Table of Contents

The Supreme Court of India, as the custodian of the Constitution, is anticipated to reflect the principles of equality, inclusion, and justice. Nonetheless, its institutional framework exhibits a pronounced gender disparity. The retirement of Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia in August 2025 resulted in two vacancies in the Court, although women were again disregarded for appointment. Justice B.V. Nagarathna is the only female judge on a fully constituted bench of 34 members. This underrepresentation not only jeopardises the integrity of the judiciary but also subverts constitutional principles of equality and representation.

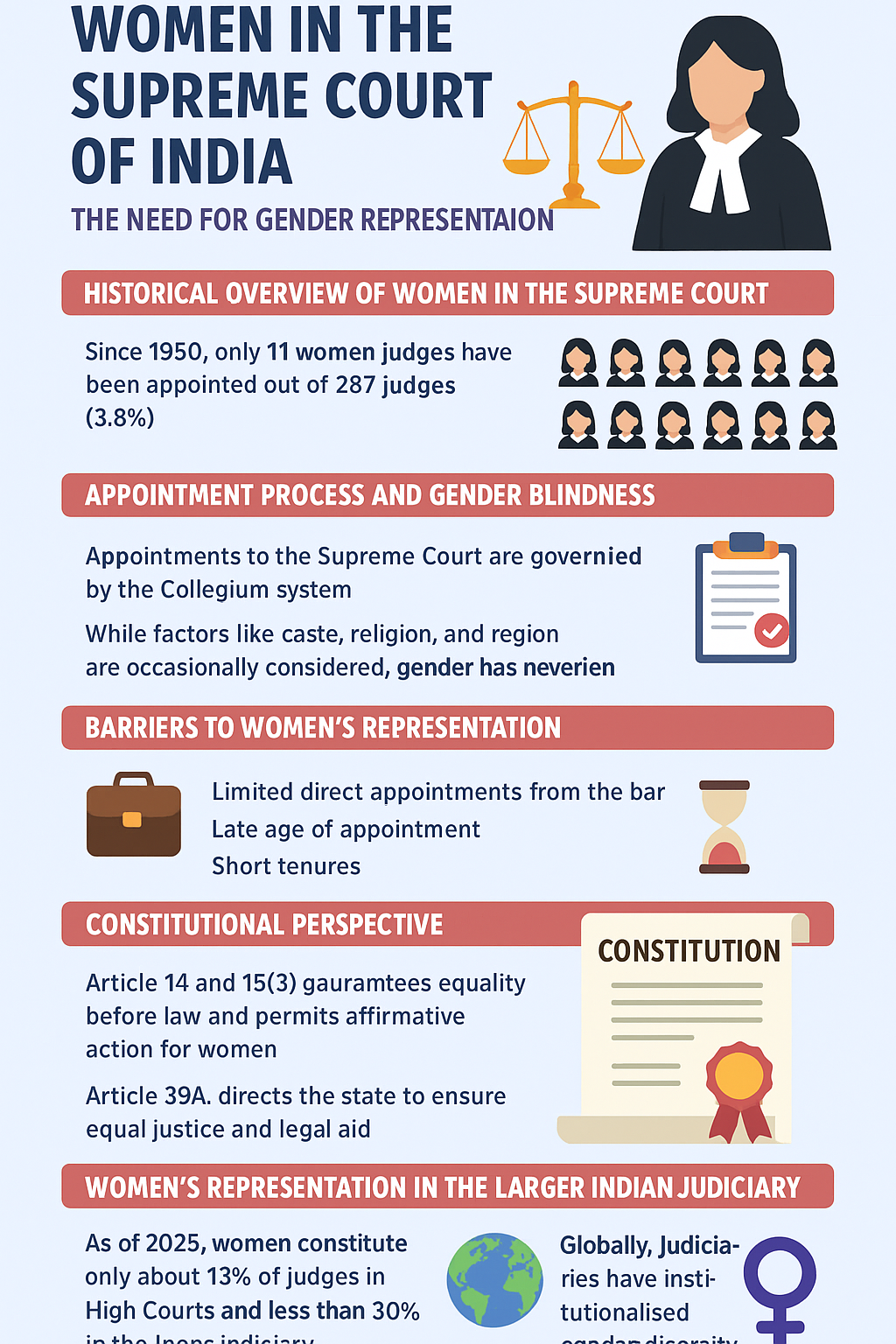

Chronological Account of Women in the Supreme Court of India

- Since its establishment in 1950, merely 11 women judges have been appointed from a total of 287 judges (3.8%).

- Justice Fathima Beevi became the first female judge in 1989.

- Subsequent appointments comprise Justices Sujata Manohar, Ruma Pal, Gyan Sudha Mishra, Ranjana Prakash Desai, R. Banumathi, Indu Malhotra, Indira Banerjee, Hima Kohli, Bela M. Trivedi, and B.V. Nagarathna.

- The 2021 Collegium, led by CJI N.V. Ramana, selected three women judges simultaneously, representing the first instance of female representation exceeding 10% in the Court.

- Nonetheless, representation is limited, without women from the Scheduled Castes, the Scheduled Tribes, or Other Backwards Classes, with only Justice Fathima Beevi representing a minority faith.

Appointment Procedure and Gender Neutrality

- Supreme Court appointments are regulated by the Collegium system, wherein the Chief Justice of India (CJI) and four senior-most judges propose candidates.

- While variables such as caste, religion, and geographical region are often acknowledged, gender has never been formalised as a criterion.

- The Memorandum of Procedure does not require gender representation.

- The discussions of the collegium lack transparency, accompanied by conflicting public rationale for appointments.

- Former Chief Justices of India have frequently cited the “non-availability of senior women” as a reason for the scarcity of women judges, despite the continued oversight of numerous senior female justices in High Courts.

- Justice may be blind, but it should not be indifferent to gender. Data indicates that India’s highest-performing High Courts are also the most gender-representative.

- In March 2025, Telangana had 10 female judges out of 30, with the lower judiciary exhibiting a notable 50% female participation. Sikkim has 33.3% women judges, while Manipur has 25%. Conversely, states such as Meghalaya, Tripura, and Uttarakhand had no female judges at all.

- Nevertheless, women continue to be underrepresented in higher courts. The absence of representation is significant, not due to the assumption that women are inherently more progressive than men, but because judges from varied backgrounds contribute their lived experiences to the decision-making process. Senior counsel Jayna Kothari asserts that diversity enhances court decisions.

- Senior advocate Indira Jaising contends that representation transcends mere symbolism; female judges possess empathy derived from their personal experiences of exclusion, enabling them to relate to others confronting similar challenges.

- The issue lies not in the scarcity of competent women, but in inequitable standards. In 1984, when Sunanda Bhandare’s nomination for the Delhi High Court was put up, Chief Justice Yeshwant Chandrachud dismissed it, asserting she was “too young” at 42, despite having been appointed a High Court judge at 40 himself. This illustrates the bias women encounter in judicial nominations.

Obstacles to Women’s Representation

- Restricted Direct Appointments from the Bar: Since 1950, nine male judges have been appointed directly from the Bar; however, just one woman, Justice Indu Malhotra (2018), has achieved this distinction.

- Delayed Appointment Age: Female judges are frequently chosen at older ages, which diminishes their tenure and opportunities to join the Collegium.

- Justice Nagarathna, set to be the first female Chief Justice of India in 2027, will hold the position for merely 36 days.

- Brief Tenures: Justices Beevi and Malhotra had tenures of less than three years, constraining their influence and leadership chances.

Constitutional Viewpoint

- Article 14 ensures legal equality, whereas Article 15(3) allows for affirmative action in favour of women.

- Article 39A (Directive Principles) mandates the state to guarantee equitable justice and legal assistance.

- The Preamble’s dedication to equality and justice requires gender inclusion within the judiciary.

- The Supreme Court has progressed gender equality jurisprudence, for instance:

- Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan (1997) – directives against workplace harassment.

- Joseph Shine v. Union of India (2018) – invalidation of the adultery statute due to its discriminatory nature.

- Secretary, Ministry of Defence v. Babita Puniya (2020) – awarding permanent commission to women in the military.

- The irony resides in the Court’s advancement of gender equality through rulings, while it remains institutionally inequitable.

Perspectives from the Judiciary

- CJI N.V. Ramana (2021): “Representation of women in the judiciary has to be increased. Women should demand reservation in the judiciary as a matter of right.”

- CJI D.Y. Chandrachud (2023): “Inclusion of women in the judiciary is not a matter of charity, but of right. Diversity on the bench strengthens justice delivery.”

- Both of them acknowledged the systemic marginalisation of women and emphasised the necessity for structural reforms.

Representation of Women in the Indian Judiciary

- By 2025, women will represent merely 13% of judges in High Courts and under 30% in the lower judiciary.

- Numerous High Courts, like those in Patna and Manipur, have experienced prolonged periods without female judges.

- The omission of women from Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and other marginalised groups underscores intersectional marginalisation.

The Global Aspect

- Worldwide, judiciaries have formalised gender diversity.

- The U.K. Supreme Court has consistently appointed women, notably Lady Brenda Hale, as President.

- The U.S. Supreme Court presently comprises four female justices: Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Amy Coney Barrett, and Ketanji Brown Jackson.

- Canada requires representation from women and minorities, resulting in more equitable benches.

- The Constitutional Court of South Africa has undertaken affirmative measures to guarantee gender and racial diversity.

- In comparison to these jurisdictions, India is well behind. Gender representation in the higher judiciary is not mandatory, rendering India an anomaly among democracies that prioritise diversity.

The Importance of Increasing Female Judges

- Diverse Perspectives: Female judges contribute experiential diversity, enhancing judicial decision-making.

- Public Trust: Enhanced inclusion fosters confidence in the judiciary as a representational entity.

- Substantive Equality: Representation actualises the constitutional commitment to equality.

- Role Models: Female judges motivate younger women in the legal field, reinforcing the professional pipeline.

Path Forward

- Institutionalise Gender as a Criterion, in conjunction with caste, region, and religion.

- Transparent Collegium Procedure– including transparent rationale for appointments.

- Direct Elevation from the Bar– proactively designate women as Senior Advocates.

- Affirmative Action Policy– to guarantee representation of women across various castes, religions, and regions.

- Younger appointments – to facilitate extended tenures and enhanced leadership chances.

Conclusive Remarks

- Despite its proactive role in promoting gender equality, the Supreme Court of India has not adequately embodied this principle within.

- Institutionalising gender diversity is not merely a matter of tokenism; it is a constitutional need.

- The inclusion of additional female judges would enhance jurisprudence, fortify democracy, and render the judiciary more representative of Indian society.

- As India anticipates its first female Chief Justice of India, although for a mere 36 days, the imperative is a systemic transformation that guarantees women are not merely exceptions but essential components of the judiciary.

- Many contend that it is now imperative to implement more stringent measures, potentially including quotas, akin to the Women’s Reservation Bill in Parliament.

- Distributing power has historically been challenging; thus, an institutional mandate is essential to guarantee the advancement of women to higher courts.

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg famously remarked of the US Supreme Court, in response to the question concerning the sufficiency of female judges: “When there are nine.” It may be time for Indian women to demand representation for all 34 positions in the Supreme Court.

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...