Table of Contents

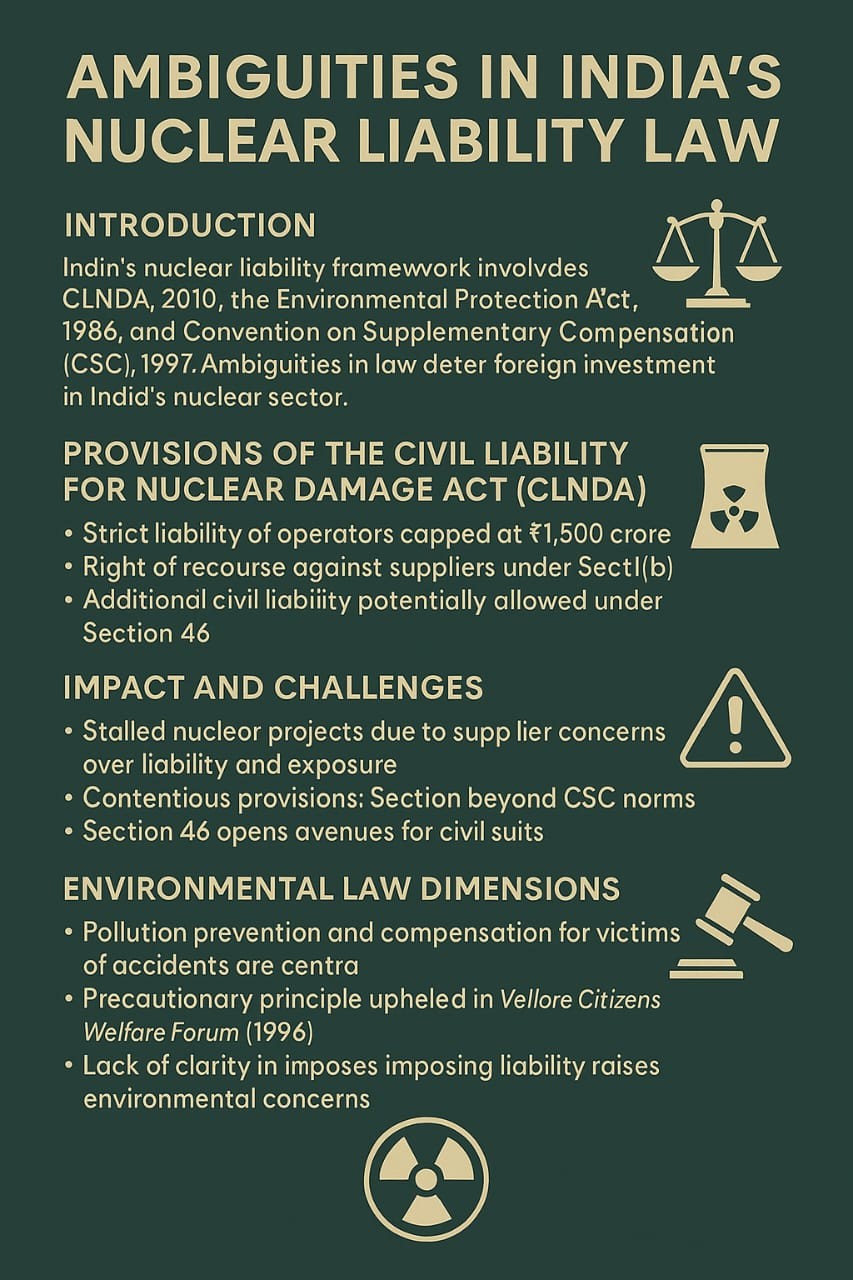

India’s advancement in augmenting its civil nuclear energy capability has been consistently hindered by legal intricacies related to nuclear liability. Although designed to protect victims’ rights and enhance accountability, the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act (CLNDA), 2010, has generated considerable difficulties, particularly concerning supplier liability. The legal ambiguities have dissuaded foreign investment, impeded critical nuclear initiatives, and heightened apprehensions regarding India’s conformity with international legal standards.

The Legal Framework of Civil Nuclear Liability in India

- The nuclear liability framework in India is mostly regulated by:

- The Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act (CLNDA) 2010

- The Atomic Energy Act of 1962

- India’s ratification of the Convention on Supplementary Compensation (CSC), 1997

- The CLNDA was enacted by Parliament in 2010.

- It constitutes the legal framework that shapes India’s reaction to nuclear events.

- It is founded on the global principles of civil nuclear liability established in the Vienna Convention, Paris Convention, and Brussels Supplementary Convention.

- It established a framework for compensating victims for damages resulting from a nuclear incident, delineating liability and outlining compensation procedures.

Characteristics of the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damages Act

- The CLNDA was established to ensure timely compensation for victims of nuclear catastrophes and to harmonise Indian legislation with international commitments under the CSC.

- It established the principle of “strict and no-fault liability” for nuclear operators, assigning the main responsibility for nuclear damage to them, regardless of culpability.

- This Act delineates the operator’s obligation for nuclear disasters up to 1,500 crore, necessitating insurance or financial security.

- If the damage claims above ₹1,500 crore, the CLNDA anticipates government intervention.

- The Act has constrained the government’s liability to the currency equivalent of 300 million Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), approximately ₹2,100 to ₹2,300 crore.

- The act not only establishes a timetable for compensation claims but also empowers the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board to report events within 15 days.

- The statute also establishes a Nuclear Damage Claims Commission to provide fair compensation and resolve disputes.

Ambiguities in Supplier Liability Provisions

Clause 17(b): Liability of Supplier

- Section 17(b) is one of the most disputed clauses, stipulating that the operator (NPCIL) will possess a right of recourse or appeal in the event of loss arising from: “An action by a supplier or their employee involving the supply of equipment or materials with either patent or latent defects, or substandard services.”

- This provision surpasses the two conditions authorised by the CSC:

- Unless explicitly stipulated in a contract (Section 17(a)), or

- Intent to cause damage (Section 17(c)).

- Section 17(b) imposes a level of accountability for inadvertent provision of defective equipment that is atypical in international practice, thereby discouraging foreign suppliers from engaging in India’s civil nuclear program.

Section 46: Supplementary Civil and Criminal Accountability

- Section 46 articulates: This Act shall not infringe upon any individual’s right to seek compensation under any other legislation.

- This paves the way for tort-based civil litigation or criminal actions beyond the CLNDA.

- This uncontrolled, indeterminate liability, particularly in the absence of governmental clarification regarding “nuclear damage”, subjects both operators and suppliers to boundless legal and financial dangers.

- Sections 17(b) and 46 together establish a dual exposure issue, whereby suppliers encounter liabilities unanticipated by the CSC or their respective national legislation.

Impact on Civil Nuclear Agreements and Projects

- Numerous significant nuclear collaborations have stalled owing to liability apprehensions:

- The Jaitapur Nuclear Power Project’s agreement with Électricité de France (EDF) has been stagnant since 2009, notwithstanding amended Memoranda of Understanding in 2016 and 2018.

- The Kovvada Nuclear Project’s proposed collaboration with U.S.-based vendors is now in a state of uncertainty.

- The Kudankulam Reactors in Russia represent the sole significant overseas partnership that advanced before the enactment of the CLNDA.

- India’s ambitious nuclear strategy, aimed at achieving substantial energy security, hinges on the resolution of liability conflicts that persistently trouble private suppliers, particularly from the United States, France, and Japan.

Constitutional and Environmental Law Dimensions

Right to Life as guaranteed in Article 21

- The Supreme Court has determined that the right to a clean and safe environment is inherent in Article 21 of the Constitution.

- Following a nuclear disaster, the entitlements to compensation, rehabilitation, and environmental remediation are encompassed within the protective scope of this article.

Principles of Precaution and Polluter Pays

- As articulated in decisions such as Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India (1996), India has integrated international environmental principles into its local legal framework.

- The CLNDA adheres to the polluter-pays concept by holding operators accountable; nonetheless, the vague extension of obligation to suppliers, lacking explicit statutory protections, jeopardises due process and corporate sustainability.

Relevance in the International Arena

- India’s nuclear liability law must reconcile domestic constitutional requirements with international nuclear liability norms.

- The CSC, to which India joined in 2016, is designed to:

- Assign liability exclusively to operators.

- Advocate for consistency in liability frameworks.

- Guarantee victims’ access to timely and sufficient compensation.

- India’s deviation from the essence of the CSC in Sections 17(b) and 46:

- Has dissuaded suppliers from CSC member nations.

- Subverts India’s reputation as a dependable civil nuclear collaborator.

- Undermines possibilities for future bilateral and multinational nuclear collaboration.

- Countries such as the United States and France have pursued legislative clarifications and insurance frameworks.

- The uncertainty in enforcement and insurance liability thresholds persists in obstructing advancement.

Policy Debate and the Way Forward

- The government contends that Section 17(b) is permissive rather than mandatory.

- Nonetheless, the statutory language contradicts this perspective, indicating that courts may construe the law as allowing claims even in the absence of contractual provisions.

- Legal experts advise:

- Modifying Section 17(b) to limit recourse exclusively to CSC stipulations.

- Clarifying Section 46 via official notices that restrict civil lawsuits.

- Clarifying the definition of “nuclear damage” as per Section 3(e) of the Act.

- Establishing a specialised civil tribunal for nuclear claims to avert the proliferation of cases.

- Establishing a government-supported supplier insurance consortium to distribute risks.

- India’s civil nuclear liability framework exemplifies a complex equilibrium between safeguarding public welfare, maintaining environmental protection, and fostering foreign investment.

- Nonetheless, uncertainties regarding supplier liability under the CLNDA, especially Sections 17(b) and 46, have emerged as impediments to nuclear development.

- For India to become a significant civil nuclear power, it must align its legislation with international standards, offer legal certainty to suppliers, and cultivate a secure, sustainable, and attractive nuclear environment for investment.

Warring Couples Cannot Make Courts Their...

Warring Couples Cannot Make Courts Their...

Tackling Child Trafficking in India: Leg...

Tackling Child Trafficking in India: Leg...

In Overcrowded Prisons, Justice Has Lost...

In Overcrowded Prisons, Justice Has Lost...