Table of Contents

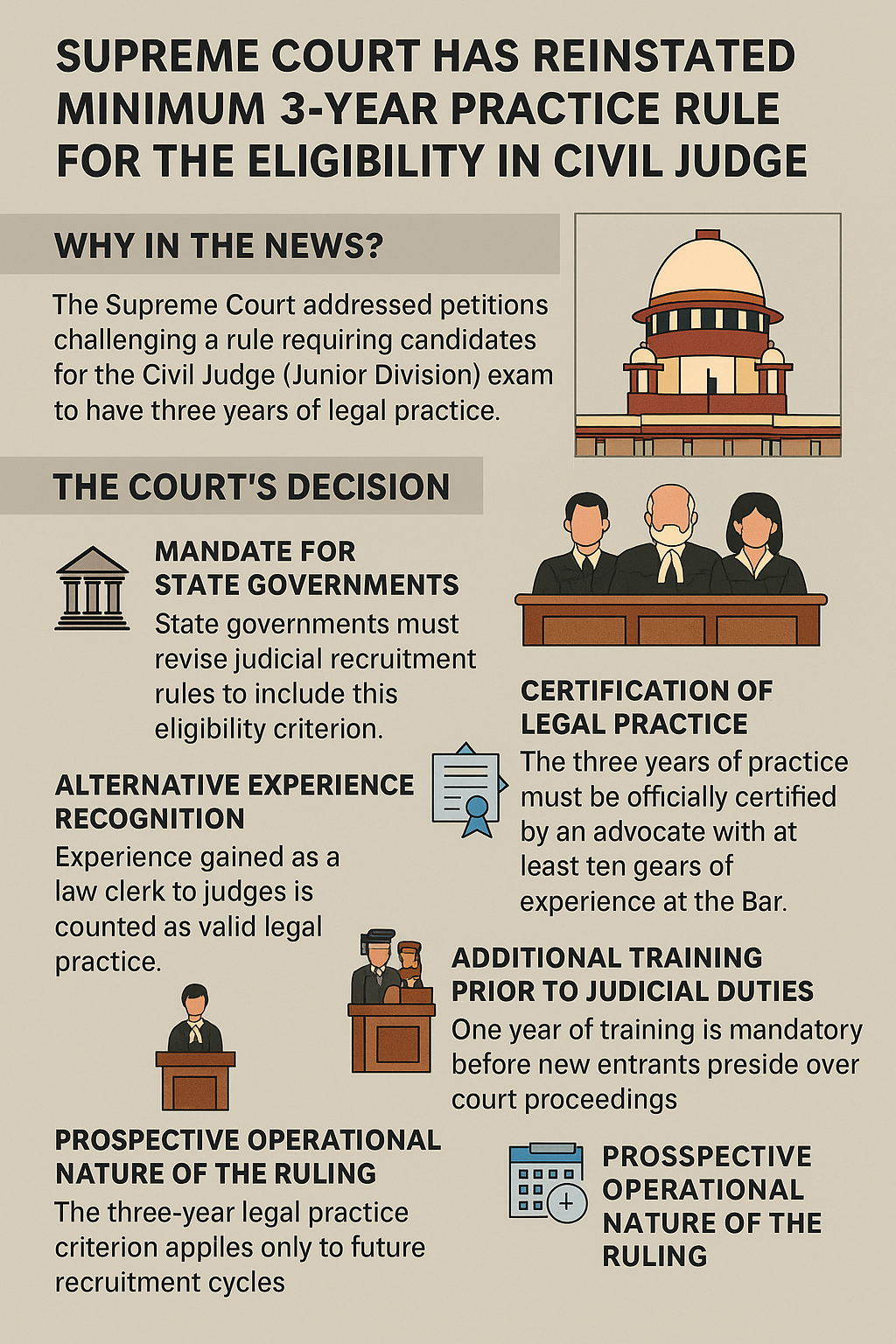

The Supreme Court addressed several petitions that challenged a rule requiring candidates for the Civil Judge (Junior Division) examination to have at least three years of legal practice. Originally, this criterion was introduced by the Madhya Pradesh High Court in 2002 through an amendment to its judicial service rules. The challenge was against making legal practice a mandatory condition for prospective civil judges.

Supreme Court has reinstated Minimum 3 Year Practice Rule for Eligibility in Civil Judge

A bench comprising three judges—BR Gavai (the Chief Justice of India at the time), AG Masih, and K Vinod Chandran decided in favor of reinstating this requirement. In essence, they restored the rule that candidates must have a minimum of three years of experience practicing law at the Bar before they can appear for the Civil Judge (Junior Division) exam.

Mandate for State Governments

The judgment further directed that all State Governments must revise their judicial recruitment rules to include this eligibility criterion. This means that moving forward, any state hiring new judicial officers for the post of a civil judge must ensure their rules reflect the need for at least three years of practice experience.

Certification of Legal Practice

To maintain the integrity of this requirement, the Court specified that the three years of practice must be officially certified. Only an advocate with a minimum of ten years of experience at the Bar is eligible to provide this endorsement. This measure intends to ensure that the candidate’s experience is both genuine and of a quality that meets the high standards expected in judicial roles.

Alternative Experience Recognition

Acknowledging that legal acumen can be developed in more than one way, the judgment also counted experience gained as a law clerk to judges as valid legal practice. This means that candidates who have worked directly with judges in a law clerk capacity can have that period considered equivalent to practicing at the Bar, thereby satisfying all or part of the three-year requirement.

Additional Training Prior to Judicial Duties

Beyond the experience criteria, the Court underscored the importance of practical training. It mandated that every new entrant into the judicial service must undergo one year of training before they are given the responsibility of presiding over court proceedings. This ensures that even after fulfilling the experience requirement, judges receive specialized training to handle the day-to-day responsibilities on the bench.

Prospective Operational Nature of the Ruling

An important clarification was made regarding the timing of this requirement. The Court ruled that the three-year legal practice criterion would apply only to future recruitment cycles. This means that if a recruitment process was already underway in a High Court when this judgment was delivered, those cases would remain unaffected by the new rule.

Underlying Rationale

A central theme of the judgment was the concern over appointing fresh law graduates as judges. The Court stressed that handling matters related to life, liberty, and property requires more than academic understanding. Practical experience, mentorship under seasoned advocates, and familiarity with courtroom procedures are crucial for effectively performing judicial duties. Hence, the requirement is a safeguard ensuring only candidates with sufficient exposure and practical knowledge are considered for the role.

Counting the Experience

For clarity, the Court specified that the three-year period should start from the date a candidate is provisionally enrolled as an advocate not from when they pass the All-India Bar Examination (AIBE). This distinction accounts for the variations in the scheduling of the AIBE across different jurisdictions, thereby standardizing how legal experience is measured.

Resumption of Recruitment Processes

Finally, the judgment allowed those recruitment processes that were previously halted (pending the resolution of these petitions) to continue. However, they must now be conducted under the amended rules that incorporate the newly endorsed criteria. This ensures a smooth transition for the judicial recruitment system without leaving any gaps in the appointment process.

Divergent Insights and Future Considerations

Understanding this ruling in a broader context reveals the judiciary’s insistence on ensuring that judges are not only theoretically knowledgeable but also practically competent. This approach underlines a broader philosophical point: the law is as much an art of practice as it is a science of principles. For someone engaged in studying or practicing law especially in contexts like judicial recruitment reflecting on the balance between academic learning and experiential wisdom can be both enlightening and practically useful.

| Key Points to Remember |

|

For those aspiring to enter the judiciary, the recent mandate requiring a minimum of three years of legal practice carries significant implications:

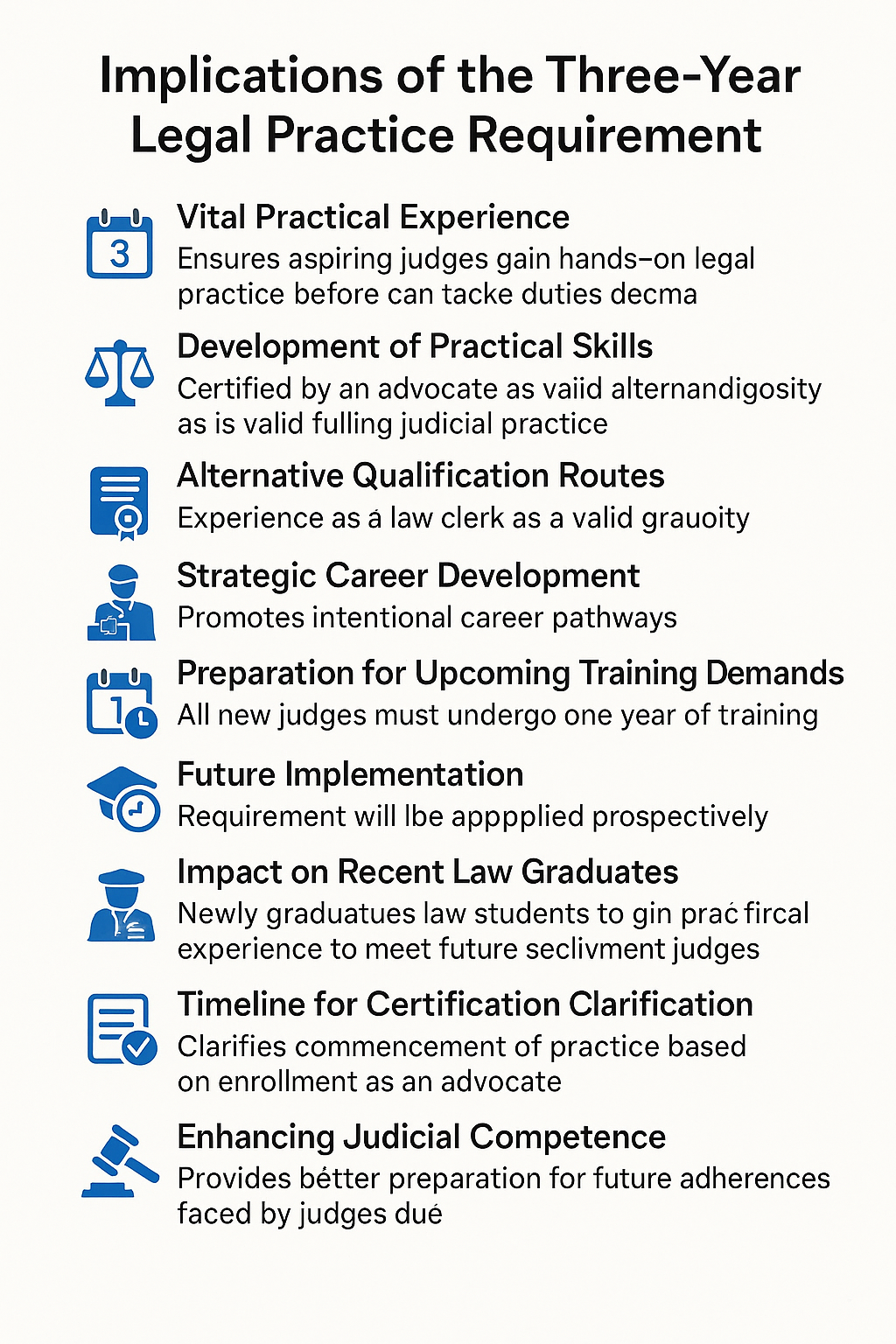

Vital Practical Experience

The ruling underscores the need for prospective civil judges to accumulate at least three years of active legal practice before they can take the Civil Judge (Junior Division) exam. This ensures that candidates are not only equipped with theoretical knowledge but also possess a hands-on understanding of legal proceedings, which is essential for effective judicial performance.

Development of Practical Skills

This requirement aims to bridge the gap between legal education and the real-world requirements of judicial duties. Aspirants who have engaged in legal practice or served as law clerks under experienced judges will develop crucial skills such as legal analysis, courtroom procedures, and sound reasoning. Such practical experience is essential for adjudicating complex cases that pertain to critical issues like life, liberty, and property.

Quality Assurance in Judicial Selections

By stipulating that the three-year practice must be certified by an advocate with a minimum of ten years at the Bar, the Court ensures the authenticity and quality of the candidate’s experience. For aspirants, this means not just fulfilling the practice requirement but also obtaining validation from a seasoned legal professional regarding their skills and contributions.

Alternative Qualification Routes

Understanding that valuable legal experience is not exclusively acquired through direct practice, the Court allows experience as a law clerk to judges as valid for meeting the practice requirement. This alternative pathway can be especially advantageous for those who obtain clerkships early in their legal careers.

Strategic Career Development

The need to complete three years of practice encourages judicial aspirants to approach their careers with greater intention. Instead of hastily transitioning from law school to a judicial role, they are urged to spend time gaining thorough, practical experience. This approach not only sharpens their legal skills but also deepens their comprehension of the judicial system.

Preparation for Upcoming Training Demands

Additionally, the Court mandates that all new judicial appointees undergo one year of training before they can preside over cases. For those aspiring to become judges, this training phase is crucial. It ensures they are adequately prepared for managing court proceedings, reinforcing the comprehensive and evolving nature of a judge’s role.

Future Implementation

It’s essential to note that this requirement will be applied prospectively. Aspirants actively engaged in recruitment processes at the time the ruling was announced are exempt from its retroactive application. Nevertheless, moving forward, any future selection cycles will comply with this new standard, making it a permanent part of the eligibility criteria.

Impact on Recent Law Graduates

The ruling highlights the judiciary’s perspective that newly graduated law students may not yet have the necessary practical experience to address judicial responsibilities effectively. For those contemplating a career in the judiciary, this indicates that simply graduating from law school is insufficient; they must proactively seek legal practice opportunities to establish a solid foundation in courtroom experience.

Timeline for Certification Clarification

The Court clarified that the three-year practice period commences from the date of provisional enrollment as an advocate, rather than from the time the All-India Bar Examination (AIBE) is cleared. This clarification assists aspirants in accurately planning their practice timeline and ensures consistency in experience calculations across various jurisdictions.

Enhancing Judicial Competence

Ultimately, the aim of this requirement is to ensure that judicial officers are thoroughly prepared to navigate the diverse and complex challenges they will encounter on the bench. Those who dedicate time to practical legal experiences are likely to cultivate a deeper understanding of legal processes, which is critical for fair and effective decision-making.

For judicial aspirants, this ruling presents both challenges and opportunities. It raises the bar by necessitating substantial practical experience prior to qualification. However, it also offers a chance to refine legal skills under the guidance of experienced mentors, ensuring that when they eventually ascend to the bench, they are well-equipped to fulfill the responsibilities of judicial office. Furthermore, this emphasis on practical experience may motivate law schools and legal institutions to enhance their programs with more experiential learning and mentorship opportunities.

For instance, one might explore how similar eligibility requirements in other disciplines (like medicine or engineering) ensure practitioners have hands-on experience before taking on roles with significant responsibilities. Additionally, examining the historical evolution of judicial appointments globally could offer insight into how judicial systems strive to balance academic credentials with practical, real-world expertise.

Moreover, one might be curious about the implications of this ruling on legal education and early career guidance. Will law schools adjust their curricula and practical training modules? How might mentorship programs evolve to bridge the gap between theoretical study and courtroom readiness? These questions open up a rich vein of further discussion around the intersection of legal education, professional certification, and the real-world application of judicial responsibilities.

Historical Background of Three year rule Practice

Supreme Court makes three years’ legal practice mandatory to apply for judicial service. A Bench headed by Chief Justice of India BR Gavai, in a judgment, concluded that infusion of fresh law graduates with zero experience in litigation was found to be detrimental.

All India Judges Association And ORS. v. Union of India and ORS| W.P.(C) No. 1022/1989

The Supreme Court is scheduled to announce its verdict on whether to reinstate the three-year minimum practice requirement for eligibility in entry-level judicial service positions, a decision emerging from the All-India Judges Association case. The bench, comprising Chief Justice of India BR Gavai, Justice AG Masih, and Justice K Vinod Chandran, is considering significant input from various stakeholders and High Courts regarding judicial recruitment standards.

Historically, most states required at least three years of legal practice to qualify for judicial roles. This requirement was abolished in 2002, permitting fresh law graduates to apply for positions like Munsiff-Magistrate without prior courtroom experience. However, there has been a growing push from numerous High Courts to reinstate this practice requirement, as advocates argue that practical exposure is vital for effective judicial performance.

The Supreme Court had previously reserved its judgment on January 28, 2025, and halted an ongoing recruitment process by the Gujarat High Court, which lacked this minimum service prerequisite. During the hearings, Senior Advocate Siddharth Bhatnagar, serving as Amicus Curiae, highlighted concerns about the risks of allowing inexperienced law graduates into the judicial system. The Court recognised these issues and acknowledged that some candidates might circumvent genuine courtroom experience by merely signing vakalaths alongside established lawyers.

While there is a strong consensus among most High Courts and State Governments in favor of reinstating the three-year requirement to maintain judicial quality, some states like Sikkim and Chhattisgarh argue against such a move, deeming it unnecessary. In its 2002 judgment, the Supreme Court, citing the Shetty Commission’s recommendations, concluded that the three-year practice requirement was hindering the recruitment of talented individuals into the judiciary and should be removed. The Court emphasized the need for rigorous training for newly appointed judicial officers for at least one to two years to compensate for their lack of practical experience.

The Supreme Court’s forthcoming judgment will have far-reaching implications for judicial recruitment and the overall quality of the judiciary across the country.

| Key Points |

| · Supreme Court Verdict on reinstating the three-year legal practice requirement for entry-level judicial posts.

· The requirement was abolished in 2002, allowing fresh graduates to apply directly. · Many High Courts support reinstatement, citing the need for practical experience. · Some states, like Sikkim and Chhattisgarh, oppose reinstatement, while most favour it. · Verdict will shape judicial recruitment and quality nationwide. |

Evolution of Judicial Service Entry Criteria in India

All India Judges’ Case (1993) and the Three-Year Rule

In All India Judges’ Assn. v. Union of India (1993) 4 SCC 288 (review), the Supreme Court standardized the entry rules for subordinate courts across the country. The Court directed that for the lowest positions in the judicial service, specifically civil judges and magistrates; a candidate must have at least three years of standing as a practicing lawyer. The Court emphasized that routine court practice not only strengthens and develops the innate qualities of intellect and character but also fosters essential virtues such as patience, temperament, and resilience necessary for judging. In summary, the Court concluded that a minimum of three years of legal practice is mandatory for recruitment into the subordinate judiciary. Prior to this judgment, individual states had various rules, but this decision established a uniform requirement for three years of Bar experience.

Rationale Behind the Three-Year Requirement

The original three-year rule was justified on the basis of the training and maturity it afforded. The Supreme Court reasoned that by practicing in court, a lawyer gains practical judgment, familiarity with legal procedures, and key virtues qualities that cannot be acquired through academic study alone. The Court stated it would be “neither prudent nor desirable” to appoint fresh graduates as judges, given the serious issues (such as liberty, property, and reputation) they would have to adjudicate. Thus, requiring lawyers to have three years of practice before elevation aimed to ensure a fundamental level of experience and competence in adjudication.

Outcomes of the Three-Year Mandate

Over the following decade, concerns arose regarding the impact of this requirement. The Shetty Commission, established in 1996, along with later commentators, noted that the pool of candidates after three years of practice at the Bar was often not the most talented. In reality, many skilled law graduates chose to pursue careers outside the bench altogether. The Court itself recognized that “with the passage of time, experience has shown that the best talent is not attracted to the judicial service,” and that “a bright young law graduate, after three years of practice, finds the Judicial Service not attractive enough.” Ultimately, the mandatory practice criterion seemed to deter high-performing advocates from attempting judicial examinations, leading to an overall decrease in candidate quality.

The Shetty Commission on Judicial Recruitment

In 1996, the Union Government appointed the First National Judicial Pay Commission (the “Shetty Commission”) to reform the conditions in the subordinate judiciary. The Commission reviewed judicial cadre structures, promotions, and recruitment processes. Among its recommendations, it advocated for rationalizing judicial cadres by unifying structures and jurisdictions, along with ensuring career promotions for lower-court judges. Notably, the Commission proposed that only up to 25% of District Judge posts be filled through direct recruitment from the Bar, with the remainder filled through promotions. Importantly, it identified the three-year Bar experience requirement as a barrier to entry, pointing out that it discouraged candidates and contributed to a lower-quality applicant pool.

Supreme Court 2002 – Abolishing the Three-Year Rule

In 2002, the Supreme Court revisited the issue and acted on the key recommendations of the Shetty Commission. In All India Judges Assn. (3) v. Union of India (2002) 4 SCC 247, the Court abolished the three-year practice requirement for new entrants. It explicitly accepted the Commission’s finding that the rule was counterproductive, noting that it was preventing the “best talent” from joining the bench, as law graduates often found the Judicial Service unattractive after three years of practice. Consequently, the Court ruled that it would no longer be mandatory for applicants wishing to enter the Judicial Service to have three years of standing as advocates. This change meant that even recent law graduates without any Bar experience could now sit for subordinate judicial exams.

The Court directed all High Courts and state governments to amend their judicial service rules accordingly, removing the experience clause so that fresh law graduates could be eligible for recruitment to the lower judiciary. To address concerns regarding inexperience, the Court recommended that new entrants undergo structured training, proposing a training period of not less than one year, preferably two years. As a result, the three-year practice requirement was replaced by a structured training period for new judges.

Implications for Quality and Career Attractiveness

Abolishing the mandatory practice period aimed to improve both the quality of candidates and the attractiveness of judicial careers. By opening up entry exams to high-performing graduates, the Court sought to enhance the overall standards within the judicial system.

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...