Table of Contents

Why in the news?

The Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, has reignited discussions about the Doctrine of Presumption of Constitutionality, a vital legal principle that views laws passed by the legislature as constitutional until proven otherwise. This doctrine reinforces trust in the legislative process, asserting that elected representatives create laws aligned with the Constitution and societal interests.

At its core, the doctrine advocates for judicial restraint, urging courts to uphold laws unless compelling evidence demonstrates a constitutional violation. This minimizes unnecessary judicial intervention and respects the legislature’s role as the voice of the people, requiring substantial evidence for any legal challenge to succeed. It also helps maintain governance stability and ensures continuity in the law.

Additionally, presuming the constitutionality of statutes enables a balance of power among government branches, acknowledging the legislative process’s legitimacy and expertise. This balance safeguards democratic frameworks, allowing laws to be effective while protecting citizens’ rights unless clear evidence against the law emerges.

Waqf (Amendment) Act 2025

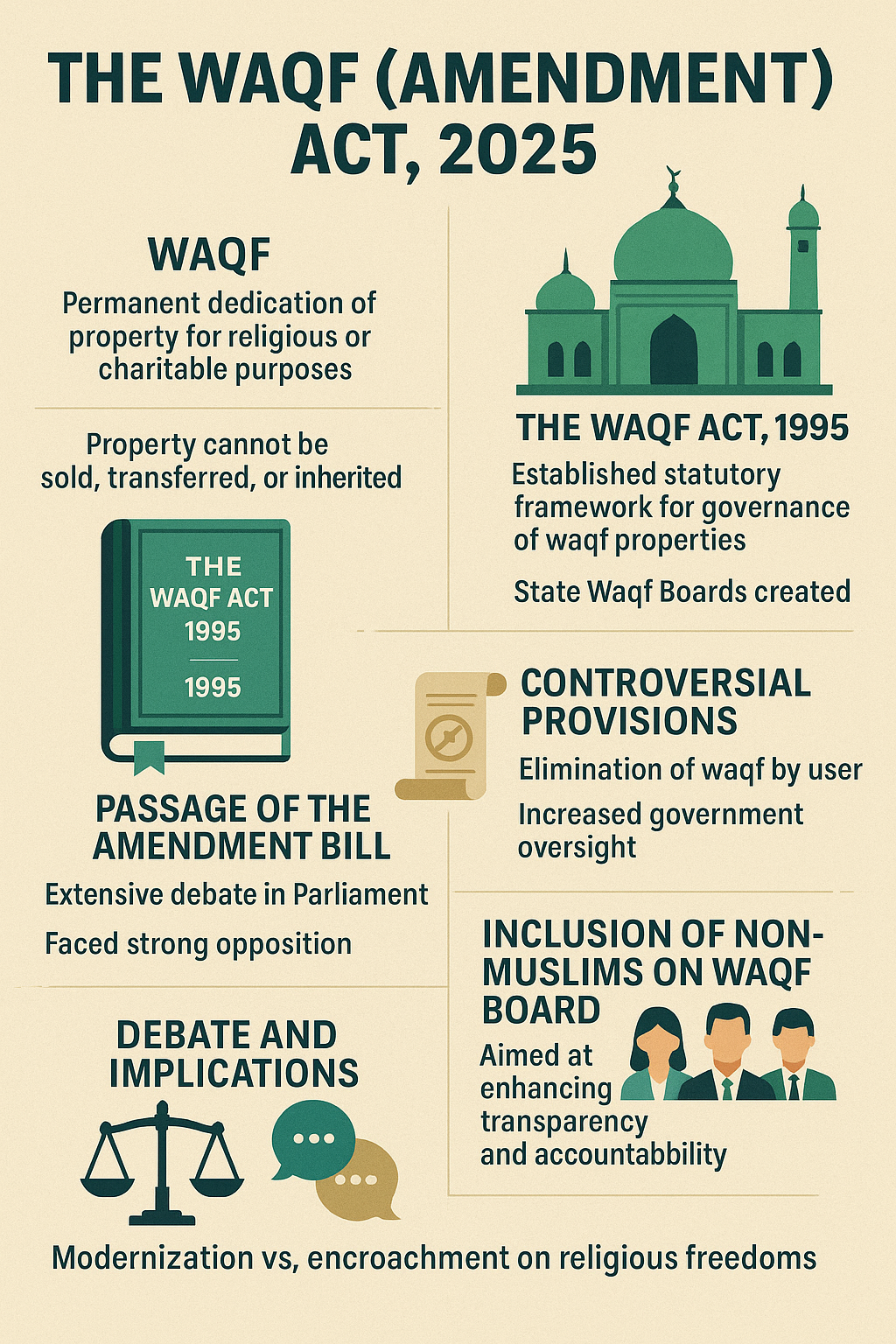

In Islamic jurisprudence, Waqf refers to the permanent dedication of property for religious or charitable purposes in the name of God. Such properties generate income that is typically allocated to maintaining mosques, funding educational institutions, or supporting the underprivileged. A defining characteristic of Waqf is its inalienability; once designated as Waqf, the property cannot be sold, transferred, or inherited. This principle ensures that the asset remains perpetually devoted to its intended religious or social function.

Waqf Act 1995

The Waqf Act, 1995, along with its 2013 amendments introduced by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, established a statutory framework for the governance of Waqf properties. It also led to the creation of State Waqf Boards, which oversee the administration and management of these assets.

Waqf (Amendment) Bill, 2025

On 4 April 2025, Parliament passed the Waqf (Amendment) Bill, 2025, following an extensive debate lasting over 12 hours in the Lok Sabha and 14 hours in the Rajya Sabha. The Bill, which significantly alters the Waqf Act, 1995, faced strong opposition from various political parties. The President granted assent to the Bill on 5 April 2025, officially making it law. Initially introduced in the Lok Sabha on 8 August 2024, the draft legislation proposed renaming the existing Act as the Unified Waqf Management, Empowerment, Efficiency, and Development Act. The Union government described it as a comprehensive reform aimed at enhancing the efficiency of Waqf property administration.

Major Provisions

One of the most controversial provisions in the 2025 Amendment is the elimination of Waqf by user for future Waqf properties. Traditionally, properties used for religious or charitable purposes over time could acquire Waqf status even without formal documentation. The new law removes this recognition, restricting Waqf formation to explicit declarations or endowments. Additionally, the amendment significantly increases government oversight in managing Waqf assets and adjudicating disputes related to them.

Another major change is the mandated inclusion of non-Muslim members on the Waqf Board, a move the government argues will enhance transparency and accountability. However, critics, including opposition leaders and community representatives, argue that these provisions diminish the religious autonomy of the Muslim community. They contend that the Act erodes traditional Waqf governance, potentially marginalising Muslims and reducing their influence over religious endowments. Some opponents have gone as far as to claim that the amendments seek to relegate Muslims to “second-class citizens“, questioning both the intent and implications of the legislation.

The passage of the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, has ignited intense debate, with supporters viewing it as a modernisation effort and detractors perceiving it as an encroachment on religious freedoms. The broader implications of these reforms, particularly in terms of constitutional guarantees and minority rights, continue to be a subject of legal and political scrutiny.

In re: Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025

Following the presidential assent to the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, an unprecedented wave of legal challenges emerged, with over 65 petitions filed before the Supreme Court. These petitions were submitted by a diverse group of politicians, civil rights organisations, and legal advocates, all contesting the Act’s constitutional validity. Among the petitioners were prominent political figures, including Asaduddin Owaisi (AIMIM), Amanatullah Khan (AAP), Imran Masood and Udit Raj (Congress), Manoj Kumar Jha (RJD), Mahua Moitra (TMC), Mohammad Salim (CPI-M), and Syed Kalbe Jawad Naqvi, a Shia cleric. Additionally, organisations such as the Association for the Protection of Civil Rights, Jamiat Ulama-e-Hind, Indian Union Muslim League, Communist Party of India, and Anjuman-E-Islam joined the legal battle.

While opposition to the Act was widespread, six states i.e., Haryana, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, and Assam, supported its constitutionality and formally approached the Supreme Court to defend the legislation.

The Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, has sparked significant controversy, with critics arguing that it infringes upon the rights of the Muslim community. Petitioners contend that the Act permits the government to acquire waqf properties without compensation, a move they claim violates Article 25 of the Constitution, which guarantees freedom of religion. The Act’s provisions have been challenged in the Supreme Court, with opponents asserting that it undermines religious autonomy and disproportionately affects minority rights.

Problematic Sections of Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025

Critics have highlighted several problematic sections of the 2025 Act, particularly Section 3C, which allows encroachers to initiate disputes over waqf properties. This provision has raised concerns that minor disputes could lead to the freezing of waqf status for entire properties, potentially disrupting their religious and charitable functions. Furthermore, the Act lacks a clear timeline for resolving such disputes, creating uncertainty regarding the legal status of waqf assets.

First Hearing

The first hearing took place on 16 April 2025, before a Division Bench led by Chief Justice Sanjiv Khanna, alongside Justices P.V. Sanjay Kumar and K.V. Viswanathan. The Bench reviewed ten petitions challenging the constitutional validity of the 2025 Amendment Act.

Second Hearing

During the second hearing on 17 April, the Union government was granted one week to submit its responses, contingent upon two assurances.

- No waqf properties, including those classified under waqf by user, would be denotified by the Union.

- No new appointments would be made to the Waqf Council or Waqf Board before the next hearing.

Additionally, the Court imposed restrictions on the number of legal representatives, stating that only five counsels from the petitioners’ side would be heard. The case was scheduled for further proceedings in the week commencing 5 May 2025, with the Bench explicitly refusing to entertain any fresh petitions. On 29th April, the Bench reaffirmed its stance, dismissing 25 petitions, including one filed by TMC leader Derek O’Brien, as withdrawn.

On 5th May, Chief Justice Khanna deferred the case to a new Bench, citing his impending retirement as the reason for his inability to conclude the matter. The case was reassigned to CJI-Designate B.R. Gavai. On 15 May, a Bench led by CJI Gavai and Justice A.G. Masih convened for the first time to hear the matter. At this stage, the Bench clarified that it would only consider arguments related to interim relief, postponing a comprehensive review of the Act’s validity. The case was scheduled for further hearings on 20 May.

The petition over the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, continues to unfold, with constitutional principles, religious autonomy, and governance structures at the heart of the debate. The Supreme Court’s rulings in the coming weeks will likely shape the future of waqf administration and its intersection with state authority.

Also Read: Right to Freedom of Religion in India

Doctrine of Presumption of Constitutionality

The Doctrine of Presumption of Constitutionality is a foundational principle in Indian constitutional law that underscores the legislature’s authority in crafting laws that reflect societal needs. It operates on the assumption that laws enacted by Parliament or state legislatures are constitutionally valid unless proven otherwise. This doctrine places the burden of proof on those who challenge a law’s legitimacy, requiring them to demonstrate a clear and unequivocal violation of constitutional provisions.

This doctrine plays a crucial role in maintaining the balance of power between the legislature and judiciary. By presuming the validity of statutes, it prevents excessive judicial intervention in legislative matters, ensuring that courts do not arbitrarily strike down laws without compelling evidence of constitutional breaches. Additionally, it fosters legal stability and predictability, allowing laws to remain effective and enforceable until they are formally declared unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court of India has consistently upheld the Doctrine of Presumption of Constitutionality, emphasising that courts should interpret laws in a manner that supports their validity unless there is manifest arbitrariness or a direct conflict with constitutional provisions. This doctrine is deeply rooted in the separation of powers, ensuring that each branch of government operates within its prescribed constitutional limits. It acknowledges that elected representatives, accountable to the public, are best positioned to address societal needs through legislation. It ensures that laws remain operational and enforceable until conclusively struck down by the judiciary. It prevents undue judicial interference, preserving the delicate balance between legislative and judicial authority.

The Doctrine of Presumption of Constitutionality holds significant legal weight, fundamentally influencing how courts, lawmakers, and litigants engage with the legitimacy of statutes. Below are the primary legal ramifications of this doctrine:

1. Burden of Proof on the Challenger

A key implication of the doctrine is that individuals contesting a law’s constitutionality carry the burden of disproving its validity. Courts do not assume a statute is unconstitutional merely because it is challenged; rather, the challenger must present clear and convincing evidence that demonstrates the law’s violation of constitutional principles. This requirement ensures that legislative measures are not easily annulled.

2. Judicial Restraint

The doctrine fosters judicial restraint, discouraging courts from intervening in legislative matters unless there is evidence of explicit arbitrariness, irrationality, or a direct constitutional infringement. Courts aim to interpret statutes in a manner that upholds their constitutionality, only declaring laws unconstitutional when no reasonable interpretation can support their validity.

3. Legislative Supremacy and Separation of Powers

By assuming statutes are constitutional, the doctrine reinforces the authority of elected legislatures while maintaining the separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. This safeguards against judicial overreach and preserves the legislature’s policymaking role.

4. Stability in Governance and Legal Certainty

The presumption contributes to stability and predictability within governance, allowing laws to remain in force and enforceable until deemed invalid by the courts. This prevents disruptions in legal continuity, ensuring that government operations are not impeded by frequent constitutional challenges.

5. Challenges in Fundamental Rights Litigation

While the doctrine protects legislative autonomy, it can present obstacles for litigation involving fundamental rights. Petitioners asserting that a law violates individual rights must overcome the presumption of constitutionality by showing that the statute imposes unreasonable restrictions or is inherently discriminatory. This is especially pertinent in cases relating to religious freedoms, equality, and personal liberties.

6. Precedential Influence in Constitutional Matters

Indian courts frequently rely on previous rulings that have upheld the doctrine when addressing constitutional disputes. This means that a law’s presumed validity is bolstered through judicial precedent, making it more challenging for later challenges to prevail unless accompanied by new evidence or evolving legal interpretations.

7. Checks and Balances in Government Decision-Making

Although the doctrine supports legislative authority, it operates within a wider system of judicial review. Courts retain the authority to invalidate legislation that contradicts fundamental rights, exceeds legislative competence, or violates constitutional mandates. Therefore, the doctrine does not grant immunity to laws against scrutiny; it ensures that constitutional challenges are grounded in robust legal reasoning.

The Doctrine of Presumption of Constitutionality is vital in upholding legislative authority, ensuring judicial restraint, and preserving legal stability. Nonetheless, its practical application is often a point of legal contention, particularly in scenarios where challengers claim that statutes encroach upon constitutional rights and liberties. The Supreme Court’s decisions continue to shape how this doctrine influences constitutional litigation in India.

While the Doctrine of Presumption of Constitutionality reinforces legislative legitimacy, its application in cases like the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025 highlights the complex interplay between governance, minority rights, and judicial oversight. As legal challenges unfold, the Supreme Court’s rulings will shape the future discourse on constitutional interpretation, particularly in matters concerning religious freedoms and state intervention.

Should the Age of Consent Be Lowered?

Should the Age of Consent Be Lowered?

A Choice Before India: Rule of Law or Ru...

A Choice Before India: Rule of Law or Ru...

The Right to Speedy Trial Under Article ...

The Right to Speedy Trial Under Article ...