Table of Contents

Context: In the case of Tejender Pal Singh v. State of Rajasthan (2024), the Rajasthan High Court cautioned against the potential misuse of Section 152 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS).

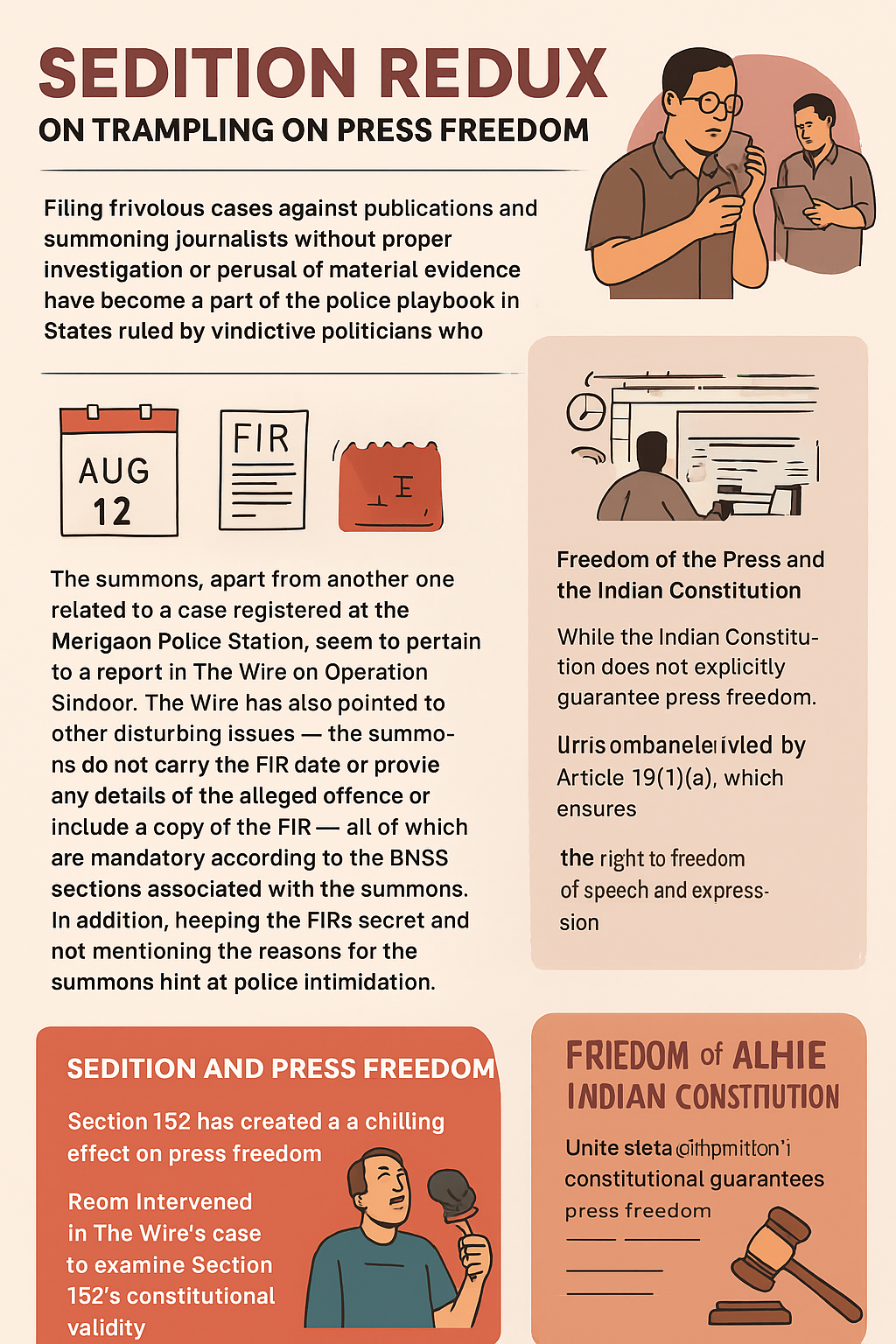

The freedom of the press is fundamental to a democratic society, both as a safeguard against arbitrary authority and a means for citizens to stay informed about governmental actions. In India, the application of sedition laws against journalists and media organisations persists, raising significant worries about the deterioration of constitutional rights.

The recent summoning of top journalists Siddharth Varadarajan and Karan Thapar of The Wire by the Assam Police under Section 152 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) highlights the weaponisation of the new sedition law to stifle dissent. The concerning elements of these summons – absence of FIR particulars, lack of transparency, and evident police harassment indicate a problematic continuation of colonial practices despite India’s democratic commitments.

More in News

- This criminalises acts that endanger the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India.

- In 2022, the Supreme Court suspended pending trials and proceedings under Section 124A (sedition) of the IPC, anticipating its reconsideration by the government.

- The Union Home Minister verbally announced the repeal of sedition as an offence.

- Section 152 of the BNS criminalises acts that excite secession, rebellion, or subversion, as well as those that encourage separatism or endanger sovereignty, unity, and integrity.

- While the term ‘sedition’ has been omitted in the BNS, Section 152 retains similar elements, raising concerns about its potential misuse.

Historical Context of Sedition in India

- Sedition, as a legal offence, was initially established in Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, implemented by the colonial administration to stifle nationalist sentiments, particularly targeting figures such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi.

- The legislation prohibited any actions or expressions that incited “hatred or contempt” or “provoked disaffection“ towards the government.

- Originally designed to fortify the colonial state, its continued existence in independent India has sparked controversy.

- In 2022, the Supreme Court mandated that all sedition proceedings be suspended, acknowledging the detrimental impact of the rule on free expression.

- Instead of eliminating sedition, the legislators reinstated it in the BNS as Section 152, employing larger and more ambiguous terminology.

Section 152 of the BNS: A Reconfigured Sedition Law

- Section 152 of the BNS penalises actions that jeopardise the “sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India.”

- In contrast to its predecessor, it establishes a significantly lower standard for prosecution, utilising ambiguous phrases such as “knowingly,” which permit prosecution even in the absence of malicious intent.

- The Assam Police’s summons in The Wire case seems connected to reports regarding Operation Sindoor; nonetheless, the lack of procedural adherence, specifically, the absence of an FIR document and details of the alleged offence, elicits significant constitutional apprehensions.

- The coincidence of these summons with the Supreme Court’s notification about The Wire’s petition contesting the constitutional legality of Section 152 further exemplifies the state’s contempt of judicial scrutiny.

What Constitutes Sedition under BNS?

- The offence of sedition is delineated in Section 152 of BNS.

- This section originates from Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC).

- The offence of Sedition was initially established in 1870 by the British Government to penalise actions of hatred, contempt, or disaffection towards Her Majesty or the Crown.

- The offence of sedition under section 124-A of the IPC has been abolished in the BNS; nevertheless, a new provision, identically phrased, has been introduced in section 152 by the legislators in Parliament.

- It penalises actions or efforts that provoke secession, armed insurrection, or subversive conduct, or promote separatist sentiments that jeopardise the nation’s stability.

- At first glance, it seems that this provision has reinstated Section 124A of the IPC; yet, it remains ambiguous which of the two sections is more rigorous.

- The penalty under Section 124A may consist of life imprisonment or a term of up to three years, with the possibility of an additional fine.

- Under BNS, the prescribed punishment is either life imprisonment or a term of seven years, accompanied by a mandatory fine.

- The provision seeks to uphold national integrity and avert disintegration.

- The legislature has implemented these rules to mitigate actions that might divide the nation, considering India’s historical context and the multiplicity of secessionist movements.

Problems with Section 152 of BNS

Vague Terminology

Section 152 criminalises acts that “endanger the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India” without defining what constitutes such endangerment.

- This vagueness allows for broad interpretations by enforcement authorities.

- Criticism of political or historical figures could be construed as endangering national unity, leading to potential legal actions against individuals expressing dissent.

Lowered Threshold for Liability

- The inclusion of the term “knowingly” lowers the threshold for committing an offence under Section 152, especially in the context of social media.

- A person could be prosecuted for sharing a post that reaches a larger audience and may provoke prohibited activities, even without malicious intent.

Potential for Abuse

The lack of a requirement to establish a causal link between speech and its consequences raises concerns about abuse similar to that seen under Section 124A of the IPC.

- Historical data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) indicated that out of 548 arrests for sedition between 2015 and 2020, only 12 resulted in convictions.

- This suggests a high potential for misuse in broader and less specific provisions like Section 152.

Recommendations by the Court

Judicial Interpretation

The judiciary should adopt a consequentialist interpretation when applying Section 152 to balance national interests with freedom of expression.

- Courts have historically focused on actual consequences rather than merely the content of speech.

- Precedents from cases like Balwant Singh v. State of Punjab (1995) and Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar (1962) emphasise the need for a direct causal relationship between speech and its impact.

Guidelines for Enforcement

- The Supreme Court should develop clear guidelines delineating the boundaries for terms used in Section 152 to prevent arbitrary enforcement.

- This approach mirrors its previous rulings, such as in K. Basu v. State of West Bengal regarding arrests.

Encouraging Free Expression

There should be a liberal space for diverse thoughts and expressions, especially in the age of social media.

- The concept of a “marketplace of ideas,” articulated by Justice Holmes in Abrams v. United States, should guide enforcement to foster democratic dialogue.

- Safeguards Against Abuse: Given the lack of built-in safeguards within Section 152, it is crucial to ensure that enforcement does not become a proxy for stifling dissent or criticism under a guise similar to sedition laws.

What distinguishes Section 124A of the IPC from Section 152 of the BNS?

Section 124A of the IPC pertains to sedition, stipulating that any individual who, through spoken or written words, signs, visible representations, or other means, incites or attempts to incite hatred, contempt, or disaffection towards the legally established Government of India, shall be subject to punishment, which may include life imprisonment, with the possibility of a fine, or imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years, also with the possibility of a fine, or solely a fine.

- Explanation 1. The term “disaffection” encompasses disloyalty and any sentiments of hostility.

- Explanation 2. Remarks that convey disapproval of governmental acts aimed toward their modification by legal methods, without inciting or seeking to incite hatred, contempt, or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this provision.

- Explanation 3. Remarks that convey disapproval of governmental administrative actions, without inciting or seeking to incite hostility, contempt, or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this section.

Section 152 BNS

- Actions jeopardizing the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India– Any individual who intentionally or knowingly, through spoken or written words, signs, visual representations, electronic communication, financial means, or other methods, incites or attempts to incite secession, armed rebellion, or subversive activities, or fosters separatist sentiments, or jeopardizes the sovereignty, unity, or integrity of India, or engages in such acts shall be subject to life imprisonment or imprisonment for a term not exceeding seven years, and may also incur a financial penalty.

- Comments that express disapproval of governmental measures or actions, aimed at obtaining their modification through lawful means without inciting or attempting to incite the activities mentioned in this section, do not constitute an offence under this section.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Section 152 and Sedition Law

Advantages

- National Security Safeguards: Advocates contend that sedition laws preserve the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of the state, particularly in the face of secessionist movements, terrorism, and adversarial propaganda.

- Deterrence Against Hostile Acts: Section 152 establishes legal measures to prohibit speeches or publications that may undermine public order.

- State Authority: These statutes enable governments to respond promptly to the encouragement of violence or disaffection, thereby guaranteeing stability.

Disadvantages

- Ambiguous and Overbroad Language: The imprecise terminology of Section 152, such as “knowingly” and “endangering unity,” facilitates potential misuse against mild dissent.

- Repression of Dissent: Journalists, activists, and opposition members are disproportionately targeted, eroding the democratic arena for discourse.

- Colonial Continuity: Although “rebranded,” the legislation preserves the essence of colonial sedition laws, which are at odds with constitutional liberties.

- Chilling Effect: The prospect of prosecution deters authentic journalistic reporting and public dissent on governmental acts.

- Absence of Procedural Safeguards: The Wire’s case demonstrates that the non-disclosure of FIR details and ambiguous summons exemplify procedural infractions.

The Freedom of the Press and the Indian Constitution

- The Indian Constitution does not directly guarantee “freedom of the press,“ but it is inferred from Article 19(1)(a), which guarantees the right to freedom of speech and expression.

- The Supreme Court has always upheld that press freedom is essential to this fundamental right.

- Romesh Thapar v. State of Madras (1950): The Court invalidated pre-censorship instructions, acknowledging the essential role of press freedom in a democracy.

- Indian Express Newspapers v. Union of India (1985): Confirmed the essential role of the press in the functioning of democracy.

- Article 19(2) allows for “reasonable restrictions“ on expression to safeguard sovereignty, integrity, and public order.

- Subsequent administrations have employed this provision to rationalise limitations; however, the judiciary has cautioned against its misuse.

- The application of Section 152 BNS against journalists, absent definitive proof of incitement, prompts inquiries over the continued “reasonableness” of such prohibitions.

Sedition and Press Freedom in the Global Context

- Sedition laws have faced extensive criticism worldwide for their incompatibility with democratic principles.

- Numerous democracies, such as the United Kingdom, have repealed sedition laws, acknowledging their detrimental impact on free expression.

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Article 19 ensures freedom of expression, limited solely by limits essential for safeguarding national security, public order, or the rights of others. India is a signatory to the ICCPR; yet, the ambiguity of Section 152 potentially contravenes these international obligations.

- The UN Human Rights Commission has persistently advocated for the removal or amendment of sedition laws to conform to international human rights standards.

- The persistent application of sedition laws in India compromises national democratic principles and diminishes its credibility as the “world’s largest democracy“ within the international community.

Judicial Supervision and the Path Ahead

- The Supreme Court’s notification on The Wire’s petition, together with interim safeguards against coercive measures, signifies judicial acknowledgement of the perils associated with Section 152.

- Nonetheless, the Assam Police’s neglect of this safeguard signifies more profound institutional issues.

- Unless the judiciary issues clear guidelines, strikes down overbroad provisions, and holds law enforcement accountable, sedition laws will continue to be weaponised.

- Enhancing press freedom necessitates:

- Legislative Reforms: Repeal or restrict Section 152 to comply with constitutional and international standards.

- Institutional Accountability: Law enforcement and governmental agencies must incur sanctions for the misuse of sedition laws.

- Civil Society Oversight: Media entities and advocacy organisations must persist in contesting unlawful laws.

Final Assessment

- The application of Section 152 BNS against journalists of The Wire exemplifies the systematic use of sedition laws, whether outdated or renamed, to coerce dissent.

- Although national security is a valid issue, ambiguous and excessively broad sedition laws contribute more to stifling governmental critique than to safeguarding sovereignty.

- The Indian Constitution envisions a strong press as a fundamental democratic institution, and international standards need the same.

- Unless India addresses the colonial heritage of sedition forcefully, its democratic potential will remain unfulfilled, and press freedom will persistently be jeopardised.

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Social Media, Judicial Narratives, and t...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Can the Marital Rape Exception Immunize ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right ...