Table of Contents

The law does not serve as a solution for every moral or ethical wrong. Human behaviour frequently includes activities that may be ethically questionable yet legally permissible. For example, ingratitude, dishonesty in interpersonal relationships, and indifference to the suffering of others constitute moral flaws yet do not qualify as criminal offences. A Bad Samaritan cannot face prosecution only for a lack of assistance unless a particular legal obligation is present. Consequently, law and morality represent separate realms.

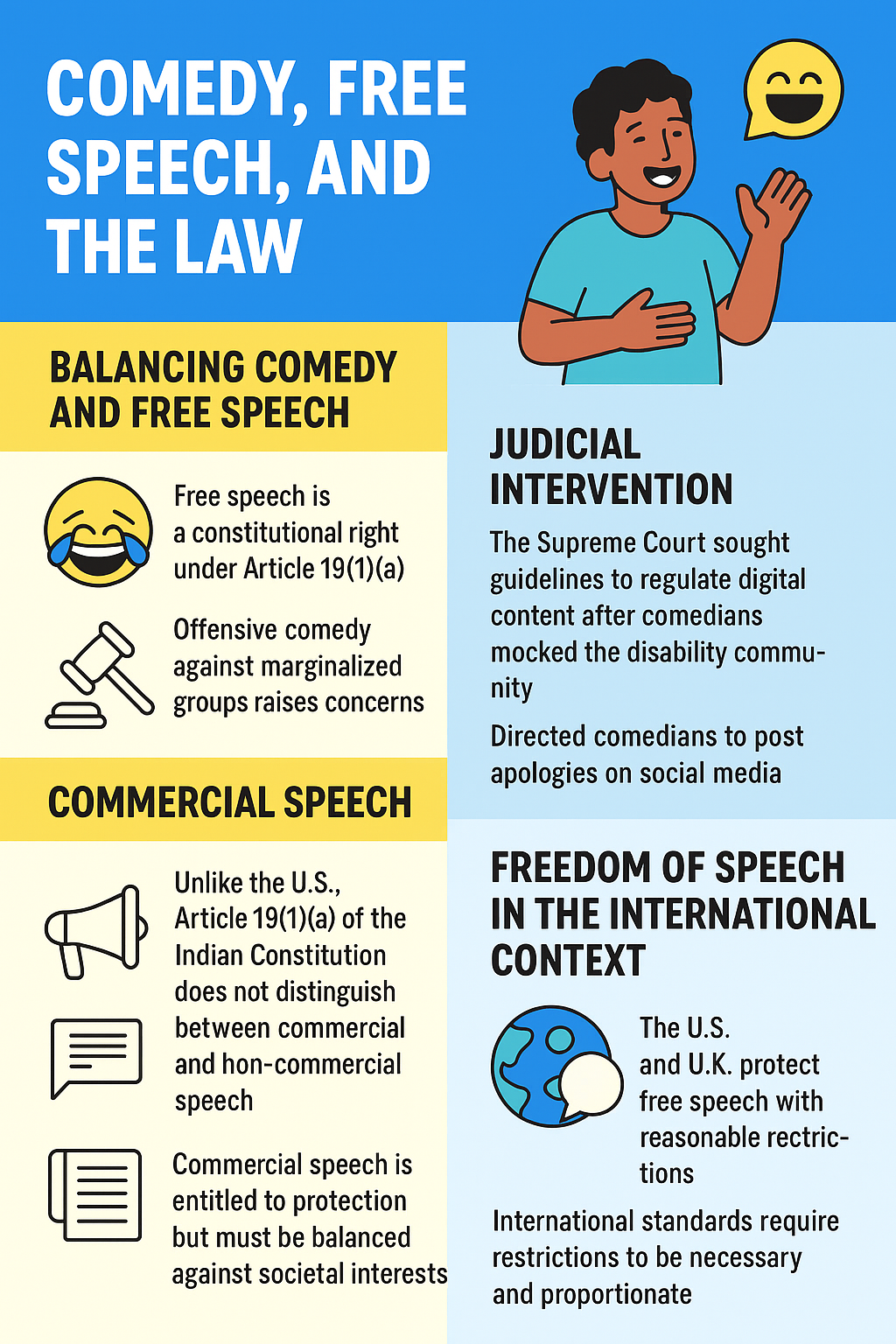

Nonetheless, regarding freedom of speech and expression, the implications are far greater as this issue pertains to a basic right enshrined in Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India. Any limitation on this freedom must precisely adhere to the “reasonable restrictions” specified in Article 19(2), which is subject to judicial review.

Comedy, Freedom of Expression, and Judicial Supervision

- Comedy frequently functions as social critique. The conflict between comedy and offence gets problematic when jokes target marginalised communities or are disseminated via social media channels.

- The Supreme Court of India recently, during the consideration of a petition submitted by YouTuber Ranveer Allahbadia, advocated for the establishment of norms governing digital material following many legal actions against him.

- Subsequently, the Court mandated that five comedians charged with mocking those with disabilities issue public apologies.

- It moreover proposed the necessity to govern social media speech and outline the distinction between “free speech” and “hurtful speech.” The Attorney General proposed to develop a framework, incorporating contributions from the Bar and other stakeholders.

- This judicial emphasis on stringent rules prompts apprehensions regarding the separation of powers. Montesquieu’s principle asserts that only the legislature has the authority to enact laws.

- Judicial directives compelling the executive to establish regulations pose a significant risk of overreach, potentially destabilizing the constitutional equilibrium of powers.

Commercial Speech and Freedom of Expression

- A distinctive aspect of the Court’s recent remarks is the focus on “commercial speech.” The First Amendment in the United States provides restricted protection to commercial speech in contrast to political or social expression.

- In India, Article 19(1)(a) does not differentiate between commercial and non-commercial speech. Judicial interpretation has delineated its boundaries:

- Hamdard Dawakhana v. Union of India (1959)– The Court determined that commercial ads, particularly those endorsing harmful substances, do not qualify for protection under free speech.

- Indian Express Newspapers v. Union of India (1984). The Court acknowledged that limiting advertisements in newspapers impacted circulation and thereby infringed upon Article 19(1)(a).

- Tata Press Ltd. v. Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd. (1995) The Court specifically determined that commercial speech constitutes a component of Article 19(1)(a), as it conveys information advantageous to consumers.

- Suresh v. State of Tamil Nadu (1996)– The Court underscored the necessity of reconciling business interests with societal welfare in the assessment of speech claims.

- These rulings underscore that although commercial speech is constitutionally protected, its extent is contingent upon context and societal interest.

Freedom of Expression and Social Media in India

- The digital era has fundamentally altered the distribution of speech.

- Social media platforms enhance expression while simultaneously exacerbating the dangers of hate speech, misinformation, and the mockery of marginalised communities.

- The Supreme Court’s rulings in the comedians’ case indicate an increasing apprehension regarding the regulation of such expression.

- Nonetheless, court-ordered regulation poses a risk of devolving into censorship, particularly when ambiguous classifications like “hurtful speech” are employed.

- Article 19(2) delineates explicit grounds for restriction, including public order, decency, morality, defamation, and state security. Extending these boundaries via court directives may render the assurance under Article 19(1)(a) ineffective.

Relevant Cases on Free Speech and Digital Expression

- Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015). The Court invalidated Section 66A of the IT Act due to its vagueness and its suppressive effect on online free speech.

- Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram (1989) Free expression may only be curtailed if there exists a “proximate and direct nexus” to public disorder.

- Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India (2020)– It was determined that an internet connection is essential to free speech as per Article 19(1)(a).

- Kaushal Kishor v. State of Uttar Pradesh (2023)– The Court determined that the right to free speech under Article 19(1)(a) may be invoked against non-State actors under specific conditions.

- These rulings collectively underscore the necessity of comprehensive protection for free speech, with limits requiring precise limitations.

Unrestricted Expression in the Global Context

- Worldwide, freedom of speech is acknowledged as a fundamental democratic principle:

- The First Amendment of the United States offers robust protection for free speech, encompassing offensive comments, with limited exceptions for obscenity or incitement. Commercial speech, meanwhile, receives limited protection.

- The United Kingdom safeguards freedom of expression under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), albeit with extensive proportionality-based limitations.

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Article 19: Safeguards the right to free expression, permitting limits solely for the protection of others’ rights/reputation, national security, public order, or public health/morals. As a signatory, India is obligated to fulfil these commitments.

- The UN Human Rights Committee (General Comment No. 34, 2011) underscored that limitations on free speech must be strictly essential and proportionate.

- The global trend favours limited control of free speech, extending protection even to controversial or unpopular opinions, unless they constitute hate speech or incitement.

Concluding Remarks

- The convergence of comedy, free expression, and legislation in India underscores a multifaceted quandary.

- Although inappropriate comedy directed at marginalised groups necessitates ethical caution, the resolution may reside more in social and cultural responses than in stringent legal regulation.

- Judicial directives requiring legislation to regulate speech may exceed constitutional limits and compromise Article 19(1)(a).

- The acknowledgement of commercial speech as a facet of free expression adds complexity to the environment.

- A careful balance is necessary between safeguarding individual dignity and maintaining democratic liberties.

- India must be cognizant of international standards that advocate for comprehensive free speech protections.

- The resolution of this argument necessitates both constitutional adherence and a sophisticated understanding of the functions of comedy, dissent, and internet platforms within a democratic society.

Faster Is Not Fairer: Reassessing POCSO ...

Faster Is Not Fairer: Reassessing POCSO ...

Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988: Evol...

Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988: Evol...

The Securities Markets Code, 2025: Conso...

The Securities Markets Code, 2025: Conso...