Table of Contents

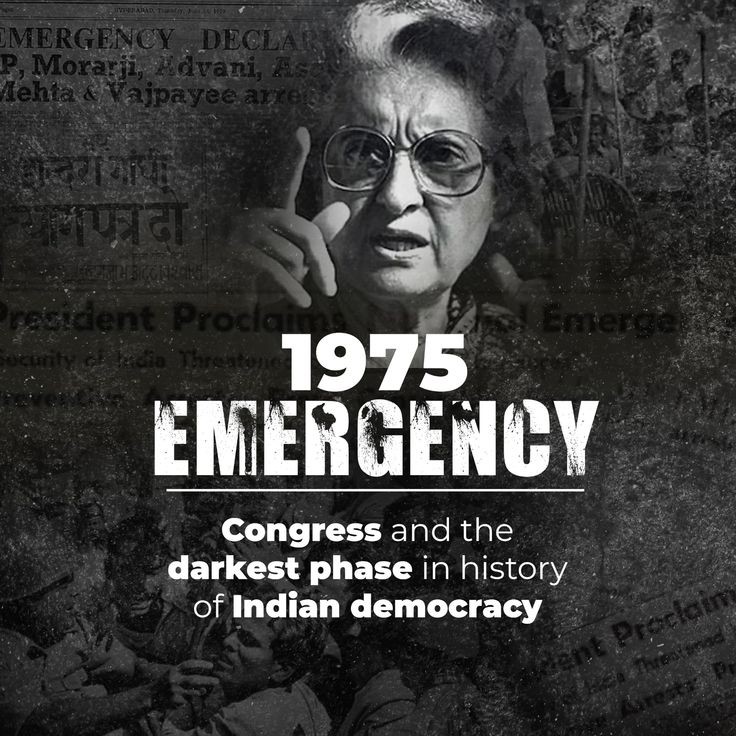

The proclamation of Emergency on June 25, 1975, by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi signified one of the darkest and most contentious periods in Indian democracy. This era prompted fundamental inquiries regarding constitutional morality, the separation of powers, and the resilience of India’s democratic structure.

The Emergency, characterised by numerous observers as a period of suspended democracy, endured for 21 months, during which India experienced the abrogation of civil freedoms, repression of dissent, incarceration of political opponents, and a total concentration of power. This serves as a poignant reminder of the perils associated with unchecked presidential authority and the fragility of democratic institutions.

Socio-Political and Economic Context of 1975

By 1975, India was struggling with several internal crises:

- Economic distress: High inflation, unemployment, food scarcity, and diminishing industrial production have undermined public confidence.

- Political discontent: The 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War significantly enhanced Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s popularity, but corruption, centralised governance, and escalating authoritarianism resulted in growing opposition.

- Student protests: In Gujarat and Bihar, students spearheaded significant rallies against corruption and misgovernance, motivated by socialist leader Jayaprakash Narayan’s call for “Total Revolution.”

- Judicial setback: On June 12, 1975, the Allahabad High Court annulled Indira Gandhi’s 1971 electoral victory due to electoral misconduct under the Representation of People Act.

- Confronted with a probable disqualification from Parliament and intensifying mass protests, Gandhi urged President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed to declare an Emergency under Article 352, referencing “internal disturbance.”

Legal and Constitutional Basis of the Emergency

Article 352: National Emergency

- Article 352 empowers the President to proclaim an Emergency when India’s security is jeopardised by war, external aggression, or internal disturbance.

- In 1975, the rationale was “internal disturbance,” an ambiguous term that permitted broad interpretation and subsequent misuse.

Article 359: Suspension of Fundamental Rights

- The President, pursuant to Article 359, suspended the right to pursue legal remedies for the implementation of Articles 14 (equality before the law), 21 (protection of life and personal liberty), and 22 (protection against arbitrary arrest).

- This proclamation effectively imposed a constitutional lockdown across the whole nation.

Suspension of Civil Liberties and Press Freedom

- More than 100,000 individuals, including opposition leaders such as Atal Bihari Vajpayee, L.K. Advani, Morarji Desai, and George Fernandes, were incarcerated under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) without trial.

- Censorship of the press was instituted; newspapers were mandated to obtain government approval prior to publication.

- Forced sterilisations under Sanjay Gandhi’s population control initiative infringed on bodily liberty.

- Demolitions of slums in Delhi resulted in widespread displacements under the pretext of urban regeneration.

Role of the Judiciary: ADM Jabalpur Case

- The judiciary’s role during the Emergency has been broadly criticised as a failure to uphold the Constitution.

ADM Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla (1976)

- The Supreme Court, in the widely recognised Habeas Corpus decision, determined (by a 4:1 majority) that under the Emergency, the right to life (Article 21) stood suspended.

- Justice H.R. Khanna dissented, contending that the right to life and liberty is inalienable and not solely a constitutional right. He was subsequently replaced in his position as Chief Justice, a decision broadly perceived as punitive.

- Justice Hans Raj Khanna’s dissent in the landmark case ADM Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla (AIR 1976 SC 1207) is regarded as one of the most courageous judicial actions in Indian constitutional history.

- Although the majority contended that the right to life and liberty might be suspended during an Emergency, Justice Khanna dissented, asserting unambiguously that “the Constitution does not contemplate a situation in which there is no remedy to a person even if he is detained arbitrarily.”

- He cautioned that acquiescing to the government’s position would signify the abrogation of the rule of law during the Emergency.

- His dissent, despite resulting in the loss of the Chief Justiceship, emerged as a symbol of judicial independence and moral character.

- Subsequent generations of jurists, intellectuals, and the Supreme Court have acknowledged Khanna’s decision as constitutionally valid and ethically sound.

- His legacy serves as a reminder to India that constitutional principles must be maintained notwithstanding significant administrative coercion

Institutional Degradation and Executive Centralisation

- The Parliament was reduced to a mere rubber stamp, with ordinances supplanting debate and consultation.

- The President acted solely on the Prime Minister’s counsel, so undermining the federal framework.

- The Election Commission and civil servants were compelled into silence or cooperation.

Constitutional Reforms Post-Emergency: Learning from the Past

The 44th Amendment to the Constitution, enacted in 1978

- The Janata government, led by Morarji Desai, implemented essential protections to rectify the distortions of the Emergency.

- The phrase “internal disturbance” was substituted with “armed rebellion” in Article 352.

- Fundamental Rights enshrined in Articles 20 and 21 are non-suspendable, even in times of Emergency.

- An emergency proclamation necessitated formal Cabinet advice and parliamentary approval within one month.

- Provisions for biannual parliamentary approval were instituted.

Emergency and the Strengthening of Fundamental Rights Jurisprudence

- The Emergency paradoxically resulted in a stronger jurisprudence regarding rights in the post-1977 era.

- In Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978), the Court reinterpreted Article 21 to stipulate that the “procedure established by law must be just, fair, and reasonable,” so broadening the scope of liberty.

- The Puttaswamy (Privacy) Judgment (2017) affirmed the right to privacy as a fundamental right and specifically overruled ADM Jabalpur.

- The Court recognised its shortcomings during the Emergency, marking an unusual instance of institutional self-reflection.

The Emergency in Public Memory and Contemporary Significance

Political Symbolism

- The Emergency has evolved into a political symbol of dictatorship.

- It is frequently referenced in political discourse when constitutional principles are deemed to be at risk.

Scrutiny of Authoritarian Tendencies

- Current apprehensions over the abuse of sedition laws, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, surveillance, internet blackouts, and media suppression are framed within the backdrop of the Emergency.

- Civil society and the judiciary have become increasingly proactive in safeguarding democratic liberties following the Emergency.

Education and Civic Competence

- The Emergency serves as a case study in law, political science, and journalism programs in Indian institutions, reminding the younger generation of their democratic obligations and constitutional ethics.

Lessons for Democratic India

- The Emergency of 1975–77 acts as a constitutional trial, evaluating the nation’s dedication to democracy, freedom, and the rule of law.

- Although India reinstated its democratic trajectory with the elections of 1977, the era left an indelible mark and a cautionary tale.

- The Constitution, though robust, is not self-executing; it necessitates institutional integrity, an engaged population, and constitutional ethics to endure political turmoil.

- The post-Emergency reforms and a more aggressive court signify progress; yet, the issues of executive overreach, the loss of human freedoms, and the misuse of state power persist today.

- In reflecting on the Emergency, India must not only denounce the past but also safeguard the present and protect the future of its democracy.

- The Emergency of 1975–77, proclaimed by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, was a pivotal era in Indian democracy.

- The Allahabad High Court’s ruling disqualifying Gandhi for election misconduct resulted in the suspension of civil freedoms, the arrest of political rivals, and stringent censorship. This action was justified under Article 352 as a reaction to “internal disturbances.”

- The era had unparalleled authoritarianism, characterised by mass sterilisations, slum clearances, and media control, with Indira’s son Sanjay Gandhi exercising unofficial authority.

- Resistance persisted through underground movements and opposition figures such as Jayaprakash Narayan.

- The Emergency concluded in 1977 when Gandhi mandated elections, leading to a significant setback for the Congress and the ascendance of the Janata Party.

- The legacy of this era resulted in essential constitutional protections such as the 44th Amendment, which complicates the potential misuse of Emergency powers and serves as a potent reminder of democratic fragility and strength.

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...