Table of Contents

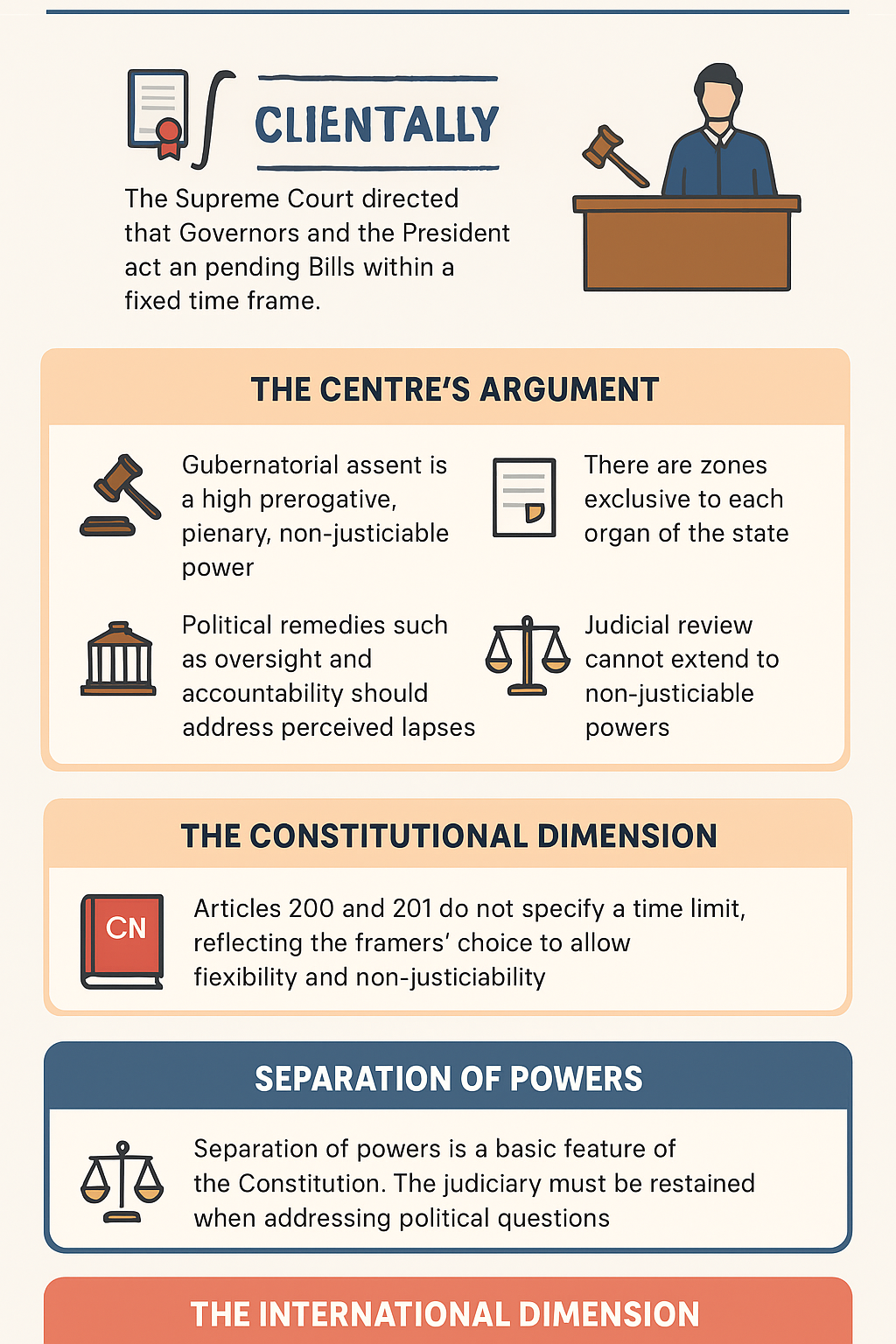

The interplay among the Legislature, Executive, and Judiciary in India has consistently been a topic of constitutional debate, particularly when one branch of the State is viewed as exceeding its limits. The Union Government, represented by Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, vehemently contested the Supreme Court’s ruling that mandates a three-month timeframe for the President and Governors to respond to Bills submitted by State Legislatures. This development raises substantial constitutional issues regarding the separation of powers, the non-justiciable nature of certain executive activities, and the potential dangers of judicial overreach.

Background of the Dispute

- In April 2024, a two-judge bench of the Supreme Court established a definitive timeline for Governors to address pending State Bills and instructed that the President must render a decision within three months on Bills held for her review by Governors.

- This was unique, given that the Constitution does not explicitly provide any time-bound framework under Articles 200 and 201, which regulate gubernatorial assent to Bills.

- President Droupadi Murmu subsequently sent 14 critical questions to a larger Bench of the Supreme Court concerning the constitutional legality of these timetables.

- The five-judge Bench is currently evaluating the constitutional validity of judicially mandated time constraints for gubernatorial or presidential actions.

Centre’s Written Submissions before the Supreme Court

- The Centre, represented by Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, said that the Supreme Court’s endeavour to establish a timeline:

- Contravenes the principle of separation of powers by encroaching upon a domain solely designated for the Executive and Legislature.

- Disrupts the constitutional balance among state organs, so modifying the intricate balance intended by the Constitution’s architects.

- Misrepresents the authority of assent, which the Centre defines as a “high prerogative, plenary, non-justiciable power” of a unique nature.

- Endangers judicial supremacy, which contradicts the basic structure doctrine of the Constitution.

- Establishes an institutional hierarchy that effectively subordinates the Executive to the Judiciary within the context of legislative-executive interaction.

- Disregards the absence of time constraints in Article 200 and Article 201, which indicates the architects’ purpose to maintain flexibility in the governor’s discretion.

- Mehta asserted that “if any organ is allowed to usurp the functions of another, the result would be a constitutional disorder not anticipated by its creators.”

Gubernatorial Assent: Nature and Constitutional Status

- Articles 200 and 201 of the Constitution delineate the parameters for gubernatorial assent. According to Article 200, when a Bill approved by the State Legislature is sent to the Governor, the Governor may:

-

- Give assent.

- Refrain from giving assent,

- Return the Bill for reconsideration, or

- Reserve it for the President’s consideration.

- Article 201 grants the President the authority to either approve the Bill or refuse approval. Both provisions lack explicit time constraints.

- The Centre contended that this silence was intentional, indicating the framers’ recognition that certain judgments entail intricate political considerations and, hence, cannot be subject to judicial standardisation.

- The Centre emphasised that Governors and the President are not “aliens” to the federating units. Instead, they epitomise the national democratic will and signify the constitutional fraternity between the Union and the States.

- Treating them solely as ambassadors of the Centre diminishes their wider constitutional function.

Judicial Review and Its Constitutional Limits

The Centre’s response highlighted that although judicial review is fundamental to the Indian Constitution, there exist areas of non-justiciability where judicial intervention is prohibited. The argument posits that gubernatorial assent resides within this domain because:

- It involves political, rather than solely legal, factors.

- No judicially workable criteria exist for assessing whether consent has been excessively postponed.

- Extending judicial review into this area jeopardises the equilibrium of powers and compromises constitutional federalism.

Judicial Overreach and Article 142

The Solicitor General strongly criticised the reliance on Article 142, which empowers the Supreme Court to issue orders essential for “complete justice.“ He contended that:

- Article 142 does not confer upon the judiciary the ability to supersede constitutional provisions.

- The Court is nonetheless obligated to adhere to the Constitution, even in accordance with Article 142.

- Establishing notions like “deemed assent” through judicial fiat would pervert the constitutional and legislative processes.

Separation of Powers in the Indian Constitution

- The notion of separation of powers, although not officially articulated in the Constitution, is inherent in its framework. Articles 50, 121–122, and 212 demonstrate the framers’ intention to maintain a separation of legislative, executive, and judicial powers, while allowing for overlapping checks and balances.

- The Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) case affirmed that the separation of powers constitutes an integral component of the Constitution’s basic structure. The Centre invoked this doctrine to warn against judicial overreach, which threatens to disrupt the equilibrium in favour of judicial supremacy.

Separation of Powers: International Perspectives

United States of America

- The American model is based on a rigid separation of powers, with the judiciary wielding the authority of judicial review (created in Marbury v. Madison). Nonetheless, in the United States, specific functions, such as the President’s veto authority, are regarded as political concerns and are predominantly exempt from judicial examination.

United Kingdom

- In the Westminster system, the separation of powers is less stringent; yet, traditions and judicial constraint inhibit excessive intrusion. The monarch’s approval of Bills, while ceremonial, is not bound by court timetables, demonstrating deference to non-justiciable powers.

France and Germany

- Both nations acknowledge a separation of powers; however, constitutional courts possess ultimate authority over legal matters. Political inquiries, meanwhile, lie beyond the jurisdiction of the judiciary.

- These global trends bolster the Centre’s assertion that gubernatorial assent constitutes a political-constitutional function, inappropriate for judicial oversight.

Implications for Indian Federalism

- The discourse has substantial ramifications for Centre-State relations and Indian federalism.

- Judicially imposed timetables may limit the President and Governors, diminishing their constitutional authority.

- It may also alter the power dynamics in favour of State Legislatures relative to the Union.

- Conversely, the lack of timeframes jeopardises the timely passage of Bills, so undercutting the intentions of elected State Legislatures.

- The issue, consequently, resides in harmonising State legislative independence with the Union’s function in maintaining constitutional equilibrium.

Conclusion

- The ongoing debate underscores the fragile equilibrium among India’s constitutional entities. Although judicial review is crucial for curbing administrative caprice, the Supreme Court’s endeavour to establish strict timetables for gubernatorial and presidential approval poses a risk of judicial overreach and undermines the idea of separation of powers.

- The Solicitor General cautioned that assigning the powers of one branch to another would result in a “constitutional disorder not anticipated by the framers.”

- The final decision will necessitate the Supreme Court to meticulously adjust its authority under Article 142, reassert adherence to constitutional ambiguities, and guarantee that the judiciary does not override the democratic mechanisms intended to rectify institutional deficiencies.

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...