Table of Contents

Why in the news?

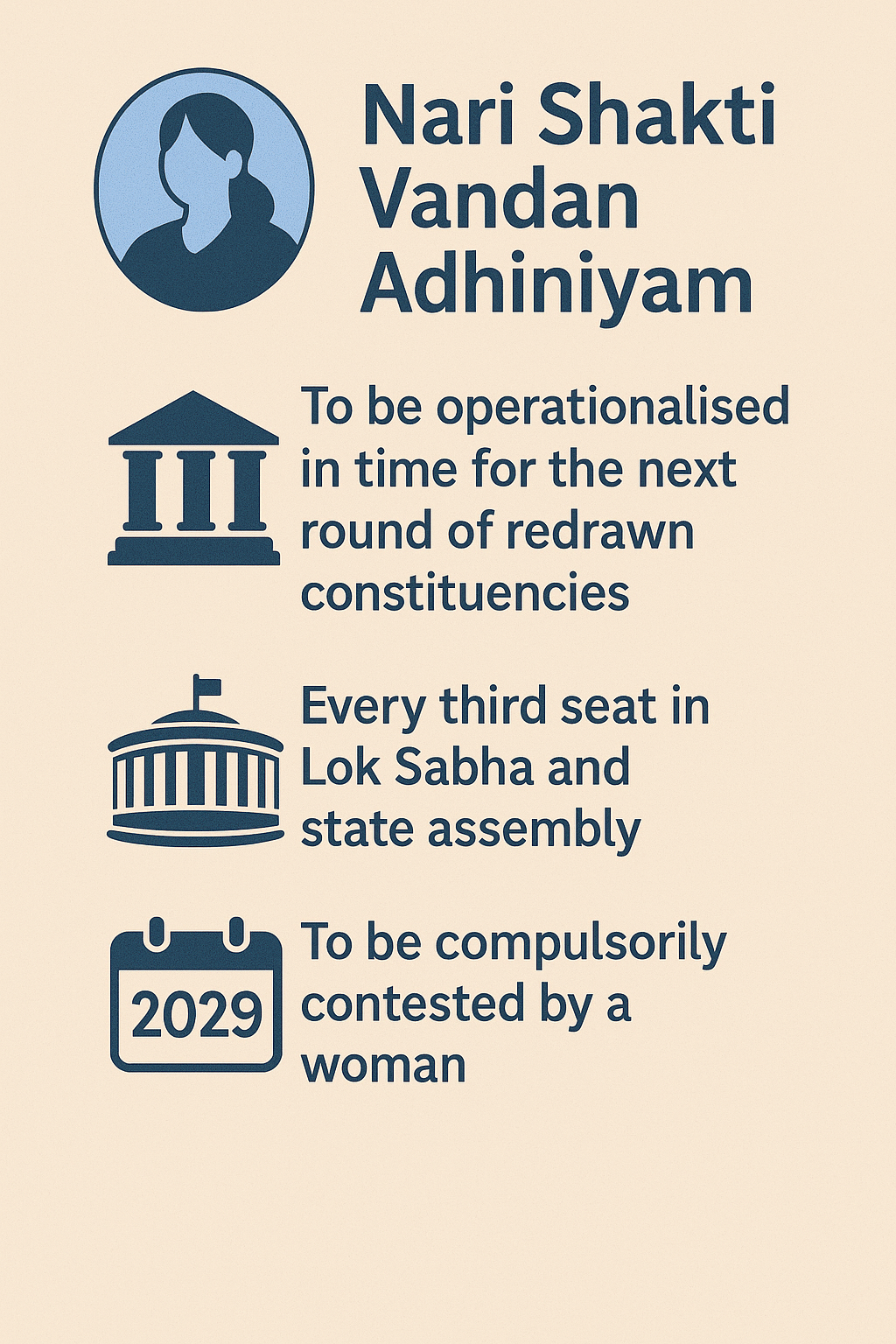

The Union government has signalled that the long-pending women’s reservation law is finally moving from statute book to street-level politics. Officials say the Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam the Constitution (128th Amendment) Act, 2023 will be operationalised in time for the next round of redrawn constituencies, so that every third seat in the Lok Sabha and in each state, assembly is compulsorily contested by a woman in the 2029 general election.

Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam

It inserts new Articles 330A and 332A in the Constitution, mandating 33 per cent reservation for women in the Lok Sabha, the Delhi Assembly and every state legislature. It extends the quota within the already-reserved SC/ST seats, guaranteeing intersectional representation and provides that the reservation will rotate from one constituency to another after every delimitation, so the burden (and benefit) is evenly shared.

Parliament deliberately linked implementation to two preparatory steps:

- The “first Census after the Act comes into force” (the Centre has now scheduled an all-India digital census whose two phases end by March 2027).

- A fresh delimitation of constituencies based on the new population data. Only when the Delimitation Commission completes this redrawing exercise can the Election Commission notify which seats will be women-only contests.

- Census enumeration ends in March 2027. Data processing & publication late 2027/early 2028 (government insists digital methods will accelerate release). Delimitation Commission: 12-18 months for hearings, draft maps, objections and final order.

If those milestones hold, the revised electoral map can be frozen before the Model Code of Conduct kicks in for the 2029 Lok Sabha polls, making the one-third quota a lived reality for the first time. Political ripples. Delimitation always reshuffles the deck, northern states that have grown faster demographically since 1971 stand to gain seats; southern states fear dilution of their current weight. Union ministers have publicly promised “no state will lose out”, hinting at creative seat-expansion formulas to allay those anxieties. Expect intense bargaining once draft constituency maps appear.

Why Reservation was needed?

India’s Lok Sabha has only 78 women MPs (about 14%) today, below the global average and far behind Rwanda, Mexico or Nepal, which already use quotas. Advocates argue that a critical mass of women lawmakers changes spending priorities (towards health, water, education) and reshapes policy debates on care work, safety and labour-force participation. Critics worry party gate-keepers may continue fielding relatives (“token wives and daughters”), so parallel reforms transparent candidate-selection, campaign finance support and intra-party mentoring remain essential.

Provisions in the Act

The Act says 15 years, but every previous sunset clause for reservations has been routinely extended. Women already hold 46% of seats in panchayats because of a similar quota.

Background of the Act

The Constitution (106ᵗʰ Amendment) Act, popularly known as the Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam, was passed by Parliament in September 2023, after years of delays. This landmark legislation introduces new Articles 330-A and 332-A, mandating that every future Lok Sabha and all state legislatures, including Delhi’s assembly, allocate one-third of their total seats for women. Notably, this quota will also be applied within the existing Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) constituencies, ensuring broader representation.

What sets this amendment apart from most others is its unique built-in mechanism for implementation. The quota will come into effect only after certain preparatory steps are fulfilled. The first step is the first nationwide Census conducted after the law’s commencement, which the government has scheduled for 1 March 2027. This Census will utilize mobile applications and a central digital portal for data collection. The second step involves a fresh delimitation of constituencies based on the newly gathered population data, a process that will be overseen by a Delimitation Commission established by a separate act of Parliament. This sequencing makes the Census a crucial element for this reform, as its district-level population tables, along with the caste breakdown, will inform the Delimitation Commission on how many seats each state should be allocated and the new constituency boundaries. Once this data is formalized, the Election Commission will designate every third constituency as “women-only” for the 2029 general elections and subsequent state assembly polls.

The thoughtful sequencing of these conditions serves several important purposes. Firstly, by attaching the quota to the Census, Parliament shields the law from potential legal challenges that could arise from modifying boundaries mid-cycle for political gain. Furthermore, aligning delimitation with the Census upholds the principle of “one person, one vote,” ensuring that each constituency reflects roughly equal population sizes. The current constituency map, based on the 1971 Census, has resulted in significant disparities, with many northern districts containing far more voters than the national average, while several southern districts reflect a lower population. Additionally, the timeline to 2029 provides political parties the necessary time to cultivate a pipeline of female candidates, promoting long-term planning rather than a last-minute scramble to fulfill the quota.

There are several intricacies within the amendment that warrant attention. The reservation period for women lasts “15 years from commencement,” but Parliament has the option to extend this by simple amendment, similar to how SC and ST quotas have been continued since 1950. Furthermore, the rotation of reserved seats after each delimitation ensures that no constituency is permanently allocated to women, thus allowing opportunities for men as well as preventing any one family’s dominance in representation. Importantly, the quota will apply within SC/ST allocations, which means approximately 11 SC and two ST constituencies in the Lok Sabha will also be set aside for women, promoting intersectional representation that harmonizes caste equality with gender equity.

As we approach 2029, several key developments will be worth monitoring. Limiting the potential for disputes, southern states, particularly concerned about their diminishing political influence due to slower population growth, have been reassured by senior ministers that “no state will lose out” during the reapportionment process, signaling a possible overall expansion of the Lok Sabha to alleviate these concerns. However, if Parliament does not promptly pass a Delimitation Act after the Census data is published, it risks delaying the implementation of the quota beyond the targeted date. Additionally, without measures such as transparent primaries or financial support to facilitate women’s candidacy, there are concerns that the new quota could inadvertently reinforce dynastic politics by leading parties to nominate female relatives of incumbent male legislators.

Relevant Constitutional Yardsticks

Article 81(2)(a) says each state’s Lok Sabha quota should, as far as practicable, keep the ratio between its population and number of seats the same across the country, with an express carve-out for very small states (population under six million). This is the textual anchor for the one-person-one-vote principle. Article 82 operationalises that principle by directing a post-Census readjustment and empowering Parliament to decide the mechanics through ordinary legislation.

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...