Table of Contents

The Indian Constitution has been regarded as a significant document, embodying the ambitions of a newly independent country. Although Dr. B. R. Ambedkar’s name is commonly linked to its creation, a thorough analysis uncovers a more intricate and varied background. This article critically examines the contributions of key figures, specifically Jawaharlal Nehru, B. N. Rau, and Ambedkar, in the drafting of the Indian Constitution. It also examines how political, legal, and religious influences have constructed a prevailing narrative that reduces this multifaceted process to a simple attribution.

The Constituent Assembly: Origins and Structure

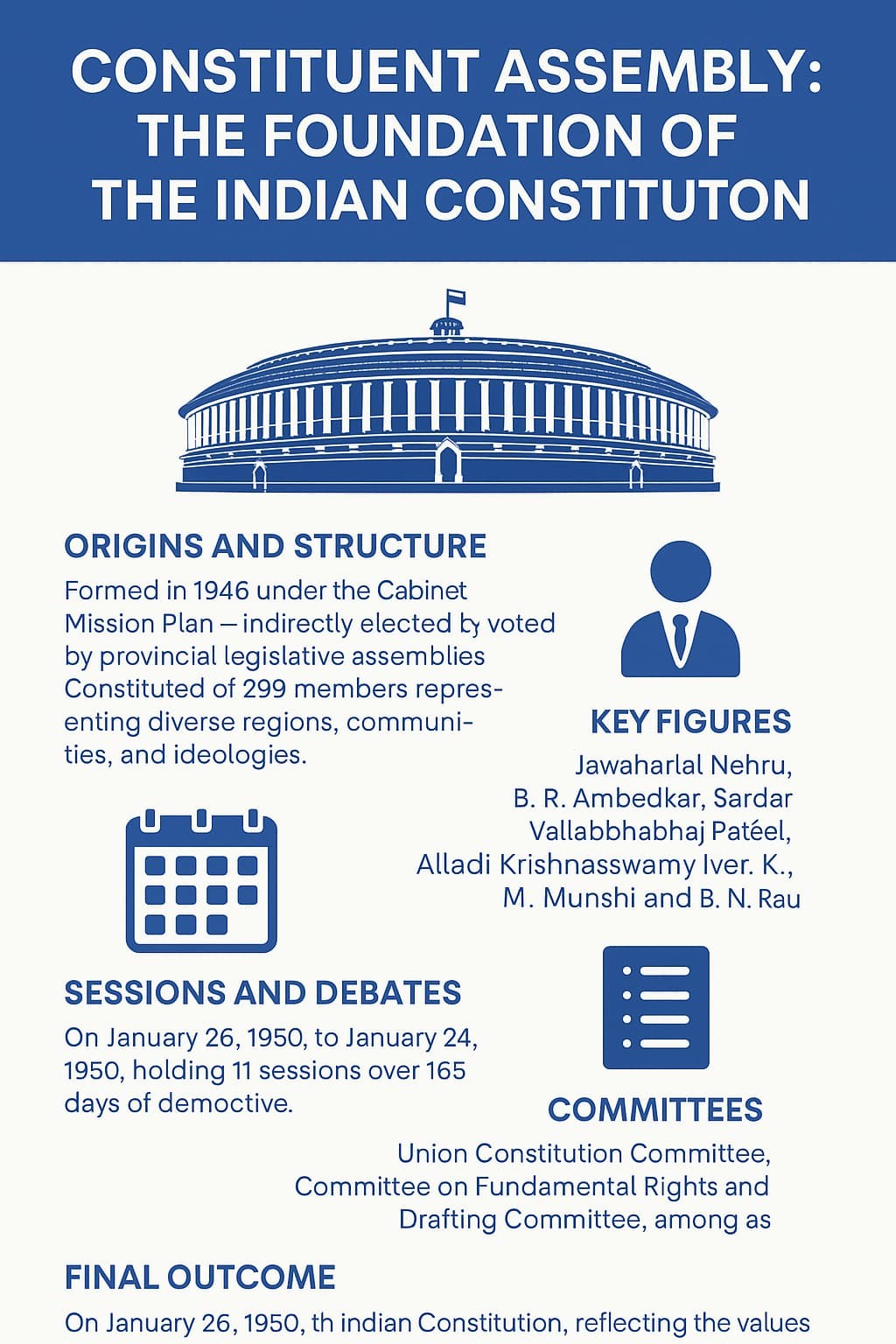

- The Indian Constituent Assembly was established under the Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946, following prolonged discussions between the British Government, the Indian National Congress, and the Muslim League.

- Although it was established before India’s actual independence, it was assigned the responsibility of drafting a constitution for a sovereign, democratic country.

- The Assembly consisted of 299 members, elected indirectly by the provincial legislative assemblies.

- These members represented a variety of regions, communities, and ideological perspectives.

- Notable individuals included Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Alladi Krishnaswamy Iyer, K. M. Munshi, and B. N. Rau, who, although not a member, acted as Constitutional Adviser.

- The Assembly functioned from December 9, 1946, to January 24, 1950, conducting 11 sessions over the course of 165 days of deliberation.

- It functioned through several committees, including the Union Constitution Committee, the Committee on Fundamental Rights, and the Drafting Committee, among others.

Nehru and British Influence on the Indian Constitution

- Jawaharlal Nehru, appointed as Vice-President of the Viceroy’s Executive Council in September 1946, significantly influenced the initial constitutional proceedings.

- The “Objectives Resolution,” proposed on December 13, 1946, established the foundational philosophy of the Constitution and highlighted India’s pursuit of sovereignty, democracy, and justice.

- Nehru recognised the limitations imposed by the British authority. In the same address, he asserted: “The British Government has a hand in [the Constituent Assembly’s] birth. They have attached certain conditions. We accepted the State Paper … and we shall endeavour to work within its limits.”

- This candid admission indicates that the Assembly was not quite devoid of colonial influence.

- Nehru’s Cambridge education and political astuteness established him as a crucial link between British expectations and Indian nationalist ambitions.

- His appointment to a prominent position before independence has prompted historical investigations regarding whether pragmatism or political ambition was his primary motivation.

Role of B. N. Rau: Architect Behind the Scenes

- B. N. Rau, a prominent ICS officer and constitutional scholar, was appointed as the Constitutional Adviser in 1946.

- Rau, influenced by British legal and intellectual traditions, composed the initial draft of the Constitution through a comparative examination of international constitutional systems, notably those of the United States, Canada, Ireland, and Australia.

- Rau’s draft constituted the fundamental document subsequently altered by the Drafting Committee, led by Ambedkar.

- Notwithstanding his pivotal achievements, Rau stayed absent from the political limelight, and his name progressively diminished from public consciousness, eclipsed by more politically famous individuals.

Nehruvian Secularism and Minority Appeasement

- The Nehru-Patel conception of secularism, articulated in Articles 25 to 30 of the Constitution, has faced criticism for favouring minority rights at the expense of equal citizenship.

- These rules confer upon minorities the autonomy to administer religious institutions, safeguard cultural heritage, and create educational establishments.

- Nonetheless, similar safeguards are not explicitly afforded to Hindus, resulting in allegations of pseudo-secularism.

- In 1948, Constituent Assembly member Damodar Swarup Seth cautioned that this methodology jeopardised secularism and had the potential to disrupt national unity.

- The constitutional framework, particularly the absence of a Uniform Civil Code and the provision of selective rights to minorities, perpetuates discussions on whether Nehru’s secularism aimed for genuine inclusivity or merely political appeasement.

The Rise of the Ambedkar-Centric Narrative

- Although Ambedkar’s achievements as Chairman of the Drafting Committee and Minister of Law and Justice are indisputable, excessive emphasis on his position has skewed the collaborative effort that resulted in the creation of the Constitution.

- The elevation of Ambedkar as the “sole architect” resulted from a combination of political strategy, social symbolism, and identity politics.

- Under Nehru, Congress embraced this narrative to mitigate criticism of the Assembly’s weak representativeness and to reinforce its minority-focused secular worldview.

- The designation “Drafting Committee,” sometimes misinterpreted as the exclusive entity tasked with composing the Constitution, perpetuated this misconception, notwithstanding its true function of enhancing Rau’s draft.

Judiciary and the Ambedkar Legacy

- The judiciary has played a crucial role in solidifying the Ambedkar-centric narrative.

- The setting up of Ambedkar’s statues in the Supreme Court (1980) and several High Courts, coupled with recurrent references to him as the “architect” in Constitution Day addresses, has conferred legal legitimacy to a reductive historical perspective.

- Judgments like Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992) and Ashoka Kumar Thakur v. Union of India (2008) reference Ambedkar’s thoughts and vision as definitive interpretations of constitutional equality and social justice.

- Simultaneously, historical materials, including Ambedkar’s 1953 Rajya Sabha address in which he referred to himself as only a “hack,” remain hidden in mainstream legal culture.

Political Symbolism and Popular Culture

- Political parties from all ideological backgrounds, both secular and Hindutva proponents, have utilised Ambedkar’s image for electoral advantage.

- The extensive erection of sculptures, designation of highways, establishment of institutions, and media representations, like the 2000 film Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, have rendered him the symbolic figure of the Constitution.

- These techniques exert simultaneously, eclipsing the contributions of figures such as Nehru and Rau.

- The 2005 Gwalior Bench incident, characterised by violent protests against the Ambedkar statue within a court enclosure, exemplifies the significant emotional investment associated with this emblematic supremacy.

Reclaiming Historical Accuracy: Satyameva Jayate

- India’s national motto, Satyameva Jayate (Truth Alone Triumphs), advocates for adherence to historical truth.

- Correcting the Ambedkar-centric narrative does not undermine his significance; instead, it reinstates appropriate recognition to the wider community that shaped India’s constitutional character.

- Proposed Reforms:

-

- Legal and academic curriculum should integrate primary materials, such as Rau’s papers and Assembly Debates.

- The phrase “Drafting Committee“ must be accurately contextualised in public discourse.

- The judiciary and politicians ought to embrace a balanced narrative that recognises various contributors.

- Priority should be given to improving archival accessibility and the release of primary materials.

- The Indian Constitution is not the work of a single individual but the synthesis of various intellects- Nehru’s political acumen, Rau’s constitutional expertise, and Ambedkar’s reformist perspective.

- A developed democracy must address myths with evidence, emotions with research, and symbolism with reality.

- Only then can India genuinely represent the essence of Satyameva Jayate and uphold the shared heritage of its constitutional progenitors.

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...