Table of Contents

The denial of bail in situations about the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA) underscores the conflict between national security and personal freedom. The recent ruling by the Delhi High Court denying bail to nine accused persons, including student activist Umar Khalid, in the 2020 Delhi riots case, highlights how the rigorous bail conditions under the UAPA compromise constitutional guarantees of liberty and due process. The premise of criminal jurisprudence, stating that an individual is “innocent until proven guilty“, is undermined, and the norm that “bail is the rule and jail the exception” is inverted.

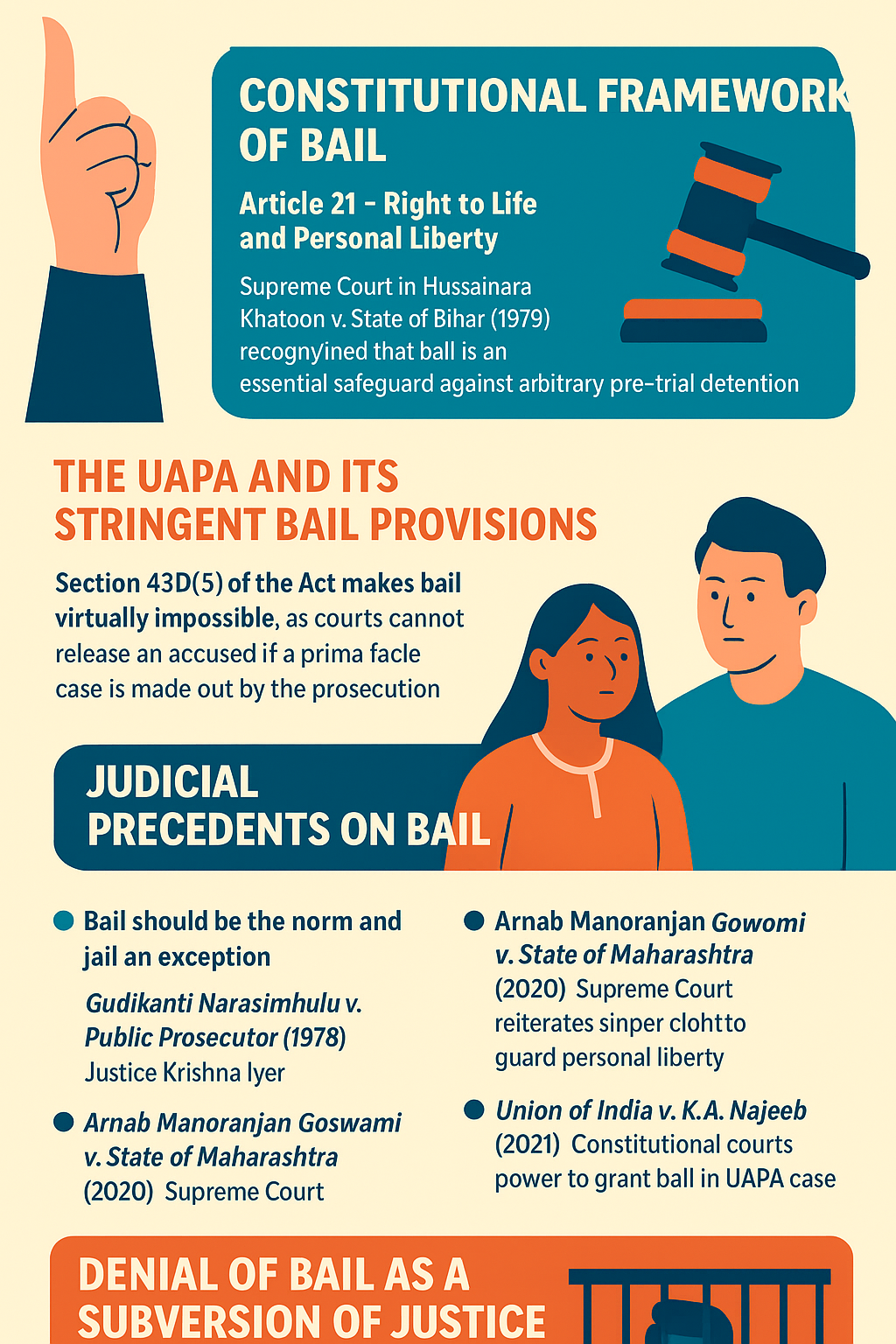

The Constitutional Framework of Bail

Article 21 – Right to Life and Personal Liberty

- The right to bail derives from the guarantee of personal liberty as stipulated in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution.

- The Supreme Court in Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar (1979) acknowledged that bail serves as a crucial protection against capricious pre-trial detention, particularly for undertrials.

Article 14 – Equal Treatment Under the Law

- Discretion in bail determinations must adhere to the equality principle outlined in Article 14, guaranteeing justice and the absence of discrimination.

- The implementation of UAPA creates inequity by placing a substantial burden on the accused to refute prima facie guilt before securing bail.

Key Provisions of the UAPA

- Objective: Empowers the government to counteract activities that jeopardise the sovereignty, integrity, and security of India.

- Prohibited Organisation: The government has the authority to designate any organisation as “unlawful,” however, this determination is subject to judicial review.

- Act of Terrorism: Any action that jeopardises India’s unity, security, or economy, or aims to instil terror in individuals (inside India or internationally) is classified as a terrorist act.

- Terrorist Group. The government may designate a group of individuals involved in illicit operations as a terrorist organisation.

- Terrorist Organisation: Denotes organisations specified in the UAPA Schedule or any entity operating under the same designation.

- Custody of the Accused: An accused individual may be detained without a charge sheet for a maximum of 180 days (6 months).

- Grant of Bail: Section 43D(5): Bail may be refused if the court determines that there exists a “prima facie” case against the accused.

- Economic offence: Actions jeopardising India’s economic security are classified as terrorist activities to comply with FATF requirements.

- Individuals as Perpetrators of Terrorism: In 2019, individuals, in addition to organisations, can be designated as terrorists.

- Seizure of Property: The Director-General of the NIA has the authority to authorise the seizure or attachment of property associated with a case.

The UAPA and Its Rigorous Bail Provisions

The UAPA has become an instrument conferring extensive authority to the State.

- Section 43D(5) of the Act renders bail nearly unattainable, as courts are prohibited from releasing an accused if the prosecution establishes a prima facie case. This shifts the burden of proof and establishes a presumption of guilt at the bail stage.

- The Supreme Court in National Investigation Agency v. Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali (2019) reaffirmed this stringent criterion, determining that courts must regard the prosecution’s account as credible while adjudicating bail. This ruling has adversely impacted personal liberty by constraining judicial discretion.

Judicial Precedents Regarding Bail

- In Gudikanti Narasimhulu v. Public Prosecutor (1978), Justice Krishna Iyer asserted that bail ought to be the standard, while imprisonment should be the exception, highlighting the human rights aspect of pre-trial freedom.

- Arnab Manoranjan Goswami v. State of Maharashtra (2020): The Supreme Court emphasised that liberty cannot be forfeited on ambiguous grounds, and the court must diligently protect human liberty.

- Union of India v. K.A. Najeeb (2021): The Court determined that constitutional courts possess the authority to issue bail in UAPA cases involving undertrials subjected to extended detention, notwithstanding statutory limitations.

- Shaheen Welfare Association v. Union of India (1996): The Court emphasised that the persistent refusal of bail to undertrials experiencing excessive trial delays would contravene Article 21 in the context of TADA.

- These precedents illustrate a constitutional equilibrium between the State’s interest in security and the individual’s right to freedom.

Denial of Bail as an Erosion of Justice

The Delhi High Court’s refusal to grant bail in the Delhi riots UAPA case underscores systemic problems.

- Presumptions of guilt during the bail phase: Courts frequently depend on the prosecution’s argument without further examination.

- Extended trials – In instances where trials extend for years, the denial of bail effectively constitutes punishment without a conviction.

- The chilling impact on dissent – The application of UAPA against activists, students, and journalists indicates a pattern of stifling dissent under the pretext of national security.

- Such acts diminish the integrity of the legal system, undermining trust in constitutional protections.

Bail Jurisprudence in the International Context

International Human Rights Standards

- Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which India is a signatory, stipulates that “it shall not be the general rule that individuals awaiting trial shall be held in custody.”

- The UN Human Rights Committee has consistently maintained that extended pre-trial imprisonment infringes upon the presumption of innocence.

- In A. v. United Kingdom (2009, ECHR), the European Court of Human Rights determined that prolonged imprisonment without trial necessitates sufficient justification.

- The existing bail framework in India under the UAPA contradicts international standards, prompting significant concerns regarding its adherence to global human rights commitments.

Path Ahead: Reestablishing Equilibrium

- Judicial Scrutiny – Courts are required to apply rigorous scrutiny throughout the bail phase, safeguarding liberty against the potential harm of ambiguous accusations.

- Legislative Reform – Parliament must reassess Section 43D(5) of the UAPA to ensure its conformity with constitutional protections and international standards.

- Time-Limited Trials – Extended detention without trial contravenes Article 21. The expedited processing of UAPA trials is crucial.

- The Proportionality Doctrine, as established in Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017), mandates that limitations on fundamental rights must be reasonable. The bail requirements of the UAPA must be evaluated against this fundamental notion.

Conclusion

- The denial of bail under the UAPA constitutes a serious undermining of justice, transforming incarceration into the standard and liberty into the anomaly.

- The Delhi High Court’s ruling illustrates the overarching dilemma of liberty within India’s criminal justice system.

- Bail is not a privilege but a fundamental protection enshrined in Articles 14 and 21, and courts must guarantee that preventative detention does not devolve into punitive imprisonment.

- A democracy founded on the rule of law must assert that the restriction of liberty should consistently be the exception rather than the norm.

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Trial by Social Media: Public Shaming, D...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Governors’ Address to State Legislatur...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...

Mandating Prior Approval for Corruption ...