Table of Contents

Why in the news?

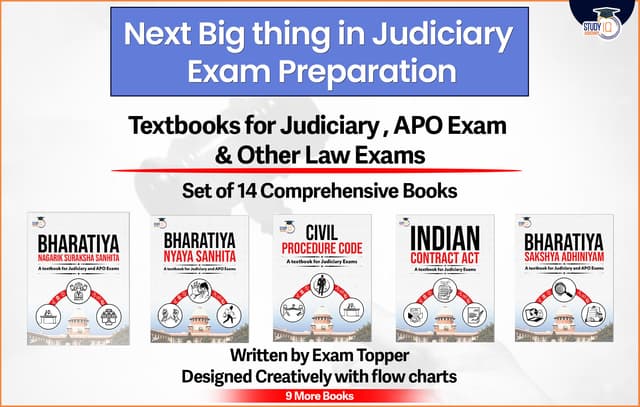

The Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC) has been replaced by the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS). As of July 1, 2025, Section 124A IPC, which criminalized sedition, is no longer in effect, marking an end to a colonial-era suppression tool. The BNS introduces a new provision (Section 152 BNS, subject to final numbering) that criminalizes acts endangering India’s sovereignty, unity, or integrity.

Critics Argument

Critics argue this is essentially “old wine in a new bottle,” as it broadens the scope for restricting free speech. Although the Supreme Court had stayed the old sedition law in May 2022, petitioners contend that the new provisions may still be unconstitutional, keeping legal challenges alive.

Recent FIRs under the new “sovereignty” provision have raised alarms. For instance, activists in Nagpur faced legal action for reciting a revolutionary poem, leading to concerns about the potential misuse of this law to suppress dissent. The 22nd Law Commission recommended retaining sedition with stricter definitions, arguing that national security demands such measures, which is reflected in the BNS.

Journalists and human rights groups contend that the new law infringes on Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution, while the government defends it as essential to protect India from misinformation and separatism, particularly in the digital era.

Sedition Law in India: Introduction

For over a hundred years, Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, which criminalized sedition, stood as a stark reminder of India’s colonial past. Originally introduced by the British colonial regime, the provision was designed to suppress nationalist uprisings and silence influential voices such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi. Although the British left, the law remained, evolving into a contentious instrument used by successive Indian governments to curb dissent, manage separatist rhetoric, or stifle political opposition.

In a significant legislative shift, the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS) repealed this colonial-era sedition law. However, this move has not ended the debate it has merely transformed it. Legal scholars and civil society actors now question whether sedition has truly been abolished or simply rebranded under a different legal framework.

Historical Background of Sedition Law

Historically, sedition laws were introduced during British rule to suppress rebellion against the colonial government. In simple terms, sedition refers to acts that incite people to rebel against lawful authority.

Over time, both before and after Independence, this law has been used by the State to silence citizens who raised their voices against the government. Recognizing the potential for misuse, Indian courts have often intervened to limit the law’s reach. Even during colonial times, the judiciary attempted to temper its application.

In the landmark case of Niharendu Dutt Majumdar v. Emperor, MANU/WB/0224/1939, the court held that sedition must involve some form of incitement to lawlessness or violence. Mere criticism, without any such consequence, would not amount to sedition. This interpretation laid the groundwork for a more restrained application of the law.

Post-Independence

Post-Independence, the judiciary continued to play a crucial role in safeguarding civil liberties. In recent years, the Supreme Court has taken proactive steps to examine the constitutional validity of sedition, recognizing its potential to infringe upon fundamental rights. These developments reflect a broader institutional acknowledgement, both by the judiciary and the legislature, that the sedition law, in its traditional form, is incompatible with democratic values and must be reconsidered.

The core constitutional challenge to Section 124A lies in its conflict with Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees the right to freedom of speech and expression. The provision criminalized any spoken or written words, signs, or representations that brought the government into hatred or contempt, or excited disaffection against it. Critics argue that such vague and expansive language enabled the State to suppress legitimate criticism, thereby violating human rights and enabling preventive detention in some cases.

A particularly nuanced issue that has emerged in recent discourse is the distinction between the government and the State. The sedition law, as originally conceived, was aimed at protecting the ruling government, not the nation or the State as a whole. This distinction is crucial while the State represents the enduring constitutional and institutional framework of the country, the government is a temporary political entity. The colonial sedition law was designed to shield the British Crown, and its continued use in independent India raised concerns about conflating criticism of the government with disloyalty to the nation.

Interestingly, Section 124A was not part of the original IPC enacted in 1860. At that time, Section 121 addressed acts of waging war against the Queen. Sedition was introduced later, in 1870, as a distinct provision to address emerging threats such as seditious preaching and fundraising by Wahhabi reformists. This historical context reinforces the argument that the law was crafted to protect the ruling regime rather than the broader interests of the Indian State.

Thus, the sedition law functioned as a quasi-emergency provision, enabling the government to suppress perceived threats to its authority. While some may argue that governments require legal tools to maintain order and stability, such powers must be balanced against constitutional freedoms.

Sedition Law in India: Historical Background

India’s colonial past under British rule has left a deep imprint on its legal and political institutions. Even after independence in 1947, several colonial-era laws especially those designed to suppress dissent continued to shape the Indian legal landscape. Among the most contentious of these is the law on sedition.

The roots of India’s sedition law can be traced back to the early 19th century during the British Empire’s efforts to codify Indian criminal law. In 1837, Thomas Babington Macaulay, as part of the First Law Commission, drafted the Indian Penal Code (IPC), which included a provision criminalizing sedition and prescribing life imprisonment for those inciting disaffection against the government.

However, this sedition clause was omitted when the IPC was formally enacted in 1860, likely due to oversight or political caution. It wasn’t until 1870 that James Fitzjames Stephen, then Law Member of the Governor-General’s Council, formally introduced Section 124A into the IPC. This provision was modelled on the English Treason Felony Act of 1848, which criminalised attempts to undermine the authority of the Crown.

Section 124A defines sedition as any act, spoken, written, or symbolic that attempts to incite hatred, contempt, or disaffection toward the government established by law. During the colonial era, this law became a powerful tool to silence nationalist voices. It was used to prosecute prominent leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who was convicted twice under this provision for his writings in Kesari, and later Mahatma Gandhi, who famously referred to it as the “prince among the political sections of the IPC designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen.”

With independence came a renewed commitment to civil liberties, leading the Constituent Assembly to debate whether sedition had any place in a free India. Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution guaranteed freedom of speech and expression, yet the continued existence of Section 124A created a tension between colonial-era repression and democratic rights. Despite strong opposition from members like K.M. Munshi and Sardar Patel, who argued that sedition had been misused to stifle legitimate criticism, the provision was not repealed.

In 1950, the Supreme Court delivered two landmark judgments Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras and Brij Bhushan v. State of Delhi in which it held that public order was not a constitutionally valid ground to restrict free speech under Article 19(2) as it then stood. These rulings invalidated state actions that sought to suppress publications such as the RSS journal “Organiser” and the magazine “Crossroads”, which had criticized government policies.

In response, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru introduced the First Constitutional Amendment in 1951, which added “reasonable restrictions” to Article 19(2), including public order as a valid ground. This amendment effectively re-legitimized sedition law, although Nehru expressed discomfort with its colonial legacy.

A significant procedural shift occurred in 1973 when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi enacted a new Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), making Section 124A a cognizable offence. This meant that police could arrest individuals without a warrant and begin investigations without prior judicial approval, significantly expanding state power to curb dissent and having far-reaching implications for civil liberties.

The legacy of Section 124A continues to provoke debate in modern India. Critics argue that it is anachronistic, vague, and prone to misuse, especially against journalists, activists, and dissenters, while supporters contend that it is necessary to protect national integrity and sovereignty. The Supreme Court has repeatedly sought to narrow its scope most notably in Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar (1962) but the law remains on the books, awaiting either repeal or reinterpretation.

Section 152 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023

Section 152 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, criminalizes a wide range of actions that threaten India’s sovereignty, unity, and integrity. Under this provision, any person who, with deliberate intent or knowledge, uses spoken or written words, signs, visible representations, electronic communications, financial transactions, or any other means to incite or attempt to incite secession, armed rebellion, or subversive activities can be prosecuted.

The section also captures those who encourage separatist sentiments or engage in conduct that endangers the nation’s territorial or political cohesion. Conviction under Section 152 carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment, or imprisonment of up to seven years, along with a fine.

Although the word “sedition” has been removed, Section 152 inherits its spirit from Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. Sedition trials under Section 124A were effectively put on hold by the Supreme Court in May 2022, and the government pledged to repeal the colonial-era law. Yet by enacting Section 152, Parliament has preserved core elements of sedition expanding and rebranding them under a different label. In practice, this has raised concerns that the state’s power to clamp down on dissent remains intact, even after the formal repeal of Section 124A.

Compared with its predecessor, Section 152 broadens the scope of punishable conduct far beyond “hatred, contempt, or disaffection” toward the government. It explicitly targets “secession,” “armed rebellion,” and “subversive activities,” terms that lack precise legal definitions. The inclusion of modern vectors such as electronic communication and financial means further extends the state’s reach into digital speech and funding networks. This vagueness risks casting too wide a net over legitimate forms of criticism or peaceful protest, potentially chilling free expression.

Judicial scrutiny has already begun to push back against overly broad interpretations. In Tejender Pal Singh v. State of Rajasthan (2024), the Rajasthan High Court emphasized that Section 152 must not become a proxy for sedition. The court insisted on a clear and imminent link between the impugned speech or action and the likelihood of rebellion or secession. It held that vigorous but lawful criticism of government policies cannot amount to an offence unless it directly incites violence or public disorder. This decision underscores the need for courts to maintain a high threshold of proof and to protect constitutional freedoms.

When compared side by side, Section 152 of the BNS and Section 124A of the IPC reveal both continuity and expansion. While both provisions aim to safeguard the state against threats to its authority, Section 152 replaces “disaffection” with more expansive terms like “secession” and “subversion,” increases the maximum imprisonment term from three years to life, and adds electronic and financial channels to the list of prohibited modes.

The absence of precise definitions for key terms heightens the risk of arbitrary enforcement, making robust judicial guidelines essential. The preservation of national security must be balanced against the fundamental right to free speech. To prevent misuse, courts should insist on proof of imminent harm before allowing prosecutions under Section 152.

Law enforcement agencies must adhere to strict standards of evidence, and judges should continue refining the jurisprudence to clearly distinguish between protected dissent and genuine threats to the nation. Only with vigilant judicial oversight can Section 152 serve its stated purpose without undermining India’s democratic principles.

The language of Section 152 BNS, 2023 is strikingly broad, criminalizing any conduct deemed to “endanger the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India” without laying down concrete criteria for what crosses that line. In practice, this vagueness hands immense discretion to police and prosecutors, a sharply worded opinion about a public policy or an expression of sympathy for a contentious movement could be recast as sowing division and trigger legal proceedings. The absence of clear statutory definitions means that everyday statements whether in a speech, an article, or even on social media are vulnerable to being mischaracterized as threats to the nation’s cohesion.

By including the word “knowingly,” Section 152 further lowers the bar for securing arrests and prosecutions. A person need not intend to foment rebellion or carve out a separate territory; it is sufficient that they shared a message or participated in an activity while aware it might fuel separatist sentiment. This subjective test of knowledge can ensnare ordinary citizens who repost controversial content or engage in contentious debates online, exposing them to criminal liability even when their aim was simply to inform or to protest peacefully.

As section 152 is a cognizable, non-bailable offence, it poses a serious threat to the free exchange of ideas. Police can arrest suspects without a warrant and initiate investigations before any judicial review, subjecting individuals to detention and interrogation on the mere suspicion that they might undermine India’s unity. Such a mechanism inevitably chills the speech of journalists, academics, activists, and dissenters who may self-censor to avoid the risk of arrest, stifling the robust public discourse essential to a healthy democracy.

Historical data underscores the risk of misuse. Between 2015 and 2020, only 12 out of 548 people charged under the old Section 124A IPC of sedition were ultimately convicted, according to NCRB figures. The broader sweep and looser definitions in Section 152 suggest that even more people could be swept into criminal proceedings, multiplying the burden on individuals and the justice system alike.

Without meaningful checks, this provision seems primed to amplify arbitrary enforcement rather than curb genuine threats to national security. Unlike Section 124A whose excesses the courts gradually reined in through careful judgments Section 152 currently offers no built-in statutory safeguards. There are neither clear guidelines for distinguishing legitimate critique from criminal conduct nor explicit exemptions for peaceful political speech. Until the judiciary imposes firm limits, the risk remains that Section 152 will function as a catch-all for any dissent it dislikes, eroding constitutional protections for free expression.

In defending Section 152, the government insists that it marks a decisive shift from a law aimed at shielding the ruling administration to one protecting the country as a whole. They argue that, unlike IPC Section 124A which punished “disaffection” against the government, the BNS targets only conduct that genuinely threatens India’s territorial integrity or sovereignty.

Moreover, they point to the requirement of “intent” as raising the threshold for prosecution asserting that casual criticism of government policies will not suffice to trigger criminal liability. Whether these assurances will hold firm under judicial scrutiny remains to be seen.

The Supreme Court must step in to draw bright lines around Section 152’s reach, crafting detailed guidelines that leave no doubt about what behaviour truly amounts to a prosecutable offence. Much like the procedures laid down in D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal—which imposed strict requirements on arresting officers to protect individual liberty and curb arbitrary detention, the Court should mandate clear checklists for police action, require immediate notification of arrests, and insist on timely judicial review of every charge under Section 152.

By spelling out exactly when and how authorities can invoke this provision, the judiciary would safeguard citizens against capricious application while preserving the true purpose of the law: thwarting genuine threats to national cohesion.

At the same time, Parliament ought to bolster these judicial safeguards with express statutory protections in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita itself. Before any arrest under Section 152, police should be obliged to secure a magistrate’s authorization, ensuring an independent assessment of necessity.

Investigators must also demonstrate prima facie evidence that the accused’s words or actions were likely to incite secession, armed rebellion, or serious public disorder, rather than relying on vague impressions of “endangering integrity.” Embedding such prerequisites into the statute would not only limit overreach but also focus enforcement squarely on conduct that poses a real, quantifiable danger to the nation.

Preserving a robust marketplace of ideas lies at the heart of democratic self-governance, as Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes famously articulated in Abrams v. United States. Open debate, even when it strays into provocative or unpopular territory, serves as society’s ultimate filter for truth and legitimacy.

Particularly in our age of social media, where opinions cascade across networks in an instant, the law must distinguish between incendiary threats to state security and the honest airing of grievances or ideological dissent. By affirming that only speech directly linked to imminent violence or organised rebellion falls outside protected discourse, India can honour Holmes’s vision of free expression as the furnace in which democratic ideals are strengthened.

Ultimately, national security and individual freedom need not exist in tension. Section 152 of the BNS can and should be wielded against genuine conspiracies and violent uprisings without chilling peaceful protest, journalistic inquiry, or academic critique. Achieving that balance demands vigilant judicial interpretation, robust statutory guardrails, and a cultural commitment to open dialogue.

When the courts articulate precise standards for culpability, require pre-arrest judicial oversight, and underscore the sanctity of lawful dissent, they will reaffirm the rule of law and ensure that the nation’s unity is protected not by silencing voices but by confronting and resolving differences through democratic means.

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...