Table of Contents

Context: This article seeks to examine Article 143 of the Constitution of India, while also highlighting recent developments associated with it.

Why in News?

On 22nd July 2025, the Supreme Court of India began significant proceedings following a Presidential Reference made under Article 143 of the Constitution. The reference, initiated by President Droupadi Murmu, seeks constitutional clarification on the powers and duties of the Governors and the President in granting assent to bills passed by the State Legislature. It specifically inquires whether courts have the authority to set binding timelines for such assent when the Constitution is silent on the point.

A Constitution Bench headed by Chief Justice B.R. Gavai, along with Justices Surya Kant, Vikram Nath, P.S. Narasimha, and A.S. Chandurkar, announced that comprehensive hearings are set to commence in mid-August. The case is scheduled for more instructions on July 29, at which point the court will finalise the schedule for the extensive hearing.

In a move to ensure a comprehensive examination of the matter, the Supreme Court has issued formal notices to both the Union Government and all State Governments, indicating the importance of this Constitutional inquiry and its possible effects on the legislative process in the country.

Presidential Reference: Background

On 13 May 2025, President Droupadi Murmu invoked the Supreme Court’s advisory power under Article 143 of the Constitution. This allows the President to ask the Court for its view on important legal or factual issues. She referred to 14 questions about the powers of a Governor and the President, based on Articles 200 and 201. This came after a Supreme Court ruling in the case of State of Tamil Nadu v. Governor of Tamil Nadu (2025). In that case, the Court had set time limits for the Governor and President when bills are sent to them for approval.

The Tamil Nadu Governor Judgment

On 31 October 2023, the Tamil Nadu government took a major action by raising concerns about Governor R. N. Ravi’s ongoing delay in giving his approval to 10 bills that were passed by the state government. Between November 2020 and April 2023, the state legislature passed 13 bills, but 10 of them were either sent back to the Assembly by the governor or remained pending without a clear reason.

Even though the Assembly passed these bills again without altering their content, the governor did not approve them but instead forwarded them to the President. As a result, the Tamil Nadu government filed a writ petition challenging the governor’s continued refusal to give assent to these important bills.

On April 8, 2025, the Supreme Court bench composed of Justices J.B. Pardiwala and R. Mahadevan ruled that the Governor’s indefinite delay in not approving state legislative bills was “illegal” and “erroneous”. The court explained that under Article 200 of the Constitution, the Governor has only three choices: approve the bill, reject it, or send it to the President for decision.

Additionally, if a bill was passed again by the state assembly after the Governor initially rejected it, the Governor was required to approve it. The court also stated that the Governor could not use a complete veto to block the bill permanently.

The Bench invoked the Court’s inherent authority under Article 142 to consider ten pending state bills as having received assent. By “deeming assent,” the judgment rendered any action taken by the President on the reserved bills invalid. As a result, this effectively nullified the President’s decision to approve one of the bills.

The Bench set clear time limits for the Governor and the President to act on bills they receive. The bench also clarified that setting a timeline does not amend the Constitution but reinforces the urgency intended by Article 200. This timeline acts as a guideline, with inaction subject to judicial review, compelling the Governor to justify any delays in granting assent. It prevents the Governor from exercising a pocket veto over bills. The state governments can ask the courts for a mandamus order if those time limits are not followed. A mandamus order is a court directive that tells a government official to carry out their legal duties.

The Court prescribed the following timelines, relying on the decision in Keisham Meghachandra Singh v Speaker, Manipur Legislative Assembly (2020), where a limit was prescribed for the Speaker to decide disqualification petitions:

| Action | What Must Happen |

| If the Governor withholds assent or reserves the bill for the President, on the aid and advice of the Council of Ministers | Sent back to Legislature in one month |

| Governor withholds assent contrary to the advice of the Council of Ministers | Sent back to Legislature in three months |

| Governor reserves the Bill for the President contrary to advice of the Council of Ministers | Reserve bill within three months |

| If the Legislature re-passes and re-presents the Bill | Assent within one month |

Timeline for President

Under Article 201, the President has two choices: either grant or withhold assent. If the President withholds assent, she can send it back to the state legislature through the Governor, along with a note explaining her recommendations. The legislature then has six months to review the bill again. If they pass it again, either as it was or with changes, it goes back to the President for her final decision.

The court ruled that the President cannot withhold assent without giving reasons. The Constitution does not allow for an absolute veto. The President may withhold assent only for those bills that specifically fall under constitutional provisions requiring her assent. However, unlike the Governor, the President is not obligated by the Constitution to assent a bill that has been reconsidered by the legislature.

The Court laid down a three-month deadline for Presidential approval of bills which were reserved for her consideration.

What is Article 143?

Origin

In India, the idea of advisory jurisdiction came from the Government of India Act, 1935. Section 213 of this act provided that if the Governor-General believed a situation had happened or might happen where a question of fact or law could arise, he could ask the federal court for advice on that matter. The federal court was allowed to handle these matters as it saw fit and give the Governor-General a proper recommendation.

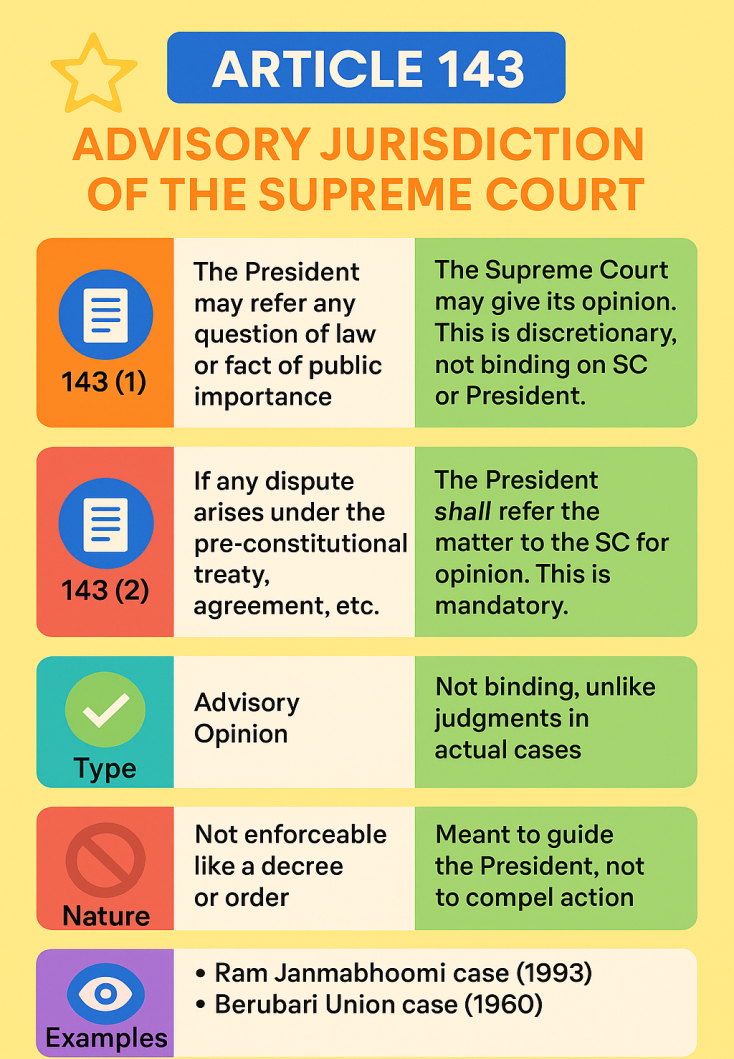

- According to 143(1), when it appears to the President that a question of law or fact has arisen or is likely to arise, which is of such a nature and such public importance, that it is ‘expedient’ to obtain the opinion of the Supreme Court upon it, he may refer it to the Court for its consideration.

- The Court then may, after such hearing as it thinks fit, report to the President its opinion thereon.

The use of the word ‘may’ in Article 143(1) of the Constitution shows that the Supreme Court is not bound to give an advisory opinion in every reference made to it. The Supreme Court may refuse to give its advisory opinion for strong, compelling and good reasons.

- Article 143(2) allows the President to refer disputes arising from any pre-constitution treaty, agreement, covenant, sanad or other similar instruments. The SC shall tender its opinion to the President.

- A report under the above provisions is to be made by the Court in accordance with an opinion delivered in open court [Art. 145(4)] with the concurrence of the majority of Judges [Art. 145(5)].

- A Judge who does not concur has liberty to deliver a dissenting opinion [Art. 145(4)].

- The reference is to be heard by a Bench of not less than five Judges [Art. 145(3)]. Thus, the procedure in respect of the exercise of the advisory jurisdiction has, as far as possible, been approximated to a judicial hearing.

Article 74(1) requires the President to act based on the guidance and advice of the Council of Ministers. Consequently, while the reference may officially come from the President, it is essentially made by the Council of Ministers. However, the Supreme Court is unable to verify whether the reference originates with the President or is based on the council’s advice, due to the constitutional limitation outlined in Article 74(2). If the President consults the Supreme Court under Article 143 without counsel from the council of ministers, it would constitute a breach of the Constitution, potentially leading to impeachment.

Is the Supreme Court Obligated to Respond to a Presidential Reference?

The Supreme Court has the authority to decline to give an advisory opinion if it believes that doing so is inappropriate based on other pertinent facts and circumstances. This may occur, for example, if the questions posed are solely socio-economic or political and do not pertain to constitutional matters. Essentially, the Court can either choose to respond to the reference or respectfully choose not to submit a report to the President.

In the case of the Kerala Education Bill, 1957, the Supreme Court stated that it is required to consider a reference and provide its opinion to the President if the reference falls under Article 143(2). However, under Article 143(1), the Court has the discretion to decline to express an opinion on the submitted questions if there are valid reasons to do so.

The insights provided in the Special Courts Bill (1978) were noteworthy for several reasons. It stipulated that the court may opt not to respond to a reference, that the questions presented must be clear and specific rather than vague, and that, in addressing a reference, the court should refrain from encroaching upon the functions and privileges of Parliament.

Nevertheless, among all the references made so far, the court has only chosen not to provide an opinion for one case, which was in 1993 regarding the Ram Janmabhoomi issue.

Since 1950, there have been approximately fifteen references made before the current one. Some key opinions from these landmark references are provided below:

- Delhi Laws Act case (1951): This case explained what delegated legislation can do.

- Kerala Education Bill (1958): This case showed how Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles can work together.

- Berubari case (1960): The court said that changing territory needs a constitutional amendment.

- Keshav Singh case (1965): This case talked about the privileges of the legislature.

- Presidential poll case (1974): The court allowed elections even if some State Assemblies were empty.

- Third Judges case (1998): This case created the Collegium system for appointing judges.

- 1993 Ram Janmabhoomi Case / 1994 Ismail Faruqui Case: The court refused to answer the reference, showing its ability to decide not to give advisory opinions when the questions don’t have legal or practical importance and are politically sensitive.

- Natural Resources Allocation Case (2012): The Supreme Court supported the 2G verdict but also said that auctions aren’t the only way to allocate natural resources if there is a valid reason.

Key issues in the current reference include whether courts can set time limits for the President and Governors to act, even if those timelines are not mentioned in the Constitution, especially under Articles 200 and 201. It also brings up questions about the limits of the Supreme Court’s power under Article 142, which allows the Court to ensure complete justice.

The current reference has posed 14 questions, mainly focused on the interpretation of Articles 200 and 201, for the court to address. Additionally, it has questioned whether the actions of Governors and the President can be subject to judicial review before a Bill is enacted into law.

Constitutional Provisions in Question

Article 200: Governs Governor’s assent, withholding, or reserving Bills; no prescribed time limit for action.

Article 201: Governs President’s assent/withholding of Bills reserved by Governor; no time frame specified.

Article 361: Grants immunity to President and Governors from legal action during office, raising questions on judicial review limits.

Article 142: Grants SC power to do “complete justice” but its scope, whether procedural only or overriding substantive constitutional provisions, is contested.

Article 145(3): Prescribes a minimum five-judge Bench for substantial constitutional questions, challenged by two-judge Bench rulings.

Article 131: SC’s original jurisdiction in Centre-State disputes, questioned for its scope in recent cases.

Scope and Limitations of Advisory Opinions

No Overruling of Final Judgments: Presidential reference cannot nullify or override a judgment that has become final.

Legal Clarifications Allowed: The court can use its advisory power to explain or improve the legal rules set out in a final judgment, without making the judgment invalid.

Advisory Opinion Binding or not?

The advisory role of the Supreme Court differs from its regular judicial function in three ways: First, there is no dispute between the two parties involved; Second, the Court’s advisory opinion is not binding on the government; and Third, it cannot be enforced like a regular court judgment.

Seeking an advisory opinion from the Supreme Court helps the executive make better decisions on major issues.

It also provides the Indian government with a less confrontational way to handle some politically challenging matters. The marginal note of Article 143 states, “Power of President to Consult Supreme Court. The word “consult” clearly shows that the President is not required to follow the Court’s opinion.

Moreover, an advisory opinion cannot be enforced. Therefore, judgments given under Article 143 are not as binding as those issued under Article 141. Though opinion is not legally binding but is treated with high moral and legal respect.

Conclusion

As the Supreme Court considers the crucial constitutional issues presented by President Murmu, the decision will not only influence the interpretation of executive powers but also establish a precedent for future constitutional analysis in India. This significant reference under Article 143(1) underscores the ongoing relationship between the Executive and the Judiciary, with the potential to alter the distribution of power within the nation’s legal system. As the country anticipates the Court’s ruling, the implications are significant, and resolving these matters will undoubtedly affect the operation of India’s democratic institutions for years to come.

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...