Table of Contents

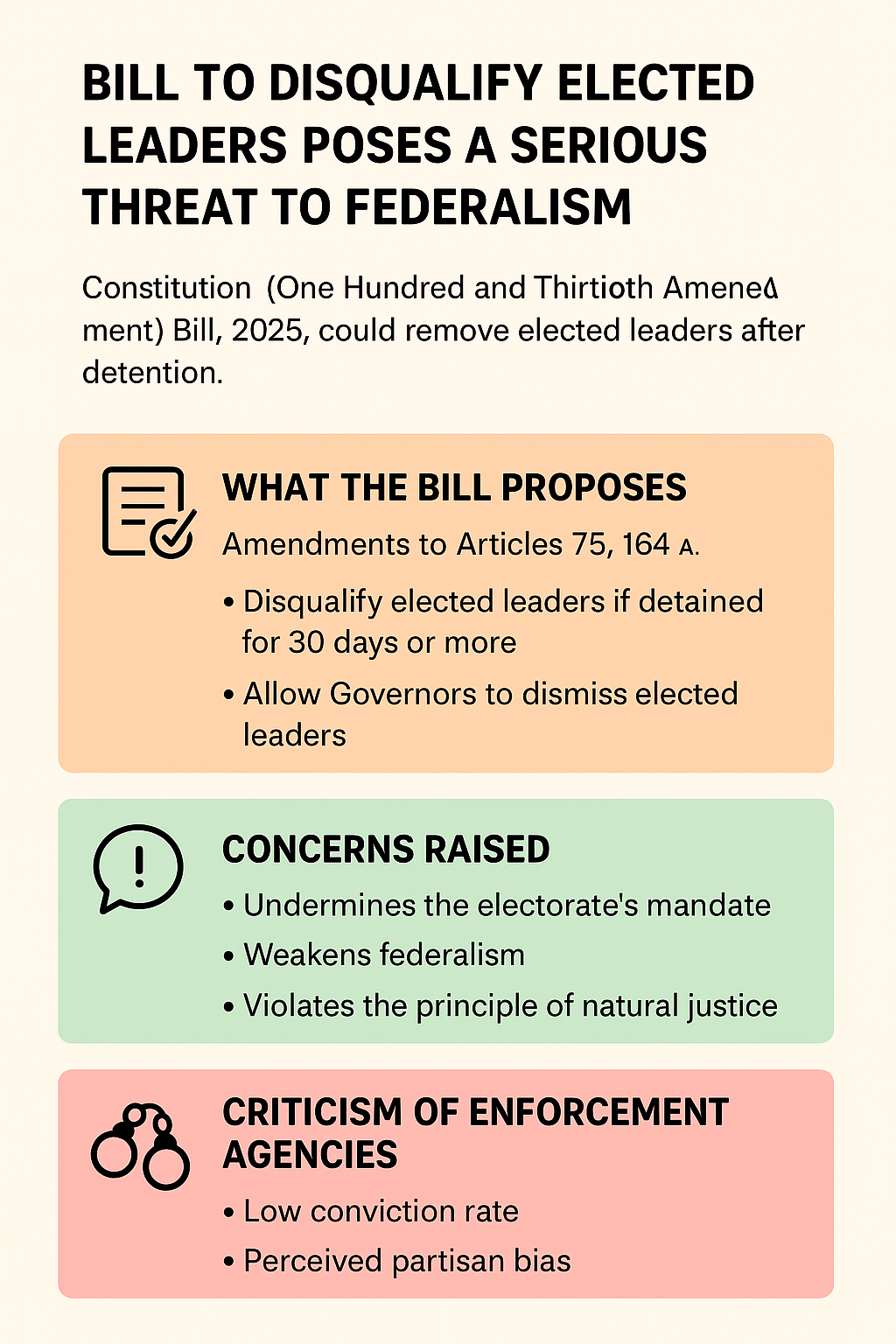

The Constitution (One Hundred and Thirtieth Amendment) Bill, 2025, presented in the Lok Sabha on August 20, 2025, by Union Home Minister Amit Shah, aims to disqualify elected representatives, including the Prime Minister and Chief Ministers, if they are incarcerated for 30 days or longer on serious criminal charges. The present government has defended the Bill as a measure to enhance constitutional morals and eradicate corruption; yet, it has elicited significant apprehensions over its impact on democracy, federalism, and the notion of natural justice.

Principal Provisions of the Bill to Disqualify Elected Leaders

- The Bill suggests amendments to Articles 75, 164, and 239AA of the Constitution to disqualify elected officials in the event of detention.

- The proposed measure would enable Governors or the President (Union appointees) to remove elected leaders purely based on incarceration, prior to any conviction.

- The removal of Chief Ministers, as heads of elected state governments, might lead to the dissolution of entire Cabinets, so facilitating the imposition of President’s Rule.

Opposition and Criticism

- The Bill has incited significant resistance across political factions. Allies of the ruling BJP, including the Telugu Desam Party, have expressed misgivings. Critics contend that:

- It undermines the public mandate, as leaders are elected by citizens and serve in office based on parliamentary confidence.

- The Bill is susceptible to misuse owing to the absence of accountability in investigating bodies such as the Enforcement Directorate (ED) and the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI).

- The credibility crisis of these bodies, underscored by the Supreme Court on several occasions, engenders scepticism that the Bill is primarily concerned with corruption rather than undermining federalism and suppressing dissent.

The Credibility Crisis of Investigative Agencies

- The Enforcement Directorate has encountered significant judicial criticism. Chief Justice B.R. Gavai (May 22, 2025) remarked that the ED had “exceeded all boundaries” and was undermining federalism.

- Justice Surya Kant stated on August 7, 2025, that the ED were “behaving like crooks.”

Statistics further underscore this crisis

- From 2014 to 2024, the Enforcement Directorate initiated 193 cases against politicians, although only two culminated in convictions, yielding a conviction rate of 1%.

- Nearly all prosecutions were initiated against Opposition leaders, indicating partisan exploitation.

- Conversely, statistics from the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) indicate that 31% of Lok Sabha MPs in 2024 faced significant criminal charges, including many members from the ruling party.

- The disparity between prosecution trends and conviction rates raises concerns about the fairness of the institutions executing these laws.

Constitutional Issues: Federalism and the Fundamental Framework

The Bill directly contests India’s federal structure:

- Article 1 designates India as a “Union of States,” acknowledging the variety and autonomy of its constituent states.

- The Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) case established the basic structure doctrine, asserting that federalism cannot be altered by Parliament.

- The R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994) ruling affirmed that federalism and democratic governance constitute integral components of the basic structure.

- Permitting a Governor, an appointed Union official lacking electoral legitimacy, to remove elected officials compromises these constitutional protections. It circumvents Article 356, which rigorously governs the enforcement of President’s Rule.

Implications for Democracy and the Judiciary

The Bill undermines fundamental democratic principles:

- The presumption of innocence is a fundamental tenet of criminal law, asserting that an accused individual is deemed innocent until proven guilty. Disqualification due to detention contravenes this principle.

- Natural justice: The denial of office without trial infringes upon the right to a fair hearing.

- Protracted judicial proceedings: With 70% of India’s incarcerated individuals being undertrials and conviction rates in political cases falling below 5%, imprisonment does not signify guilt.

- The backlog in India’s judiciary exacerbates the issue.

- More than 50 million cases are still unresolved across the nation.

- The ratio of judges to population is 21 per million, in contrast to 150 in the United States.

- Criminal trials may endure for decades, with some extending beyond 50 years.

- Consequently, the resolution to corruption resides not in disqualification without due process, but in enhancing judicial capability via an increase in judges, digitisation, and systemic reforms.

Enhanced Democratic Framework

- Critics of the Bill highlight its intrinsic contradiction: it aims to maintain constitutional morality, yet numerous members of the ruling party and Cabinet are confronted with significant criminal allegations.

- In Prime Minister Modi’s third Cabinet, 28 out of 71 members are implicated in criminal cases, including serious allegations such as attempted murder and offences against women.

- Should the administration genuinely seek to purify politics, its primary focus must be on expeditious trials and transparency in candidate selection, rather than on measures that may suppress Opposition views under the pretext of legal imprisonment.

Position in the International Sphere

- Worldwide, democracies maintain that incarceration alone does not warrant disqualification. For example:

- In the United Kingdom, Members of Parliament are disqualified solely upon conviction and sentencing to a term exceeding one year in prison.

- In the United States, elected officials retain their positions unless impeached through due process or convicted of grave offences.

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), of which India is a signatory, safeguards the right to political participation (Article 25), limited solely by restrictions that are “reasonable and proportionate.”

- If implemented, the Bill would position India outside the democratic consensus, heightening apprehensions on the deterioration of constitutionalism and international obligations to human rights and democracy.

Conclusion

- The Constitution (One Hundred and Thirtieth Amendment) Bill, 2025, may be portrayed as a mechanism to combat corruption; nonetheless, its provisions jeopardise federalism, democracy, and natural justice.

- Empowering unelected Governors to remove elected officials based only on detention jeopardises the people’s mandate and facilitates partisan use of investigative agencies.

- The true path to ethical politics is found not in hasty disqualifications but in judicial reform, expedited trials, and the responsibility of investigative agencies.

- Protecting federalism and democratic values is crucial for maintaining India’s constitutional identity.

Warring Couples Cannot Make Courts Their...

Warring Couples Cannot Make Courts Their...

Tackling Child Trafficking in India: Leg...

Tackling Child Trafficking in India: Leg...

In Overcrowded Prisons, Justice Has Lost...

In Overcrowded Prisons, Justice Has Lost...