on sex, which forms the foundation of laws preventing workplace harassment and biased hiring practices. It strengthens maternity protections by ensuring women are not penalized for pregnancy or motherhood in employment decisions.

- Right to Life and Dignity (Article 21) expands workplace protections to include reasonable accommodations, such as maternity leave, breastfeeding spaces, and access to reproductive healthcare. It supports laws mandating humane working conditions and ensuring employees have access to health benefits.

- Right to Health and Safety (Directive Principles of State Policy) encourages policy initiatives ensuring access to paid maternity leave, childcare support, and reproductive health programs within workplaces. It forms the basis for Occupational Safety standards related to reproductive health hazards.

Reproductive Healthcare Policies in Workplace Law

Reproductive healthcare in the workplace is an evolving domain, influenced by both statutory labour laws and constitutional protections. Some core aspects include:

- Maternity Benefits: Most countries have legislation mandating maternity leave, ensuring job security during pregnancy and postpartum recovery.

- Paternity and Parental Leave: While traditionally focused on mothers, many legal systems now recognise parental leave as essential for gender equality in caregiving.

- Non-Discrimination: Policies ensuring women are not overlooked for promotions, hiring, or wages due to their reproductive choices.

- Workplace Accommodations: Laws requiring employers to provide support, like flexible work hours for new mothers, breastfeeding rooms, or extended childcare assistance.

Challenges and Emerging Issues

Despite strong constitutional guarantees, enforcement of workplace rights varies, leading to disparities between legal protections and practical implementation. Many corporate workplaces struggle with full compliance, especially in informal employment settings. Countries are now expanding reproductive healthcare protections to cover surrogacy, adoption, miscarriage recovery, and fertility treatments under workplace entitlements.

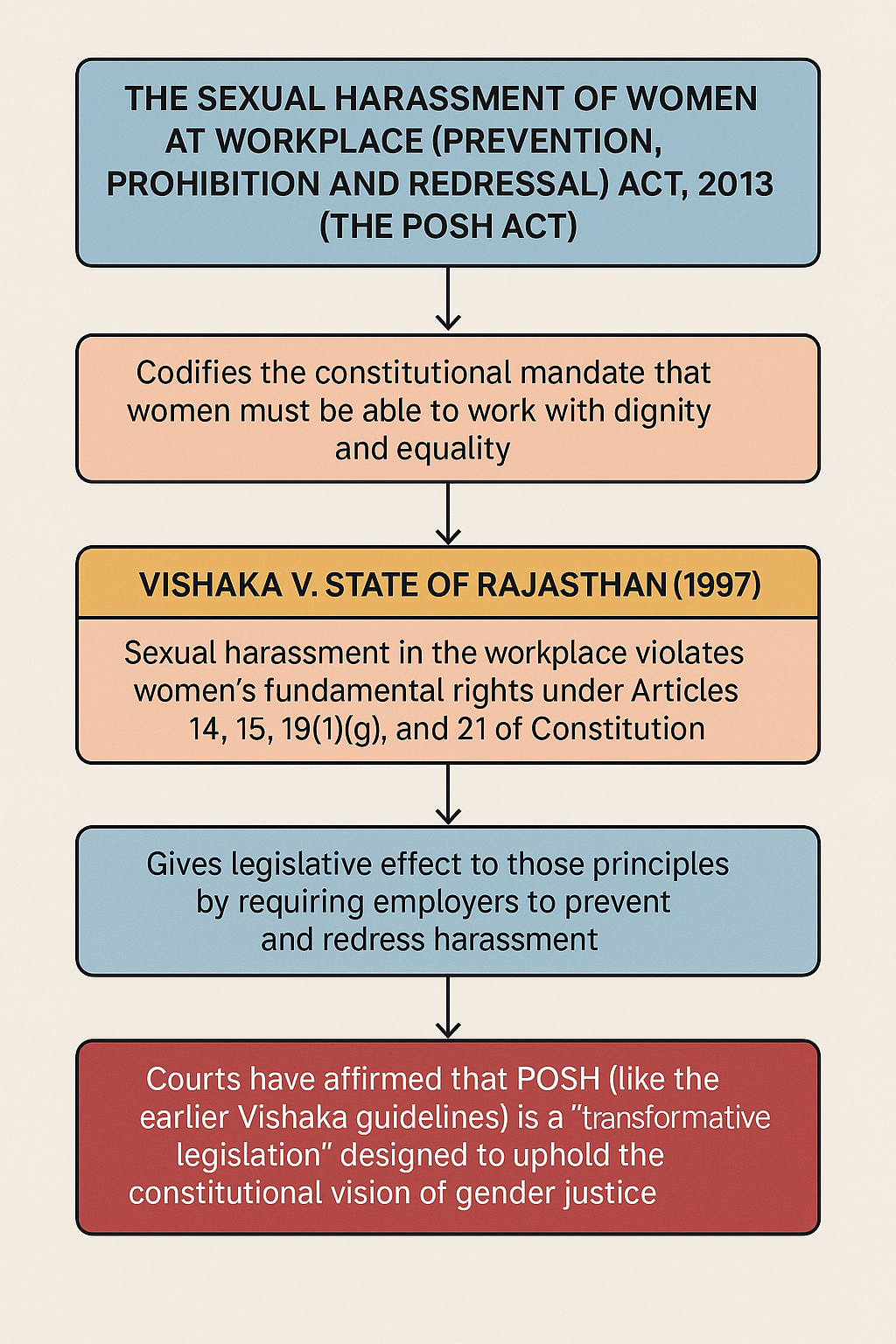

POSH Act 2013 and Fundamental Rights

The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 (the POSH Act) codifies the constitutional mandate that women must be able to work with dignity and equality. In Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan (1997), the Supreme Court declared that sexual harassment in the workplace violates women’s fundamental rights under Articles 14, 15, 19(1)(g) and 21 of the Constitution.

The POSH Act gives legislative effect to those principles by requiring employers to prevent and redress harassment. In short, the Act implements the Constitution’s guarantees of equality and non-discrimination, protects the freedom to work, and secures the right to life and dignity for women in the workplace. As one analysis notes, “sexual harassment of a woman at the workplace is the violation of [her] fundamental right under Articles 14, 15, 21 and 19(1)(g)”. Courts have affirmed that POSH (like the earlier Vishaka guidelines) is a “transformative legislation” designed to uphold the constitutional vision of gender justice.

Articles 14 & 15 – Equality and Non-Discrimination

Articles 14–15 forbid arbitrary or sex-based discrimination and promise equal protection under the law. Sexual harassment is inherently discriminatory: it treats women differently on account of sex and undermines their equal status at work. POSH expressly targets this inequality. For example:

- Sex-based protection: Article 15(1) prohibits discrimination on the grounds of sex. Article 15(3) empowers special provisions for women, and the POSH Act is such a measure. The Supreme Court observed that POSH was “framed with regard to Article 15(3) … in order to extend the constitutional right of equality and equal protection of the laws to women”. In other words, POSH is a constitutionally authorized special law aimed at remedying women’s disadvantage and ensuring equal legal protection.

- Equal remedies and procedure: Article 14 demands that state action be reasonable and fair. POSH enforces procedural safeguards to meet this standard. Section 4(1) of POSH mandates that every employer constitute an Internal Complaints Committee (ICC) by order in writing. This uniform requirement prevents arbitrariness and ensures that all eligible women have access to an impartial grievance forum – a direct application of Article 14’s rule of law. Likewise, POSH sets out mandatory timelines and inquiry procedures, reflecting Article 14’s insistence that decisions be “informed by reason” .

- Prohibition of discriminatory conduct: The Act criminalizes quid-pro-quo harassment and hostile-environment harassment specifically as sex-based wrongdoing. By defining these acts as unlawful misconduct, POSH treats them as prohibited sex discrimination (squarely within Article 15’s scope). As one scholarly commentary explains, harassment at work “results in violation of the fundamental rights of a woman to equality under Articles 14 and 15… and her right to live with dignity under Article 21”. POSH therefore, transforms the equality norm into concrete workplace rules and penalties, closing the gap between constitutional promise and reality.

Together, these provisions mean that a female employee is not left to endure unequal treatment or a hostile work climate. Courts have highlighted that allowing harassment to persist would “dilute the whole purpose” of protective laws and violate women’s equality guarantees. In line with Vishaka, the Act implements the constitutional right to non-discrimination by empowering women to complain and by obliging employers to treat men and women equally in all terms of employment.

Article 19 – Freedoms of Speech/Expression and Profession

Article 19(1)(g) guarantees every citizen the right to practice any profession or carry on any occupation. Sexual harassment in the workplace directly impedes this freedom: an unsafe or abusive environment deters women from working or forces them out of their profession, violating the very right to pursue a livelihood. The POSH Act protects Article 19 rights by mandating a safe, harassment-free work environment. In particular:

- Safe workplace for profession: POSH explicitly aims “to foster a safe and secure working environment for women by preventing, prohibiting, and redressing … sexual harassment”. This legislative objective reinforces women’s ability to freely engage in their chosen professions (Art. 19(1)(g)) without fear. A secure workplace means women can exercise their right to work and earn a living in dignity – a core Article 19 guarantee. As one commentator observes, ensuring a safe and respectful work environment is a woman’s legal right.

- Free expression of grievances: Freedom of speech and expression (Art. 19(1)(a)) includes the right of employees to speak out about workplace conditions. Harassment often silences victims; POSH counters this by protecting complainants. The Act prohibits retaliation against anyone who complains of harassment, and it requires all proceedings to be confidential. These rules encourage women to report misconduct without fear, essentially preserving their Article 19(a) right to communicate about issues in the workplace. Courts have noted that a lawful grievance process must not become a “punishment” for victims, and POSH’s safeguards (confidential inquiries, nondisclosure of identities, etc.) operationalize that principle.

In sum, by establishing formal redressal mechanisms and prohibiting discriminatory behavior, the POSH Act upholds Article 19 freedoms. It ensures that women can continue to work and express themselves in the workplace on equal footing. The Supreme Court has underscored this link: sexual harassment was recognized as violating women’s right to work with dignity, implicating both Article 19(1)(g) and Article 21. The Act’s provisions (e.g. mandatory inquiry committees and awareness programs) put this into effect, aligning statutory protections with the Constitution’s guarantees of free profession and speech.

Article 21 – Right to Life, Liberty and Dignity

Article 21 guarantees that no person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty except by a fair procedure. The right to life under Article 21 has been expansively interpreted to include living with human dignity and personal security. The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that sexual harassment at work violates this right. For example, in Mudrika Singh v. Uttar Pradesh (2021) the Court emphatically stated that the “right against sexual harassment is vested in all persons as a part of their right to life and right to dignity under Article 21”. It warned that courts must “uphold the spirit” of this right and avoid dismissing complaints on hyper-technical grounds. By framing anti-harassment norms as fundamental to Article 21, the judiciary has made clear that women’s bodily autonomy and psychological well-being at work are constitutionally protected.

The POSH Act enforces these protections through concrete mechanisms: it criminalizes sexual harassment as an offence and prescribes mandatory institutional responses. Sections 13–22 of the Act prescribe inquiry procedures and punishments (including fines and cancellation of service) for confirmed acts of harassment. These legal tools serve to enforce a woman’s Article 21 rights by deterring offenders and redressing violations. For instance, if an employee is found guilty of harassment, the employer “shall proceed against the respondent for such misconduct” under service rules, ensuring the perpetrator is punished.

The Act also encourages women to seek civil or criminal remedies (e.g. filing charges under the Penal Code) without fear. Collectively, these measures give life to Article 21’s guarantee that every person has the right to a life of dignity and security. As one study notes, Article 21 “secures that no person shall be deprived of his/her life and sexual harassment of a woman at the workplace is the violation of this right”. POSH, therefore, aligns the statutory scheme with the constitutional imperative that a person’s right to livelihood and dignity not be nullified by exploitation or abuse.

Judicial Authority and Constitutional Values

The linkage between POSH and fundamental rights has been repeatedly affirmed by the judiciary. In Vishaka v. Rajasthan (1997), the Court declared that guidelines against workplace harassment flowed from Articles 14, 15, 19 and 21, and that failure to prevent harassment would violate those rights. Subsequent cases have echoed that ethos. For example, the Court in Nipun Saxena v. Union of India and Mudrika Singh admonished that statutory protections for women must be construed broadly to effectuate constitutional values, not frustrated on technicalities. Courts have also stressed the Act’s “transformative” character that it gives substance to women’s equality and dignity.

In the spirit of the Constitution, POSH operationalises fundamental duties as well as rights. Article 51A(e) of the Constitution imposes a duty on every citizen to “renounce practices derogatory to the dignity of women.” By outlawing sexual harassment, POSH is a concrete response to that duty and to the Preamble’s promise of equal justice. As Justice Bhagwati famously observed, “Law cannot stand still; it must change with the changing social concepts and values.”. The enactment of POSH is a prime example of this principle in action: it updates the legal landscape to protect women’s evolving role in the workforce and to uphold the Constitution’s guarantees of gender justice.

In sum, the POSH Act is deeply grounded in India’s constitutional scheme. It translates the abstract guarantees of Articles 14, 15, 19 and 21 into concrete workplace rights – equality of opportunity, freedom to work, and life with dignity. By requiring preventive policies, complaint mechanisms, and penalties for harassment, the Act enforces those fundamental rights. Courts have made clear that combating sexual harassment is part and parcel of the constitutional vision for a just, equal and dignified society. In this way, the POSH Act not only aligns with but actively furthers the spirit of the Constitution, ensuring that no woman’s right to equality or dignified life is compromised at work.

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...