Q1-Discuss the ‘corrupt practices’ for the purpose of the Representation of the People Act, 1951. Analyze whether the increase in the assets of the legislators and/or their associates, disproportionate to their known sources of income, would constitute ‘undue influence’ and consequently a corrupt practice.

Approach:

|

Model Answer

To ensure free and fair elections, the RPA, 1951 defines specific acts as “corrupt practices” (mainly under Section 123 of RPA, 1951:

- Bribery: Offering or accepting gratification to influence voting.

- Undue Influence: Interfering with a voter’s free choice through threat, coercion, or spiritual pressure.which criminalizes illicit enrichment by public servants.

- Appeal on Religion, Caste, Community, Language, etc.: Soliciting votes or promoting enmity on these grounds.

- Use of Religious/Clerical Influence: Seeking or giving religious endorsement for votes.

- Publication of False Statements: Circulating lies about a candidate’s personal character or withdrawal.

- Free Conveyance of Voters: Providing vehicles or transport to voters unlawfully.

- Exceeding Expenditure Limit: Spending beyond the legal ceiling in elections.

- Use of Government Servants: Employing officials or state machinery for campaigning.

- Booth Capturing: Seizing polling stations, ballot boxes, or EVMs by force or intimidation.

- Misuse of Official Position: Using ministerial authority, schemes, or government resources to influence voters.

Implications of Corrupt Practices under RPA, 1951 (with Case Laws)

- Election declared void: Guilty candidate’s election can be annulled by the High Court (Sec. 100, RPA); upheld in Indira Nehru Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975).

- Disqualification up to 6 years: Candidate may be barred on EC’s opinion to the President.

- Criminal liability: Practices like bribery, undue influence, or booth capturing attract imprisonment/fine.

- Loss of democratic mandate: Election results stand nullified if secured by malpractice; Indira Gandhi case (1975) declared free & fair elections part of the Basic Structure.

- Deterrence against misuse of power: Harsh consequences prevent money power, muscle power, or abuse of office on election expenditure.

- Integrity of voter rights: Voters’ free will safeguarded from inducement or intimidation; strict standards against undue influence.

- Judicial oversight: Election petitions under Sec. 80/81 RPA fall within High Court jurisdiction, ensuring scrutiny

- Ban on communal/sectarian appeals: Appeals to religion, caste, or language as a corrupt practice).

Part – II

Increase in disproportionate assets (DA) of legislators or their associates is primarily criminalised under Sec. 13(1)(e), Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (PCA). The Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RPA), under Sec. 123, defines corrupt practices but does not explicitly include DA. The debate emerges when such enrichment is concealed or misused during elections.

Arguments Against DA as Corrupt Practice

- Statutory Separation – PCA addresses corruption, RPA addresses electoral malpractice.

- No Automatic Nexus – Wealth increase alone does not directly interfere with voter choice.

- Risk of Overreach – Expanding RPA to cover all DA cases dilutes its electoral focus.

Arguments For DA as Corrupt Practice

- Concealment in Affidavits (Sec. 33A, 75A RPA):

- PUCL v. Union of India (2003): Right to know = Art. 19(1)(a).

- Krishnamoorthy v. Sivakumar (2015): Nondisclosure = undue influence.

- Lok Prahari v. Union of India (2018): legislators must disclose not only their assets but also those of their spouses and dependents, including any increase during their tenure.

- Electoral Misuse: DA wealth for bribery/inducements → Sec. 123(1); excess expenditure → Sec. 123(6).

- Level Playing Field: Unexplained enrichment undermines fairness, disadvantaged honest candidates.

- Ethical Dimension: DA erodes public trust and fosters cynicism about politics as a means of enrichment.

- Current Relevance: Convictions like K. Ponmudy (2023) and Rukmini Madegowda (2022) show judicial scrutiny of DA and nondisclosure.

- Comparative Insight: Democracies such as the US and UK enforce strict asset audits and independent monitoring.

Law Commission Recommendations (255th Report)

- Treat false affidavits/unexplained enrichment as corrupt practices, mandate annual disclosures, and enable IT cross-verification.

- DA growth per se is a PCA offence, not undue influence. But concealment in affidavits or electoral misuse transforms it into a corrupt practice under Sec. 123 RPA. Recognising informational manipulation alongside monetary bribery is vital to protect electoral integrity and democratic legitimacy.

Lok Prahari case makes clear that while DA increase per se is a PCA offence, its concealment or electoral misuse amounts to undue influence and therefore a corrupt practice under RPA, 1951. Thus, transparency in assets is indispensable to safeguard voter autonomy and electoral integrity.

UPSC Final Result 2025 Soon: Check CSE M...

UPSC Final Result 2025 Soon: Check CSE M...

UPSC Correction Window 2026: Dates, Dire...

UPSC Correction Window 2026: Dates, Dire...

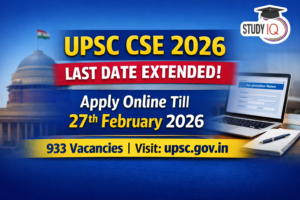

UPSC CSE 2026 Last Date Extended to 27 F...

UPSC CSE 2026 Last Date Extended to 27 F...