Table of Contents

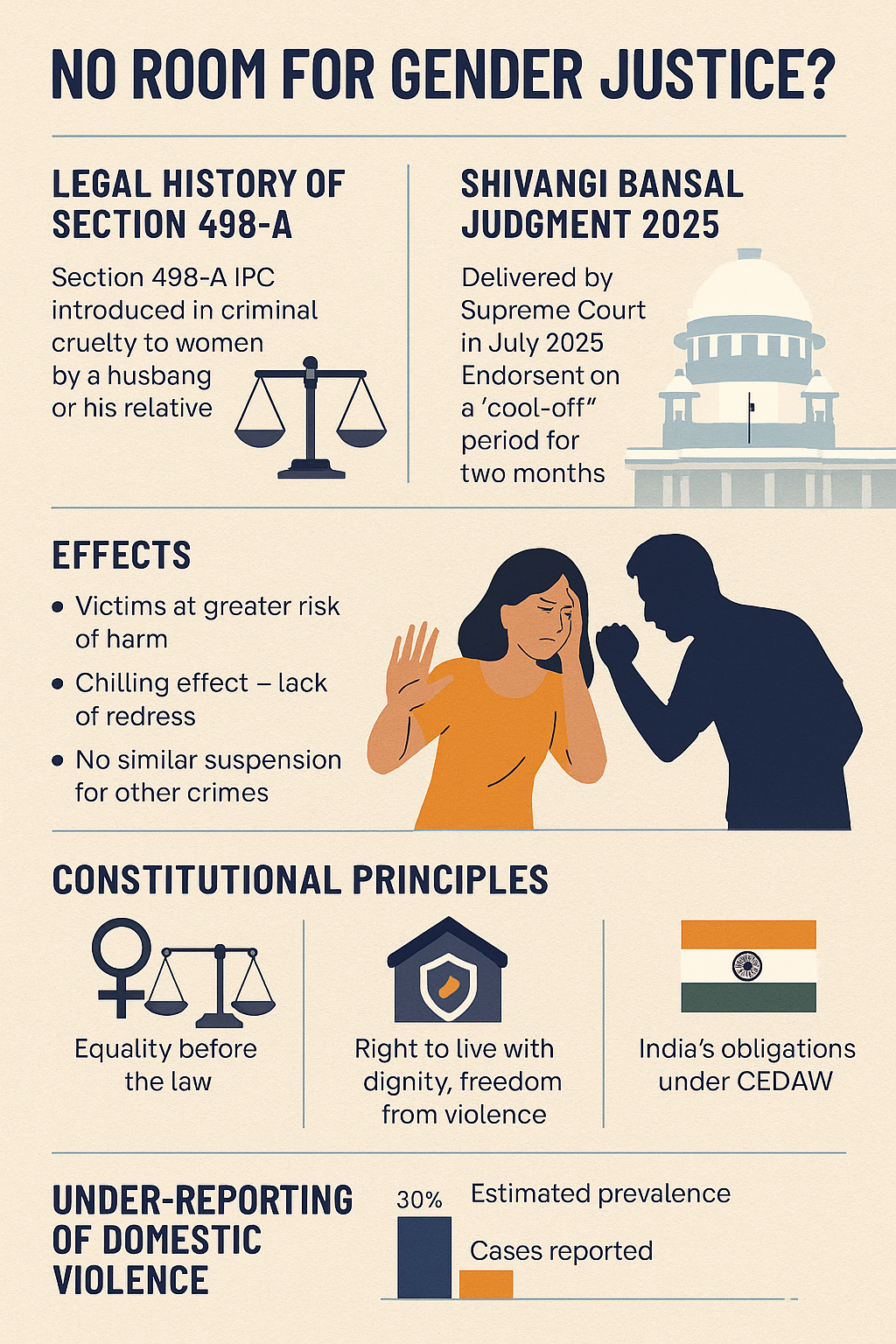

The Supreme Court of India’s ruling in Shivangi Bansal v. Sahib Bansal (July 2025) has rekindled the debate on gender justice, domestic violence legislation, and the judiciary’s function in reconciling legislative intent with alleged abuse of such laws.

The top court’s endorsement of a temporary suspension of arrest and coercive measures under Section 498-A of the former Indian Penal Code (IPC), now Section 85 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), has elicited significant concerns regarding the safeguarding of victims of marital abuse. The verdict exemplifies judicial intrusion into legislative policy, potentially jeopardising decades of legal change designed to address domestic violence and dowry-related offences.

Section 498-A IPC: Legislative Background and Socio-Legal Context

- Enacted in 1983, Section 498-A IPC was a legislative measure addressing the alarming increase in dowry-related fatalities and domestic violence incidents.

- The Statement of Objects and Reasons accompanying the amending Act emphasised the pressing necessity to criminalise all manifestations of cruelty inside marriage, broadly defining “cruelty” to include:

-

- Dowry-related harassment

- Actions driving a woman to suicide

- Actions resulting in severe harm to life or health

- This provision was crafted by Parliament to function with other protective legislation, such as the Dowry Prohibition Act of 1961, acknowledging the socio-cultural realities in which women frequently encounter structural injustice, harassment, and abuse in marital households.

Allahabad High Court’s Directions and Supreme Court Endorsement

- The origin of the present debate is rooted in the Allahabad High Court’s directive, which mandated that:

- No arrests or coercive measures shall be implemented during a two-month “cool-off“ period following the submission of a complaint under Section 498-A.

- Family Welfare Committees shall be established at the district level to evaluate situations before any subsequent police action.

- The Supreme Court’s approval of these directives, within the framework of a personal matrimonial conflict, effectively established a comprehensive safeguard for accused individuals, obstructing immediate arrests despite the presence of substantial proof of cruelty.

- Significantly, the Supreme Court:

-

- A comprehensive socio-political impact analysis of the suspension was not conducted.

- Seemed to disregard the State government’s complete details before sanctioning the order.

- The outcome: a legally binding precedent postponing police action in all similar cases for a minimum of two months, jeopardising the safety of complainants and undermining the law’s deterrent effect.

Impact on Victims and the Justice System

This court-mandated delay has significant ramifications:

- Increased Vulnerability: Victims may encounter retaliation, intimidation, or more harm within the two-month period.

- Chilling Effect: Women, already deterred from lodging complaints owing to societal stigma, may now experience additional discouragement.

- The legitimisation of police inaction: The verdict jeopardises the normalisation of delays and inaction regarding severe complaints related to “issues within marriage.”

The Misuse Narrative: Judicial History and Critique

The Supreme Court’s concerns are based on previous pronouncements:

- Sushil Kumar Sharma v. Union of India (2005): Cautioned against “legal terrorism” through the abuse of Section 498-A.

- Preeti Gupta v. State of Jharkhand (2010): Highlighted occurrences of non-bona fide allegations.

- Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar (2014): Established rigorous pre-arrest directives according to Section 41 of the CrPC.

- Although these judgments indicated apprehension regarding frivolous litigation, there is a lack of factual data demonstrating extensive misuse. The Court’s decisions have frequently been based on anecdotal judicial experience instead of thorough statistical investigation.

Criminal Jurisprudence and Legislative Competence

- From a jurisprudential perspective, criminal law provisions are formulated by the legislature to mitigate certain evils.

- In Sushil Kumar Sharma (2005), the Supreme Court determined that misuse does not constitute a valid reason to invalidate a law.

- Judicial intervention in the enforcement process, particularly on criminal statutes, should be approached with caution, especially in socially sensitive domains where institutional expertise is constrained.

- The separation of powers necessitates that:

-

- The Parliament establishes legislative policy informed by socio-legal research.

- Judicial bodies construe and implement these stipulations within constitutional boundaries.

-

- The Court jeopardises this balance by enacting a blanket suspension absent a legislative requirement.

Statistical Evidence and Ground Reality

- In contrast to the “misuse” narrative:

-

- NCRB 2022 Report Data: 134,506 cases reported under Section 498-A; conviction rate approximately 18%. This rate, although described as “low,” exceeds that of several other offences.

- The National Family Health Survey-5 indicates significant under-reporting of domestic violence, implying that the true frequency is considerably greater.

- Humsafar Centre Report: Increasing case numbers indicate heightened awareness, rather than misuse.

- The low conviction rate can be ascribed to:

-

- Familial coercion on victims to withdraw their allegations.

- Obstacles in establishing intimate partner violence beyond a reasonable doubt.

- Family members’ hesitance to provide testimony in public court proceedings.

Shivangi Bansal v. Sahib Bansal Case Developments

In the case of Shivangi Bansal v. Sahib Bansal:

- The controversy arose from a marriage conflict; nonetheless, the Supreme Court’s ruling established a precedent impacting all 498-A cases.

- The Court implemented the High Court’s “cool-off” period and the Family Welfare Committee review framework.

- A thorough assessment of potential detriments to complainants was not conducted.

- This indicates a wider judicial trend of “tempering” criminal laws designed to safeguard women, lacking sufficient socio-legal grounds to warrant such action.

Broader Constitutional and Human Rights Implications

The ruling elicits apprehensions regarding:

- Article 14 (Equality before the law): Victims of domestic violence are afforded different treatment compared to victims of other offences.

- Article 21 (Right to life and personal liberty): Safeguarding against violence in marriage constitutes an aspect of the right to live with dignity.

- India’s obligations under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women necessitate robust legislative safeguards against domestic abuse.

- The Court’s establishment of a special procedural obstacle for a specific category of victims jeopardises both constitutional protections and international obligations.

Way Forward

- The Shivangi Bansal ruling signifies a troubling alteration in the judiciary’s stance on gender-based violence.

- Although the necessity to prevent the misuse of laws is legitimate, it must not compromise victim protection or the integrity of the legislative aim.

- Criminal jurisprudence necessitates evidence-based reform rather than arbitrary suspension.

- In a nation where domestic abuse is prevalent and inadequately reported, the verdict threatens to perpetuate systemic obstacles to justice, rendering the assurance of legal equality for women increasingly superficial.

A Choice Before India: Rule of Law or Ru...

A Choice Before India: Rule of Law or Ru...

The Right to Speedy Trial Under Article ...

The Right to Speedy Trial Under Article ...

Making Forest Conservation Work for Fore...

Making Forest Conservation Work for Fore...